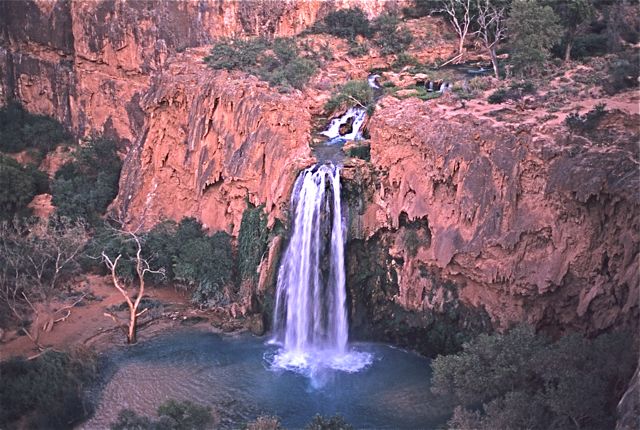

Of all the human groups with ties to the Grand Canyon, the Havasupais have the most enduring and unique relationship to this natural wonder. For centuries the Havasupais have lived along the Grand Canyon’s South Rim, planting crops and tending their orchards in Havasu Canyon (sometimes called Cataract Canyon) and other places within the Grand Canyon during the summer and foraging for game and other resources along the rim and plateau in the winter. The people refer to themselves as Havasu ’Baaja, which has been anglicized into Havasupai. The words mean “people of the blue-green waters,” a name that comes from the clear, beautiful mineral-rich pools of water that gather at the base of spectacular waterfalls along Havasu Creek, their canyon home, which can be reached by the Havasu Canyon Trail.

The Havasupais tell that when their ancestors first saw Havasu Canyon, the people believed that if they entered it the walls would close up and they would be crushed. There are several variations to the rest of the story, but generally a man or several boys use a log to jam it open so the people could enter the canyon safely.

Anthropologists believe that the Havasupais have occupied the canyon for at least 800 years. Over these centuries, the Havasupais have cultivated a close relationship to the natural environment in their canyon home. The Havasupais left their mark on the landscape of the Grand Canyon by utilizing many paths that today have been converted into hiking trails, and by establishing communities at sites such as Indian Garden.

Each layer of the Canyon represents different seasons and different uses of the rocks to the Havasupais. In particular the red rocks are used in Havasupai celebrations and ceremonies as paints. They feel that when they “wear” these rocks, it reaffirms their connection to the Grand Canyon. It also protects their skin from the sun and weather.

The Havasupais tell stories of the stones that they believe protect their canyon home. Two red pillars, known to the Havasupais as Wigleeva, are believed to guard the tribe. Havasupai legends state that if these pillars ever fall, the canyon walls will close in and destroy the people. Across the canyon, directly above the village, are two other rock formations resembling a man carrying a child and a woman. Havasupai stories tell that long ago, when there were too many members to be supported by the canyon’s resources, the tribe split in two. One group decided to move away, but as they were leaving the canyon a man and woman grew sad and turned to look at their canyon home one more time, only to be turned to stone.

Though for centuries the Havasupais traveled wherever they pleased around the Grand Canyon, the arrival of Europeans and Euro-Americans brought important changes. The Spanish, and later Mexicans, claimed control of lands that included the Grand Canyon area; the United States acquired these lands under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. President Rutherford Hayes established the Havasupai Reservation in 1880 on land bordering Havasu Creek. The reservation was reduced to only 500 acres a few years later, confining the tribe to the lands at the base of Havasu Canyon.

This was a major blow to the tribe, since their traditional lifestyle depended on seasonal movements between the canyon floor and plateau uplands. In the fall and winter they would move to the plateau to tend livestock, hunt, and gather food resources, while in the spring and summer they would tend crops and orchards at the bottom of the canyon. Being confined to the bottom of the canyon not only restricted their subsistence and economic opportunities, but it also put increasing pressures on the canyon’s agricultural lands, especially as the population of the tribe grew.

Euro-American influence has disrupted the tribal culture and land use in unexpected ways. For example, the site of the modern campground near Havasu Falls historically was used for Havasupai cremations. Upon a tribal member’s death, others would cremate the body, burn the deceased’s personal belongings, and chop down his fruit trees. After missionaries converted the tribe to Christianity, and with the urging of Bureau of Indian Affairs officials, the Havasupais began burying their dead instead, further reducing their land resources.

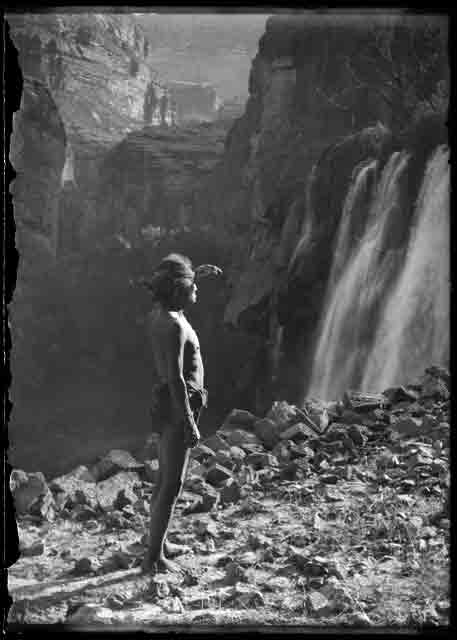

Thilwisa, a Havasupai known to Euro-Americans as “Captain Burro,” befriended William Wallace Bass and showed him many parts of the Grand Canyon. Photo taken at Bridal Veil Falls, today known as Havasu Falls, on the Havasupai Reservation sometime between 1907-1913.

Photo: NAU.PH.568.6289 Kolb Bros. Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

In the 1880s William Wallace Bass was one of the first Euro-Americans to settle near the Havasupais. He befriended members of the tribe who showed him important water sources and introduced him to trails in the canyon that he later developed for his mining and tourism businesses. He often led tourist groups down the Havasu Canyon Trail to visit the tribe and enjoy the spectacular scenery. Later, the Fred Harvey Company and other local tourism businesses would lead similar tours.

The federal government managed most of the lands surrounding the reservation, and when Grand Canyon National Park was created in 1919, it completely encircled the reservation, though the reservation and trails leading down to it were not under NPS control. An amendment to the park’s organic act explicitly allowed the Havasupais to use park lands for traditional purposes, though in practice NPS officials tended to restrict their movement and use of the land. At various times concessionaires and park service officials even proposed developments within Havasu Canyon, including a tourist facility on the canyon floor and a dam on Havasu Creek between its waterfalls. All of these proposals came to naught.

Many Havasupais have worked at the South Rim of Grand Canyon National Park since its inception, living in a small settlement camp near Grand Canyon Village. Some worked as wage laborers for the Santa Fe Railroad or Fred Harvey Company. Others worked for the National Park Service, such as the group of young Havasupai men who carried massive wire cables down the South Kaibab Trail to complete the Kaibab Suspension (or Black) Bridge. More recently some Havasupais have been hired as interpreters for the NPS.

Havasupais lobbied for years for restoration of their plateau lands and a larger voice in how these lands were used by the NPS and tourists. They even fought off a proposal by Grand Canyon Superintendent John McLaughlin to take over the reservation entirely in the 1950s. Finally, in 1975 Congress passed the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act, which returned 185,000 acres of historic tribal plateau lands to Havasupai control and designated an additional 95,000 acres in the park as areas where Havasupais may practice traditional subsistence and ceremonial activities. The tribe and the park service cooperate in regulating use on these 95,000 acres. Disagreements are common as the two seek to accommodate each other’s values and priorities and overcome the history of dispossession that remains such a vivid memory for many Havasupais.

The remoteness of their canyon home has kept this group of Native Americans fairly isolated and their land relatively untrammeled, both for better and for worse. Many brochures advertise Havasu Canyon as an American “Shangri-La,” paradise, or “Eden.”

This map, from the Havasupai Tribe Web site, shows the expanded Havasupai Reservation (in green) created in 1975 by the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act. It lies directly adjacent to the National Park and the Hualapai Indian Reservation.

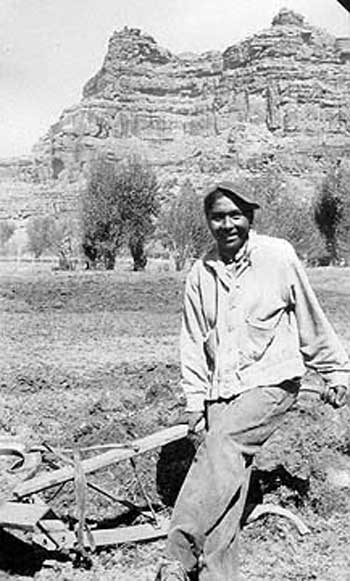

A Havasupai man sits on a plow in Havasu Canyon in 1931. Agriculture was an important part of the Havasupai way of life for centuries, though now tourism is taking over in economic importance—and raising new issues for the tribe.

Photo: NAU.PH.98.7.54. Madge Knobloch Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

Many Havasupais are happy that they have been able to maintain some of their traditions and avoid outside influences, and celebrate their beautiful surroundings. However, there are also problems that come with living here. It is hard for children to get adequate schooling, and access to healthcare is poor. As the tribe grows, there is not enough land in the canyon to provide for everyone.

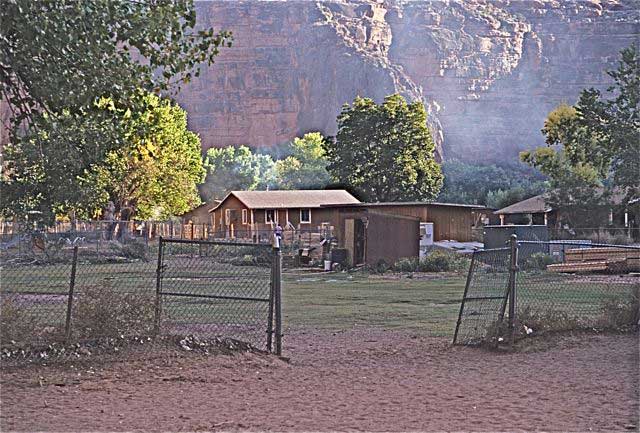

The tribe today consists of approximately 650 enrolled members, with about 450 living at the village of Supai. Limited economic opportunities and a shortage of arable land motivated the tribe to develop its own tourism enterprise. Supai boasts a tribal-run tourism office, café, lodge, and general store, and many families have businesses packing supplies and leading tourists in and out of the canyon. Visitors are required to register ahead of time and pay entrance and environmental care fees to help keep the canyon clean and protected. Backpackers also pay fees to stay at the campgrounds near the waterfalls. Even though tourism is now the lynchpin of the Supai Village economy, the tribe limits the number of visitors who can be in the canyon at any given time.

Life in Havasu Canyon is an accommodation with nature. There are no roads into Supai Village. All access is by foot, mule, or, more recently, helicopter. The pace of life is slow here. The desert air is saturated with the pungent aroma of cottonwoods and willows that thrive in the wet soil of the canyon floor. Havasu Creek flows year round creating a verdant oasis in an otherwise parched land.

Yet, while the creek brings life, it can also bring destruction. Every few decades, heavy rains bring raging floods that cause much property destruction. The canyon bottom is only a few hundred yards wide in most places and these epic floods fill it from cliff base to cliff base. As a consequence, residents hesitate to invest in much infrastructure, preferring simple construction in anticipation of the next flood. In August 2008, a heavy summer downpour breached an old earthen dam far upstream of Supai bringing a torrent of water and debris tearing through the village and campgrounds. It decimated tourism in the canyon for the season. Government flood assistance along with a generous $1 million grant from the California-based San Manuel Band of Serrano Mission Indians in fall 2008 will support an economic recovery plan for the Havasupai in 2009-10.

Tourism can be a mixed blessing. While it stimulates economic development for the remote tribe, it also constantly brings more outsiders in, which means more trash, less privacy, and questions of how to balance it all. The Havasupais draw their identity from the sacred blue-green water that flows through their homeland and through each of them; if it was to become polluted or overtaken by tourists, what would happen to the tribe? It is a question that the Havasupais will have to grapple with as thousands of tourists continue to visit each year.

More information on the Havasupai can be found at their tribal website.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke and Paul Hirt

References:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Dobyns, Henry F. and Robert C. Euler. The Havasupai People. Phoenix: Indian Tribal Series, 1971.

- Havasu ‘Baaja: People of the Blue Green Water. DVD. Havasu ‘Baaja L.L.C., 2004.

- Hirst, Stephen. I Am the Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People. 3rd ed. Grand Canyon Association, 2007.

- Iliff, Flora Gregg. People of the Blue Water: My Adventures Among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians. New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1954.

- Morehouse, Barbara J. A Place Called Grand Canyon: Contested Geographies. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996

- Shields, Kenneth Jr. The Grand Canyon: Native People and Early Visitors. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

- Smithson, Carma Lee and Robert C. Euler. Havasupai Legends: Religion and Mythology of the Havasupai Indians of the Grand Canyon. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994.

- Thybony, Scott. Grand Canyon Trail Guide: Havasu. Grand Canyon Association, 1996.