The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) arrived at Grand Canyon’s North Rim in May 1933. Park administrators soon after directed Company 818 to establish a winter camp (labeled Camp NP-3-A) just below Phantom Ranch at the site of today’s Bright Angel Campground. Their primary inner-canyon mission was to build trails to complete the park’s central trail corridor, and to maintain the lower portions of the South Kaibab and North Kaibab Trails, which had been built by the Park Service during 1922-1928. From October to May in the years 1933 through 1936, as many as two hundred young men labored under the desert sun to fulfill that mission by building the Colorado River (1936), Upper Ribbon Falls (1934), and Clear Creek (1935) Trails.

For several years prior to arrival of the CCC, Park Superintendent Miner Tillotson and Park Engineer C.M. Carrell had considered building a trail from the North Kaibab over to Clear Creek Canyon (the next side canyon east of Bright Angel Creek Canyon) in order to provide additional recreation for guests at Phantom Ranch. The cost of such a project—roughly $50,000 in 1930s dollars—seemed prohibitive, however, as the nation plumbed the depths of the Great Depression. Still, they had laid their plans for this and other inner-canyon trails by the time Franklin Roosevelt embarked on his New Deal jobs creation programs in March 1933. In today’s parlance of economic stimulus programs, the projects were “shovel ready” when the New Deal reached Grand Canyon, so there were no delays in getting the CCC boys down to work.

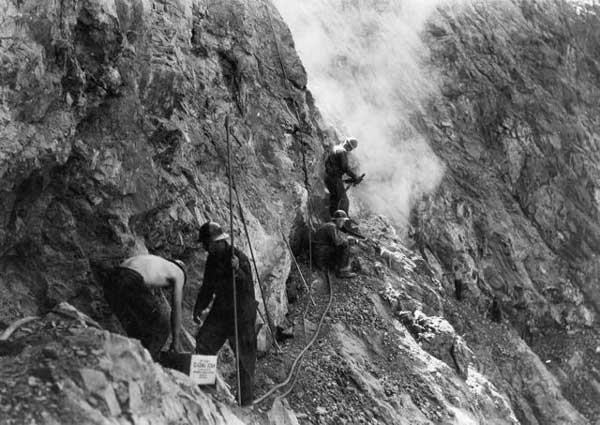

While the majority of Company 818 recruits worked on the difficult Colorado River Trail, and still more were diverted to the Upper Ribbon Falls Trail, CCC foreman Guy Semple and 15 enrollees started up the forbidding schist cliffs of Bright Angel Canyon from the North Kaibab Trail, about a mile north of Phantom Ranch, in the winter of 1933-1934. To reach the Tonto Platform nearly 1,500 vertical feet above Bright Angel Creek, and in the following winter to descend again to the bottom of Clear Creek Canyon, the men used portable compressors, hydraulic drills, hundreds of drill bits, plenty of mules, a ton of sweat, and 10,000 pounds of blasting powder. Semple’s crew finished five miles of trail that first winter. The following year, foremen Lloyd Davis and Harry Moulton returned with 40 men to finish the trail in April 1935.

It was common Park Service practice to stock trout in Grand Canyon’s perennial side streams in the years 1919-1964, then to boast of the excellent fishing to be found at Grand Canyon. True to form, as soon as the trail was completed, rangers stocked Clear Creek with rainbow trout, and the Fred Harvey Company began to offer mule trips from Phantom Ranch for the “excellent trout fishing” as well as visits to the pueblo ruins beside the creek. It seems that concern over the introduction of exotic wildlife species and preservation of cultural resources were not high priorities in the 1930s. In fact, when one of the CCC recruits found several willow branch figurines in a cave beside Clear Creek in December 1933 (the first split-twig figurines found within Grand Canyon), he stuck them in his pocket to send home to his family as souvenirs. Fortunately, he first showed them to his foreman, who sent them up to park naturalist Eddie McKee at the South Rim. They were later carbon dated to 4,500 years old, among the oldest artifacts other than projectile points ever found at Grand Canyon.

The excellent trout fishing at Clear Creek ended when flash floods repeatedly flushed the trout to their deaths in the Colorado River. The Park Service did not continue its stocking efforts at Clear Creek after the 1930s. Fred Harvey’s mule trips ended not too long afterwards and the Clear Creek Trail never did gain the popularity Superintendent Tillotson had imagined. No record has been found that it was ever maintained once the CCC left the inner canyon in the late 1930s, but by the 1960s, backpackers had rediscovered the nine-mile long trail with its CCC features in remarkably good condition. Today it is favored as a central corridor hike by those who want to camp in virtual isolation along an inner canyon creek and to explore from the base of the Redwall Limestone down to the Colorado River.

Hiking the entire nine-mile trail then returning in a day hike is not recommended. Instead, hike about a mile up from Phantom Ranch and turn onto the trail at the small rustic sign. It takes no more than half an hour from that point to reach the Phantom Ranch overlook—a natural platform roughly 250 vertical feet above the ranch with great views and a well-preserved stone bench built by the CCC.

You can continue from there along the hard-won trail blasted through the schist up to the Tonto Platform, perhaps 1,500 vertical feet above the Colorado River. Panoramic views are at their best here, and there is little reason to continue farther east if you have only the day. A backpacking trip from Phantom should allow a full day to reach the informal camp beside Clear Creek. There is no reliable water along the entire route, but once on the Tonto Platform the trail remains reasonably level all the way to the short descent to the creek bottom. Allow at least a day to explore the creek and side canyons before your return.

Written By Michael F. Anderson

References:

- Purvis, Louis Lester. The Ace in the Hole: A Brief History of Company 818 of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Columbus, GA.: Brentwood Christian Press, 1989.

- Anderson, Michael F. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.