If you’re curious about Grand Canyon geology and looking for a good viewpoint to peer into the inner Grand Canyon, Yavapai Observation Station on the South Rim is made to order.

When the Grand Canyon became a national park in 1919, the Canyon’s importance to the study of geology was already well known. The National Park Service, as well as educational and scientific leaders around the country, soon began looking for a way to convey the wealth of geological information exposed at the Grand Canyon to visitors so that they could more fully understand and appreciate what they were experiencing. The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, Carnegie Institution of Washington (now known as the Carnegie Institution for Science), and the American Association of Museums consulted with each other and decided to design and fund a small trailside geology museum for the park.

The museum planners called upon some of the premier scientific minds in the nation to help design exhibits for this facility, including men from the National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council, and Geological Society of America.1 There were many stories to be told about the Canyon, but these men concluded that the structure should be used to emphasize the geologic story of how the Canyon was created. After a great deal of study, the group determined that Yavapai Point was the best place to locate this structure because all the major features of canyon geology they wanted to interpret could be seen from that rim viewpoint. It thereby became known as “the key to the Grand Canyon.”2

Constructed of native Kaibab limestone and ponderosa pine, this building was the first museum and formal interpretive structure in Grand Canyon National Park. It was also just the third formal interpretive structure built in the national park system, preceded only by two other structures in Yosemite National Park built in the 1920s. The building is an example of park rustic architecture, which incorporates local materials into its design as a way of blending into its environment.

The structure was completed in 1928 using the designs of Herbert Maier. Maier, also known for his structures in Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks, designed the building to “fit into the landscape rather than to dominate it” by mimicking the flat rim surface with a flat roof and molding the station’s terrace to the contours of the canyon rim.

Although it was originally known as the Yavapai Point Trailside Museum, for many years GCNP superintendents and naturalists alike strongly resisted the designation of “museum” for the site and insisted that it be called an “observation station.” Instead of a place with dry exhibits set behind panes of glass, they wanted it to be a place for the dynamic exchange of ideas, where the public could come to see and hear the story of the Canyon and leave with a deeper sense of connection to it. Because of both its architecture and its emphasis on interactive interpretation, Yavapai Observation Station became a model of interpretive facilities for national parks throughout the country.

The early station was originally open to the weather, with one room serving as an observation area and another as an exhibit area. Edwin McKee, a personality who looms large in the history of interpretation at the Grand Canyon as the park’s chief naturalist for most of its first decade, set up the first exhibits at Yavapai Observation Station. He and his assistant Louis Schellbach, who later became chief naturalist himself, left a lasting imprint on canyon interpretation through their dynamic talks and enthusiasm for presenting the geologic history of the canyon. An employee later recalled that crowds loved Louis Schellbach’s lectures because he was a “superb” interpreter whose animated facial expressions and dramatic stories entertained and delighted audiences.3 In the 1950s, Chief Naturalist Paul Schulz identified the daily Yavapai Observation Station lecture as the single most important duty of naturalists at the canyon because “that was the Park story, the whole damn story.”4 When Schulz worked there, the talk lasted from 45 minutes to an hour with no illustrations except the canyon behind him. In this relatively brief period of time, the ranger was supposed to talk about how the canyon was formed, life through the ages, the canyon as a barrier, indigenous ethnology, and more.

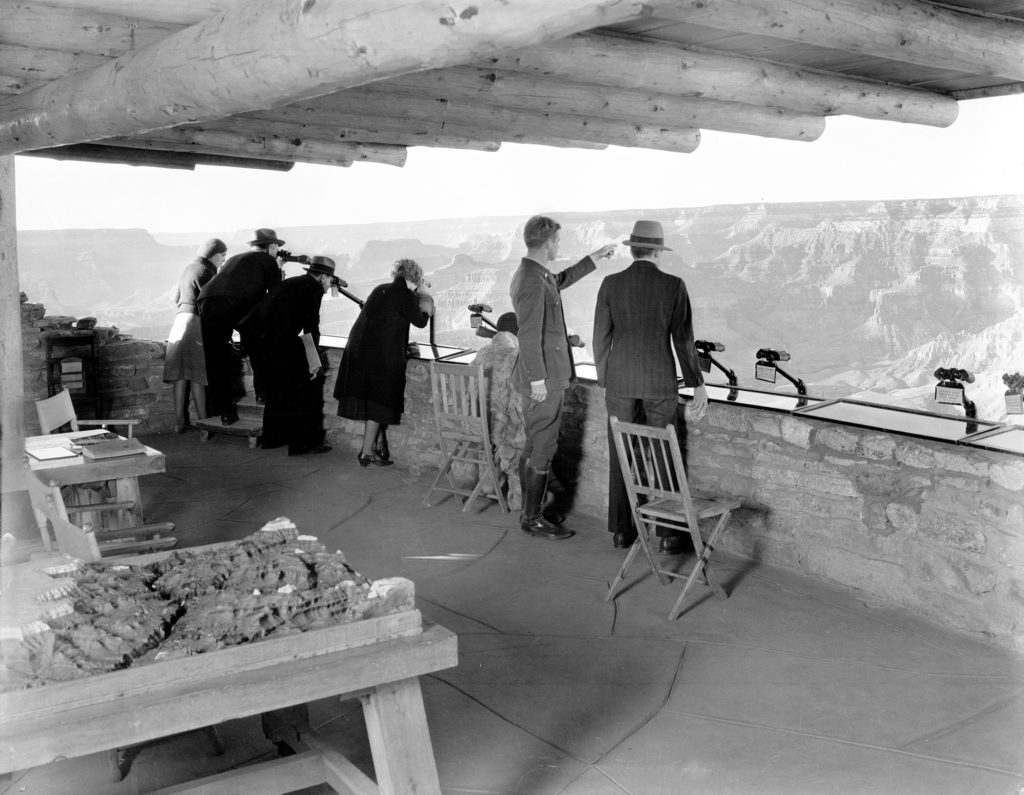

McKee’s and Schellbach’s popular interpretive talks made the canyon’s geologic history more accessible to the public, as did the popular fifteen telescopes and several sets of binoculars mounted in the station for visitor use. When viewed in consecutive order they were meant to show the geological story of the canyon chronologically, as well as provide a closer look at Phantom Ranch, the North Rim, and other sites.5

The interior of the station also showcased the canyon’s history through exhibits including a model of the Grand Canyon, samples of its geological layers, plant and animal fossils, specimens of modern flora and fauna common to the region, and maps and charts for public use. The station had an exterior border of gardens using wild native plants of the canyon to display the diversity of plant life at the park, from the Canadian Zone of the North Rim to the Lower Sonoran Zone of the Inner Canyon.

This building underwent a few alterations to arrive at the layout we see today. To provide a bit more protection from the elements, park architects in the 1950s enclosed the observation deck of the building with glass windows and added more public seating for the popular interpretive lectures given by the NPS staff.

Though much of the rest of the park shut down operations during World War II, Yavapai Observation Station was deemed so important that it remained open for the duration of the war, with interpretive talks still given daily. By 1950, Yavapai Observation Station, “the only one in the park offering Grand Canyon’s ‘full story,’” had become so crowded that motorists parked in the woods along the road a quarter mile away to attend programs.6

Yavapai Observation Station was never large enough to handle the crowds that kept flocking there, and problems such as a lack of funding often left the small interpretive workforce unable to update displays or provide the kinds of programs they dreamed of at this site. Despite these setbacks, the Yavapai Observation Station endured as a popular viewpoint and interpretive facility for visitors to the canyon’s South Rim.

In 1990, the structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places and rededicated as the Yavapai Observation Station with a bookstore inside. More recently, the Yavapai Observation Station underwent renovations starting in 2005, and on May 24, 2007 the building was once again rededicated with new geology interpretive exhibits.

Today, Yavapai Observation Station continues to educate and inform visitors about the Grand Canyon in much the same way that it has for the past 80 years. The station’s large interior windows stretch across the building, affording visitors sweeping views of the north rim and the inner canyon. From here, visitors can see the Colorado River, the Black and Silver Bridges stretching across the river, and deep into the canyon. Inside the center, a variety of interpretive displays explain the deposition of the canyon’s stratigraphy, the uplift of the Colorado Plateau, and the role of the Colorado River in carving the Grand Canyon over time. These exhibits are augmented by daily interpretive talks conducted by National Park Service rangers about the Grand Canyon’s geologic history.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke and Yolonda Youngs

Footnotes:

1NARA Box 89 F D3415 Museum building File 1925-1949 [2/2]. J.R. Eakin to Frank Spencer, Dec 2, 1926; John Merriam to Stephen Mather, May 5, 1927. NAU Cline Library MS280 Fred Harvey Co. McKee to Stitt, 1978. McKee lists out the specialists by their topic, including preeminent figures such as geologist N.H. Darton and F.E. Matthes, paleontologist Charles Gilmore, astronomer Fred E. Wright, and geomorphologists and biologists including Harold Bryant, who would later become superintendent of the park.

2NAU Cline Library MS280 Fred Harvey Co. McKee to Stitt, 1978

3Schulz oral history pg 4.

4Schulz oral history pg 3.

5NARA Box 114 K1815 Naturalist and Educational Activities 1930-1945. Schellbach to John R. Fitzsimmons, Nov 26, 1941

6Michael Anderson, Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park (Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Association, 2000), 51.