Yahoo! This law passed by Congress reads like an invitation to scurry west and stake your claim to freedom, adventure, and prosperity. Many historians agree that this is the very message the federal government intended in order to promote rapid settlement and development of the West. Along with the 1872 Mining Law, Congress gave generous land grants to the transcontinental railroads and free homesteads to farmers. “Go West, young man” was not an idle slogan.

Federal administrators have tweaked the 1872 Mining Law over the years, but its early tenets contributed to western settlement and exploitation as effectively as the Homestead Act of 1862. Essentially, federal law allowed free access to any public land (with minor exceptions) for the purpose of mineral prospecting. If a prospector discovered valuable minerals he could file a claim to them with the General Land Office. To maintain the validity of a mining claim a claimant only had to perform $100 worth of “assessment” work each year. If the mineral deposit proved profitable, the claimant could apply for title (ownership) of the surrounding land for the nominal fee of $2.50 per acre.

Aside from these promotional policies, there was little oversight of mining activity in the 19th century. Arizona mining law was bare bones, requiring little more than that prospectors register claims with their County Recorder. Real organization and specific rules rested with individual mining districts, which the miners themselves formed to fit the particular landscape. Prospectors eventually formed nine or so districts within and near Grand Canyon, setting the maximum claim size at twenty acres, the value of labor at five dollars per day (toward satisfying the annual assessment requirement of one hundred dollars), and no limit to the number of claims one man could hold.

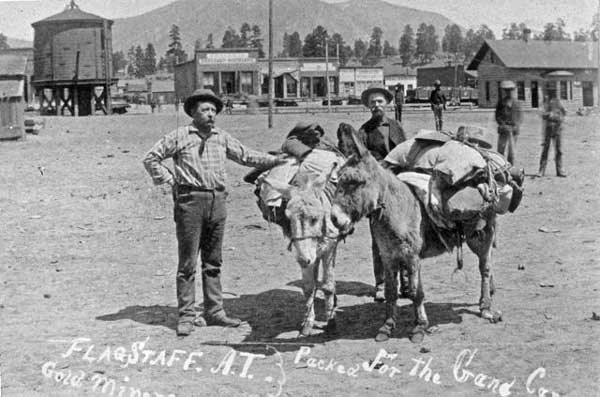

By the early 1870s, many of these men had become skillful, hardened professionals within the gold and silver fields in California, Nevada, Colorado, and Idaho when they reached the canyon’s rims for the first time. Imagine their astonishment as they scanned one of the most awesome geologic landscapes on Earth. They saw the canyon as a pretty place, perhaps even inspiring, but they were realistic men in search of a living so their minds focused primarily on the geologic wonderland, the hundreds of side canyons, creeks, springs, and the Colorado River itself that must, absolutely must, contain mineral wealth. They looked around for animal and Native American paths down into the canyon, and then roughly improved them to facilitate passage of their horses, mules, and burros. The “rush,” so to speak, was on.

The history of western mining is usually told in episodes of gold and silver discoveries leading to “rushes,” booms and busts, like in California’s Sierra Nevadas, the riverbanks and deltas of Alaska’s rivers, or the high mountains of Colorado. It did not happen that way at Grand Canyon.

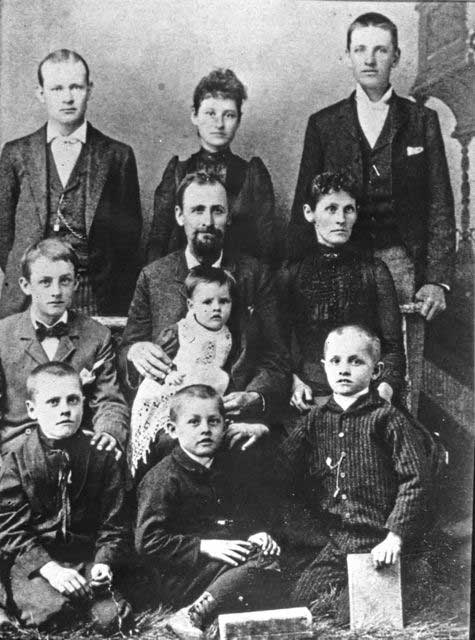

William Henry Ashurst was one of the earliest prospectors within the Grand Canyon Mining District. A resident of Flagstaff, he roamed the canyon’s depths from about 1880 until his death in a rockslide in 1901. His son Henry Fountain Ashurst (upper left) became a senator from the State of Arizona and introduced the legislation creating Grand Canyon National Park.

Photo: Arizona Historical Society-Flagstaff, Edward Ashurst Collection, AHS.335.4

Ralph Cameron’s brother Niles generally managed Ralph’s interests at Grand Canyon and took part in building trails and prospecting. Niles once suggested that he and Ralph file a homestead claim at the canyon in their mother’s name, and was very much a participant in bogus mining claim schemes. He died in the great influenza epidemic of 1918-19.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, Emery Kolb Collection, NAU.568.8282

Only a very few, limited, and not well advertised rushes occurred here, like at the mouth of Kanab Creek in 1872, within the Nankoweap Basin more than a decade later, and at Lees Ferry and upstream into Glen Canyon in the early 1900s. Only precious metals such as gold and silver will spawn a lasting rush, and although placer gold was found at each of these places, its ultra-fine consistency proved impossible to extract at a profit.

Serious prospecting and actual mining operations awaited completion of the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad across northern Arizona in 1882-83, making it much more economical to ship less precious minerals found at Grand Canyon such as copper, asbestos, and lead. Robert Brewster Stanton’s ill-conceived railroad survey through Grand Canyon in 1890, and immediate publication of his mineral finds, accelerated prospecting ventures as well as corporate mining activities along the Colorado River’s banks into the early 1910s, but again the gold proved illusive and the efforts failed.

For a generation, prospectors and miners operated with a no-holds-barred attitude toward mineral development and land use. Progressive ideals for rational land management and conservation did not enter the popular debate and the halls of government until the 1890s. People today may find it difficult to imagine the earlier free-for-all entrepreneurial environment, but recall that the United States had just acquired the American Southwest from Mexico in 1848, and politicians were eager to populate the newly won lands with its citizens.

Conservationists campaigned for more restrictive policies after 1890, but Grand Canyon prospectors and miners operated under lax regulations long enough to stake a large number of claims—many of them merely speculative and some downright bogus—that shaped land ownership and use at the Grand Canyon for generations.

One of Congress’s first efforts to rein in uncoordinated and often destructive development on federally owned lands was the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, which authorized the president to establish forest reservations to protect timber and watersheds of navigable rivers. Using his new authority, President Benjamin Harrison in 1893 declared the most visited, central portion of the canyon a national forest reserve, but the declaration did not preclude prospecting or mining. President Theodore Roosevelt designated much of the same area as a game preserve in 1906, but this proclamation also had no influence on mining. Only in 1908, with Roosevelt’s declaration of Grand Canyon National Monument (created under the authority of the 1906 Antiquities Act), were private land claims no longer permitted within the monument’s boundaries. This ended the opportunity for miners to stake new mining claims in the monument, but it did not affect existing valid claims.

Within the 40-year span of Grand Canyon’s mining history, less than half a dozen copper and asbestos mines and one uranium mine turned a profit. The most valuable of these were located within breccia pipes—fingers of highly mineralized layers concentrated within ancient limestone sinkholes exposed by erosion. In 1947, one of the canyon’s many prospectors, J.A. Pitts, explained why very few efforts paid a living wage when he recounted a trip made with many of the canyon’s noted prospectors in 1891-92. After outfitting in Flagstaff nearly 80 miles from the South Rim, he and the others traveled down what is today called the Old Hance Trail to the Tonto Platform 3,200 vertical feet below, then west to Indian Garden and down another 1,500 vertical feet to the Colorado River. They crossed in a rickety rowboat, walked up a side canyon, most likely Bright Angel Creek, and worked four winter months digging copper ore. After piling up a “nice little bunch of ore,” they had to pack it on burros, move it down to the river, unload the animals and load the ore into canvas rowboats, swim the animals across, reload them on the other side, and climb 4,700 vertical feet up to the rim.

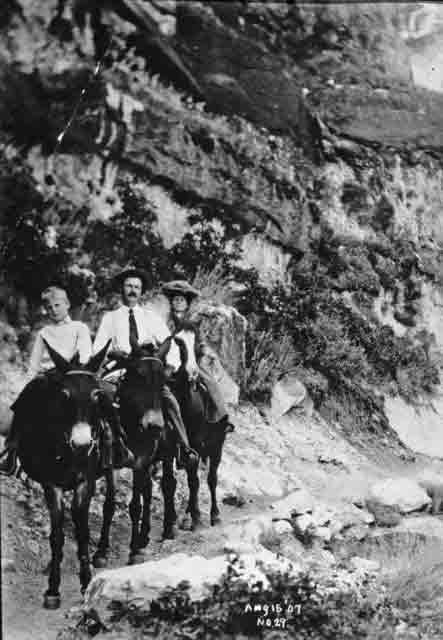

Ralph Cameron was the single most influential private citizen at Grand Canyon from the late 1880s through the early 1920s. He participated in many mining activities at a management level, but was more of a businessman and politician. Pictured here are Ralph Cameron, his wife Ida Spaulding, and their son.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, Emery Kolb Collection, NAU.PH.568.7081

They then loaded the ore in a wagon and hauled it back to Flagstaff, where it was assayed at $20 per ton, less than it would cost to ship by rail to the nearest smelter in El Paso, Texas. They dumped the entire load in disgust and went away shaking their heads. Pitts recalled that since that “mining adventure I haven’t been seized with a desire to travel those trails again.”

Pitts’ experience was typical, but a few lucky men did do somewhat better. To the west of today’s Grand Canyon Village, William Wallace Bass filed on a dozen or more copper and asbestos claims along his trails from rim to rim, and diligently stockpiled ore each winter from the late 1880s through the early 1900s. By his retirement in 1917, he had improved his trails and built a second cable tram across the Colorado River at Hakatai Canyon to facilitate shipping the ore.

He endured all the hardships described by J.A. Pitts and more, but he managed to get all the high-grade ore out and shipped during World War I, when worldwide prices for most minerals were high.

Bass grossed perhaps $10,000 for the copper, and sold six tons of asbestos to buyers from China, France, and the eastern United States for $1,500 per ton, enough to fund his family’s retirement to Wickenburg, Arizona, where he died in 1933. Bass’s nest egg was supplemented by the sale of his valid mining claims to the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company in 1926, for $25,000.

Other successful miners included Pete Berry and Ralph and Niles Cameron, who, with a few other partners, built the Grandview and Bright Angel Trails and filed hundreds of mining claims along the South Rim and down to the Colorado River. All but a few of these claims were bogus—that is, they were filed simply to tie up chunks of canyon real estate that might someday prove valuable—but their Last Chance copper claims atop Horseshoe Mesa turned a profit on their own. The Last Chance eventually comprised seven levels and nearly a mile of horizontal and vertical shafts within the Redwall Limestone. Between 1892 and 1907, it produced 15% to 70% pure mineral, more than enough to ship and smelt at a profit. Like Bass, the partners earned still more money by selling their claims to a larger entity, the Canyon Copper Company, in 1902. This company stepped up production and shipped more than a thousand tons of 30% copper ore at 15 cents per pound and higher before the bottom fell out of copper prices in 1907.

patented into private land. Seven shaft entrances connected by trails still penetrate this breccia pipe in the Redwall Limestone like so much Swiss cheese. The mines consistently turned out the purest copper ore within Grand Canyon in 1891-1907, but did not return to federal ownership until 1939, when the US government employed eminent domain (condemnation) against the last private owner, William Randolph Hearst.

Photo: Seaver Center for Western History Research in Los Angeles

Berry and the Canyon Copper Company then made money by selling their interests to William Randolph Hearst in 1913, Berry netting $42,000 for his homestead and hotel at Grandview and the company earning $25,000 for the Horseshoe Mesa claims and Grandview Trail.

Ralph Cameron shared in the Last Chance sale to the Canyon Copper Company in 1902, but otherwise made nothing from ore extracted from his hundreds of mining claims amassed during the late 1880s through 1908. He very likely never extracted or shipped an ounce of ore because all of his mining claims were barren of valuable minerals, filed solely to tie up strategic parcels of land from which he would benefit in later years, mainly from tourism. Despite the fact that the federal government’s General Land Office declared all of his claims invalid in 1909, Cameron’s political offices and friends as well as lengthy lawsuits allowed him to keep most of them into the 1920s. The Santa Fe Land Improvement Company bought some of his rim side claims along the West Rim in 1912 for $40,000, for no other reason than to obtain a right-of-way to build Hermit Road. The land company bought more of Cameron’s claims along Bright Angel Trail in 1916, just to keep him from developing a dam and hydroelectric project in the Tapeats Narrows below Indian Garden.

Like Cameron, several other early prospectors produced little ore but made money selling their claims to investment companies or the federal government, including John Hance, who sold his asbestos claims along the Colorado River to Massachusetts investors in 1901 for $6,250.

By far the most successful mining venture at Grand Canyon was the Orphan Mine, located a scant two miles west of Grand Canyon Village. The Orphan was first prospected by Daniel Lorain Hogan in 1891. The claim, centered on a breccia pipe at the head of Horn Creek Canyon, measured 20 acres (the maximum allowed by the Grand Canyon Mining District), with a little more than four acres on the rim and the rest stretching down into the Coconino Sandstone. Hogan, who lived to reach 90 years of age, worked the copper claim on and off into the 1940s, but there is no evidence that he shipped any ore.

After Hogan sold his claim to Madeleine Jacobs in 1947, she discovered that the breccia contained some of the richest uranium deposits in the American Southwest. Successive corporate ventures shipped perhaps $40 million in uranium ore between 1953 and 1969, after which government price supports ended and the mine closed down.

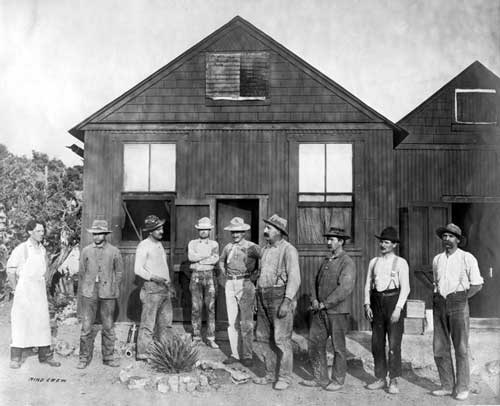

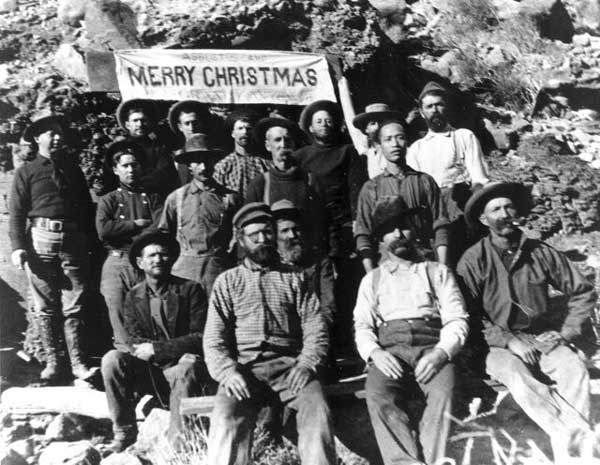

History tends to remember the prospectors who struck minerals and started mining ventures, not the names of the common laborers hired to work the mines. These men line up at the Hance asbestos claims on the north side of the Colorado River at Christmas time, 1902. These claims remain the only private land still within the original park boundaries.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, Emery Kolb Collection, PH.568.3360

Despite these few success stories, Grand Canyon mining produced very little wealth during the pioneer period. Nevertheless, it was the most important human endeavor pursued in these years, shaping the canyon’s developmental history in ways that are still felt in the twenty-first century.

First, these men and their families developed the earliest transportation infrastructure from the railroads and population centers to the rims and throughout the inner canyon. John Hance and partners built the early road to the South Rim from Flagstaff in 1885, which by 1960 was rebuilt and realigned to become AZ 180. Buckey O’Neill promoted the railroad from Williams instead of Flagstaff to today’s Grand Canyon Village in the late 1890s because of copper claims along the route within the Francis Mining District. Bill Bass, David Rust, Ralph and Niles Cameron, Pete Berry, John Hance, Seth Tanner, Franklin French, and other prospectors built the earliest transcanyon corridors that are still used today, and most of today’s popular rim to river trails, in the years 1884-1907. Succeeding tourism and scientific endeavors depended on this infrastructure to get off the ground.

Second, although the miners worked hard to scratch a living at mining and eventually failed, they came to know the inner canyon like their own back yards. They used this knowledge to establish equally meager tourism operations at a time when tourism was not considered an important economic activity. They improved their roads and trails and established crude camps along the rims near the trailheads. They advertised their services far and wide, sometimes traveling as far as the East Coast to show lantern slides of the canyon’s wonders, and promoted construction of railroads to each rim. As visitation increased by the 1900s, larger corporate entities as well as the federal government began to sit up and take notice of this new economy and its popularity. Within twenty years, they had ousted the pioneer miners-entrepreneurs and had begun to invest the real capital needed to grow the tourism businesses to levels seen today.

Equally important, the development of well-capitalized tourism enterprises ignited legal battles with the most obstinate miner of them all, Ralph Cameron. The twenty-year struggle between Cameron (prospector, miner, tourism operator, and politician with powerful friends) against the U.S. Forest Service, later National Park Service, Santa Fe railroad, and Fred Harvey Company might seem mismatched at first glance.

At National Park Service urging, the Santa Fe purchased Bill Bass’s holdings in 1926, for his valid mining claims but also for the roads, trails, and water sources that he developed from 1885 through 1917. This is the ruin of Bass’s large, covered, water cistern designed to collect gully runoff along the road to Bass Camp. Cisterns were important in an area where little surface water existed.

Photo: Michael F. Anderson

However, Cameron used his close ties to state politicians, a loose but nonetheless literal interpretation of federal mining and land laws, and his own political offices as Coconino County Supervisor, Arizona Territorial delegate to Congress, and U.S. Senator to fight vigorously for his land claims.

Cameron enjoyed many victories and some defeats, not to mention a dwindling bank account, during this drawn out war. But his most important contribution to conservation proved to be his lawsuit against the federal government claiming that Theodore Roosevelt’s proclamation of the huge Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908 was an improper use of the 1906 Antiquities Act. The Supreme Court ruled that presidents did indeed have the power to create large national monuments under the act if the size was necessary to protect the cultural or natural resources at stake. Cameron’s machinations also served as a catalyst for developing, refining, and strengthening public-private (federal-corporate) partnerships that still dominate national park management today.

A fourth role that canyon prospectors and miners played in Grand Canyon’s subsequent development and management entails the “worthless lands” requirement for the creation of early national parks. Alfred Runte and other historians have pointed out that the U.S. Congress vigorously debated creation of parks based in large part on the question of whether the lands they would encompass had economic value. Congress usually excluded from park boundaries lands with obvious profit potential.

The chief extractive economies in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century West were logging, farming, ranching, and mining. Although one could easily intuit that the first three endeavors would not prove economical within a mile-deep canyon, mining might in fact prove lucrative in such a geologic landscape. Grand Canyon’s prospectors and miners therefore spent several decades unwittingly proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the canyon was “worthless,” and thereby justifying national park status, bestowed in 1919. Neither Congress nor anyone else at the time foresaw that national park tourism would eventually become one of the West’s most important economies.

Lastly, Grand Canyon mining induced a formidable administrative headache on the National Park Service in the form of private land inholdings within the park. Both the monument proclamation in 1908, and the park’s organic act of 1919, contained clauses protecting the rights of existing land claims—a common practice called “grandfathering” pre-existing property rights. Many of Grand Canyon’s mines had been patented under the 1872 Mining Law into private land. These parcels of private land within the national park allowed owners the same developmental rights as homeowners and commercial enterprises have to develop their properties. By 1919, miners who had turned to tourism had established camps, liveries, hotels, and other facilities within the canyon and along the rims, such as Pete Berry’s hotels at Grandview, Bill Bass’s lodge at Bass Camp, Ralph Cameron’s hotel within Grand Canyon Village and his camp at Indian Garden, and Dan Hogan’s lodge at the Orphan Mine. The National Park Service was unable to control the activities of these facilities because they resided on private lands. The NPS spent considerable time and money over the next fifty years trying to establish control by acquiring these lands through donation, purchase, and in one instance, condemnation.

Sometimes proving the negative is important in the advancement of scientific knowledge and other human endeavors. At Grand Canyon National Park, hundreds of prospectors and dozens of miners worked tirelessly for nearly four decades proving that the canyon would never be a cornucopia of precious and semi-precious metals. Along the way, their desire to make a buck also proved a positive: that tourism at one of the loveliest places on Earth was profitable.

Written By Michael F Anderson

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael F. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.

- Billingsley, George H., Earle E. Spamer, and Dove Menkes. Quest for the Pillar of Gold: The Mines & Miners of the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon Association, 1997.

- Smith, Duane A. Mining America: The Industry and the Environment, 1800-1980. Niwot, CO: University of Colorado Press, 1993.

- Young, Jr., Otis E. Western Mining: An Informal Account of Precious-Metals Prospecting, Placering, Lode Mining, and Milling on the American Frontier from Spanish Times to 1893. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.