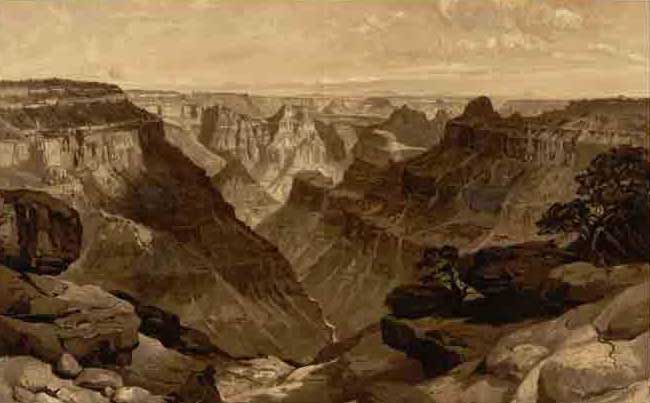

This panorama from Point Sublime is a composite of three sketches produced in 1880 by William Henry Holmes, a geologist and artist who accompanied Clarence Dutton and Jack Hillers to the North Rim that year while Dutton was preparing his Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District. Holmes had also accompanied F.V. Hayden’s survey in 1872. Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

On May 24, 1869, Major John Wesley Powell, his brother Walter, and eight mountain men launched boats into Green River, Wyoming Territory, on a historic quest to travel down the Green and then the Colorado River and through Grand Canyon. Though they were the first Euro-Americans inside the canyon, Powell found ample evidence that humans had lived there for centuries.

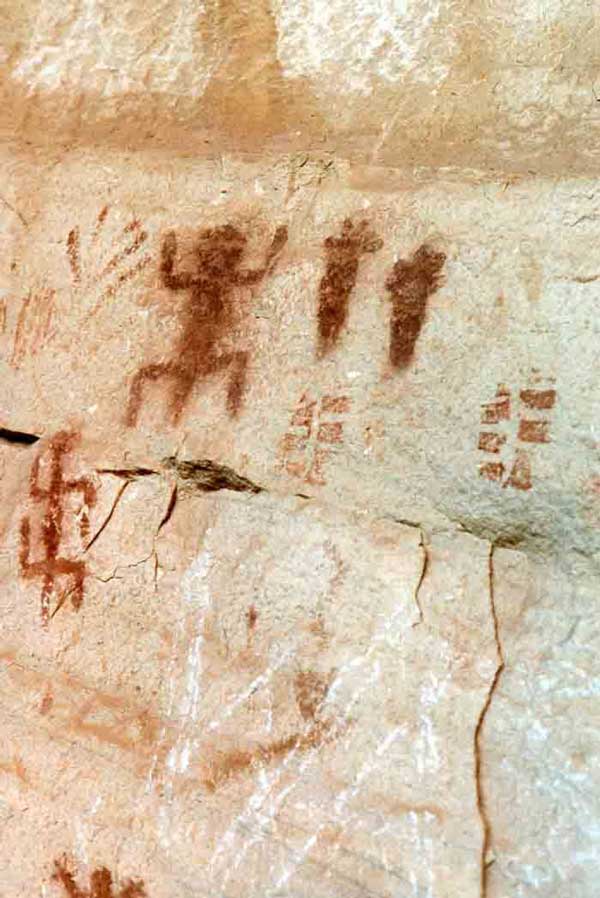

Archaeologists have found evidence of human use of the Grand Canyon dating back at least 13,000 years to the last Ice Age. At least nine contemporary Native American tribes have cultural links to the area, and their oral histories are rich with references to the creation of that great chasm and torrential river. From the sixteenth century on, Native Americans familiar with the region were indispensable guides and informants for Spanish and later Euro-American explorers.

The first Europeans to view the precipice were Spanish explorers under the command of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado. When Coronado’s men led by García López de Cárdenas followed a Native American guide to the South Rim, it was the river below that interested them. They spent three days trying to descend the gorge, only to give up and leave. The vista itself so unimpressed Cárdenas that he made no mention of the trip in his accounts. It would be more than 200 years before any more non-indigenous people traveled to the Grand Canyon.

The Havasupais and Hopis created numerous trails into the inner Canyon, many of which are still used today, but either the routes were too difficult for the armored Spaniards or the Native Americans preferred not to reveal their paths.

Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers led a survey expedition to the greater Grand Canyon area in 1857 and 1858. Ives considered the expedition one of the main events of his life, but his report made him infamous among later Grand Canyon fans. He concluded that the region was valueless, yet even so he wrote about it with a flourish:

“It can be approached only from the south, and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.”

History has proven Ives to be mistaken.

This 1858 hand-colored map, titled “Rio Colorado of the West,” is one of the earliest visual representations of the Grand Canyon area. It was prepared by John Strong Newberry, M.D., a geologist with the expedition led by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives. It was published in 1861 by the U.S. Government Printing Office in the Report Upon the Colorado River of the West, Explored in 1857 and 1858 by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives, Corps of Topographical Engineers, Under the Direction of the Office of Explorations and Surveys, A.A. Humphreys, Captain Topographical Engineers, In Charge.

Photo: Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

The mid-nineteenth century was the age of Romanticism. The American West beckoned those who sought more from life than they could attain in the charted and settled eastern states. It was in this mood that geologists, soldiers, photographers and artists encountered the remote and mysterious Colorado Plateau and Grand Canyon. Many people are familiar with Major John Wesley’ Powell’s role in charting the Colorado River and writing about the greater Grand Canyon area, but there were many others as well.

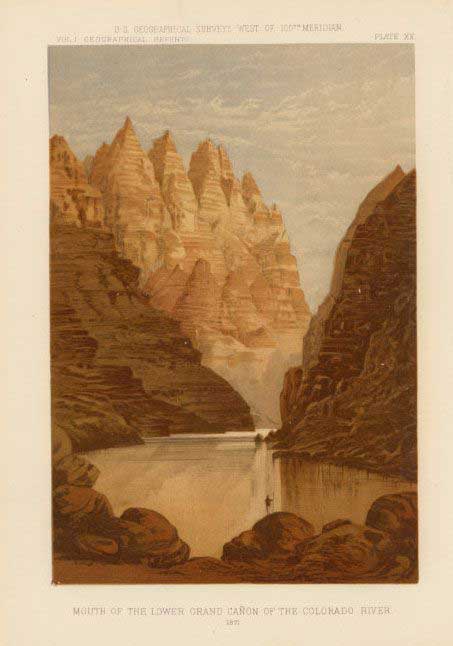

U.S. Army Captain George M. Wheeler led an expedition up the Colorado River in 1871, collecting information and creating the first map that accurately showed the river’s course. Wheeler also took photographs that were published as lithographs in the 1889 Report Upon United States Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian.

The growing knowledge about the Canyon aroused a sense of nationalism. America had this marvelous creation of time and geology – Europe, for all its great achievements and spectacular beauty, had nothing that compared.

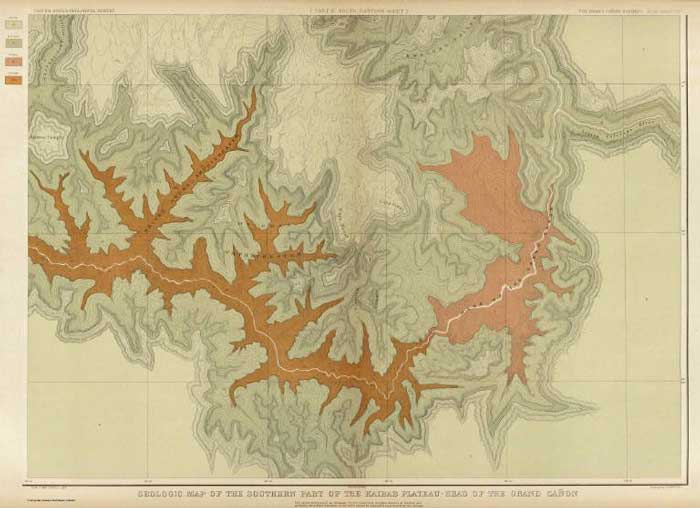

It was not just those in the humanities who waxed poetic about the landscape. The allure drew eloquence from scientists and soldiers as well. Geologist Clarence E. Dutton, who accompanied Powell’s 1875 expedition to the Colorado River, felt compelled to describe the plateaus and chasms of the Grand Canyon area in a literary narrative far beyond the scope of scientific writing. As he acknowledged in his preface to The Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District published in 1882:

“I have in many places departed from the severe ascetic style which has become conventional in scientific monographs. Perhaps no apology is called for… Great as is the fame of the Grand Cañon of the Colorado, the half remains to be told.”

The “Geologic Map of the Southern Part of the Kaibab Plateau” was published in 1882 through the U.S. Government Printing Office in Washington D.C. by Julius Bien & Co. Lithographers in the Atlas to Accompany the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District.

Photo: Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

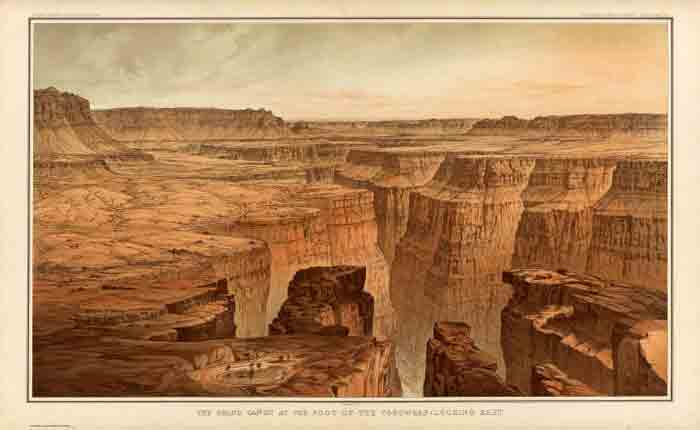

“The Grand Cañon at the Foot of the Toroweap looking East,” sketch by William Henry Holmes, published in 1882 through the U.S. Government Printing Office in Washington D.C. by Julius Bien & Co. Lithographers in the Atlas to Accompany the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District.

Photo: Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Dutton’s Tertiary History described the geology of the plateaus north of the Grand Canyon, but he delivered that information in a narrative that took the reader along for the ride. In his chapter “The Panorama from Point Sublime,” Dutton writes:

“Nothing is seen of the chasm until about a mile from the end we come once more upon the brink. Reaching the extreme verge the packs are cast off, and sitting upon the edge we contemplate the most sublime and awe-inspiring spectacle in the world.

“The Grand Cañon of the Colorado is a great innovation in modern ideas of scenery, and in our conceptions of the grandeur, beauty, and power of nature. As with all great innovations it is not to be comprehended in a day or a week, nor even in a month. It must be dwelt upon and studied, and the study must comprise the slow acquisition of the meaning and spirit of that marvelous scenery which characterizes the Plateau Country, and of which the great chasm is the superlative manifestation.”

Dutton’s Tertiary History remains arguably the most evocative and compelling geological writing ever done on the Grand Canyon region. As Stephen Pyne observes in his foreword to a 2001 reprint of Tertiary History, Dutton “recast a rocky peninsula into geo-poetry, reshaped an amorphous panorama of Time into narrative History, and transformed an American scene into a universal symbol.”

No one who has thrilled to the majesty of the Grand Canyon will fail to be moved by Dutton’s timeless work. There are two reprints of the book, but the original and its accompanying atlas today sell for several thousand dollars on the rare book market. Like the Canyon it describes, the book’s appeal continues.

“Views in the Marble Cañon Platform from the eastern brink of the Kaibab,” sketched by William Henry Holmes. First published in 1882 tin the Atlas to Accompany the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District.

Photo: Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Thomas Moran painted “The Transept, Kaibab Division, Grand Cañon. An amphitheater of the Second Order” based on an 1880 drawing by William Henry Holmes. It was first published in 1882 in the Atlas to Accompany the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District.

Photo: Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

For all the words written about the Grand Canyon, it remains a visual experience. The writers, from geologist Clarence E. Dutton to present-day authors, invariably strive to create mental imagery for the readers. Painters and photographers face a different, yet no less challenging task: How to capture the essence of the canyon’s grandeur.

This painting by Thomas Moran is one of his earliest in a long career of painting the Canyon. Although the details are finely depicted, Moran adapted reality to serve his art. Like Dutton, Moran made no apology for romanticizing the Canyon:

“This Grand Cañon offers a new and comparatively untrodden field for pictorial interpretation, and only awaits the men of original thoughts and ideas to prove to their countrymen that we possess a land of beauty and grandeur with which no other can compare.”

Moran has been followed by countless artists, both professional and simple hobbyists, who have tried to capture the Canyon’s essence.

Explorers and surveyors continued to roam the Grand Canyon area. In 1872, John E. Weyss sketched the Colorado River scene at right, a few miles upriver of today’s Lee’s Ferry and Navajo Bridge. Weyss accompanied a survey expedition led by Capt. George M. Wheeler of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Historically the site was a low-water area used as a travel route by Utes and Navajos. In 1776, Spanish priests with the Dominguez-Escalante expedition crossed the river here, giving it the nickname El Vado de los Padres, or The Crossing of the Fathers. The site was inundated in 1964 when Glen Canyon Dam turned the Colorado River into Lake Powell.

The sketch seems poetic and inspired author Wallace Stegner in 1954 to reprint it in his seminal work, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian. He wrote:

“Weyss reproduced with reasonable fidelity the character of the river, the walls, and the fantastic erosional forms, and managed to put into his picture some of the moonlike loneliness of the spot. The stones marking the ford are like the veritable footprints of the first white men to cross here.”

Since the days of Dutton, Weyss, Holmes and Moran, millions of visitors from around the world have experienced the Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon National Park, which presently protects this stunning landscape, is an artifact of contemporary times and reflects a distinct set of values about the relationship between nature and culture that historians have recognized as an “American” innovation. But those values and the manner in which they have been expressed are not static. The park itself, its boundaries and management policies, its meaning and significance to Americans, its caretakers, residents, and visitors have all evolved in fascinating ways during the past 100 years.

Written By Patricia Biggs

References:

- Dutton, Clarence E. Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District. With an introduction by Wallace Stegner and a new foreword by Stephen J. Pyne. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2001.

- Hughes, J. Donald. In the House of Stone and Light: A Human History of the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1978.

- Morehouse, Barbara J. A Place Called Grand Canyon: Contested Geographies. Tucson: University of Arizona, 1996.

- Pyne, Stephen J. How the Canyon Became Grand. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

- Schwartz, Douglas W. On the Edge of Splendor: Exploring Grand Canyon’s Human Past. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research, 1989.

- Report upon United States Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian, in charge of Capt. Geo. M. Wheeler, Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army. Government Printing Office, 1889.

- Report Upon the Colorado River of the West, Explored in 1857 and 1858 by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives, Corps of Topographical Engineers, Under the Direction of the Office of Explorations and Surveys, A.A. Humphreys, Captain Topographical Engineers, In Charge.