William Wallace Bass developed over 50 miles of inner canyon trails as part of his mining and tour guiding enterprises, more than any other Euro-American pioneer at the Grand Canyon. Like most trails that were developed in and around the canyon, these trails began as animal paths and important ancient and modern Native American trails that Bass simply adapted to his purposes. The Havasupai showed him many routes, and important water sources along them. He originally used these trails to haul loads from his mines, but later built camp sites and overnight accommodations along the trails as rest stops for his visitors. Today the North and South Bass Trails still bear his name, though they have been reengineered by the National Park Service since several original portions of the trail were washed out or buried. These trails are considered extremely difficult and should only be undertaken by experienced and well-prepared hikers.

Bass constructed the South Bass Trail, sometimes known as the Mystic Spring Trail, in the mid 1880s. The name “Mystic Spring” refers to the main water source, and the reason Bass could build Bass Camp in this area of the South Rim. Bass had heard rumors of a spring in the area where he wanted to build his camp, but despite many careful searches he could never find it. Finally a Havasupai friend named Thilwisa, known to Euro-Americans as “Captain Burro,” pointed out the exact location, a spot where water seemed to ooze out of solid rock in a way that seemed almost mystical. After an earthquake in 1900, the spring became much drier. In the 1970s, it took legendary Grand Canyon hiker Harvey Butchart five tries to re-locate it.

Since the South Bass trail follows the natural contours of the land, it is likely that it started as an animal trace. Prehistoric and historic Native American structures along the trail show that they likely developed these traces into a trail as they followed and hunted game. Bass further improved the trail in the last part of the 19th Century and built rest stops using hand tools packed in by burros and mules. He sometimes hired Havasupai to help him construct the trail. It is difficult to find the exact path of Bass’s original trails in areas because wild burro paths crisscrossing the area have obscured the historical route.

Bass Camp was at the head of the South Bass Trail. The seven-mile trail descended nearly 4,400 vertical feet down to the Colorado River, with accommodations historically at Rock Camp and River Camp. The trail first passes through the Kaibab, Toroweap, and Coconino formations as it descends 1500 feet to Mystic Spring on the Darwin Plateau. Originally the trail ended here, which is why it was known as the Mystic Spring Trail. Along this first section of trail is a drainage where Bass lined natural indentations in the rock with cement to collect rainwater and snow melt, a necessity in the Canyon’s arid environment. Near the top of the Coconino Sandstone the trail passes near an ancient Native American granary. Here hikers can also clearly see the crossbedding that characterizes the sandstone, which indicates that it began as windblown sand dunes. At Mystic Spring, which is not on the modern trail, Bass constructed a camp from which tourists could take day trips along the many bridle paths Bass developed over the plateau.

In the mid-1890s Bass worked on linking the Mystic Spring Trail to the Colorado River, at which point it became known as the South Bass Trail. Once across the plateau, it drops through a break in the Redwall Sandstone to reach the Bass Canyon creek bed, where it intersects with the Tonto Trail. As with many trails in the Grand Canyon area, the South Bass Trail is able to descend into the canyon here because the Redwall has been broken by the geological process of faulting.

The South Bass Trail follows the creek bed, passing through red and black Hakatai shale. Bass Canyon has some of the best exposures of the Unkar Group, a rock stratum that is mostly absent in the rest of the canyon due to uplift and erosion. Included in the Unkar Group is Bass Limestone, which contains ancient algal remains that are among the oldest fossils in the Grand Canyon region.

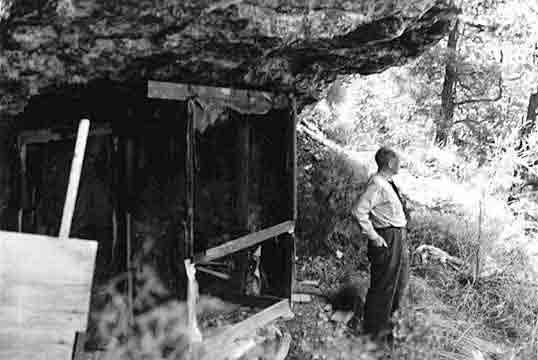

In the bedrock about a mile above the Colorado River are several potholes that form natural water tanks. Near these Bass created Rock Camp, a shelter under an overhanging rock where Bass stored food, a portable forge and anvil, and other equipment to help with his trail building and mining operations. Sometimes the Bass family would spend the winter here to escape the cold weather of the South Rim. The water made the site a good spot for tourists to stop overnight and a place to water livestock.

After leaving Bass Canyon, the South Bass Trail continues over Precambrian Schist until it reaches the Colorado River below Bass Rapid. Here Bass built River Camp, a tent with a stone fireplace where visitors could spend the night before crossing the river or returning back up the trail. Today hikers along the trail will encounter a large cairn that marks a difficult spur down to what is today known as Ross Wheeler Beach, named after a boat abandoned there in 1915. Hikers who continue along Bass’s original trail will pass through River Camp, where they can see the remains of the fire pit he built there. At the beach visitors can enjoy watching dippers, or water ouzels, small gray birds that wade in the water to catch insects.

A few hundred yards away Bass’s trail dropped to the river and a small cove where he built a ferry that he used to convey tourists across the river in a small wooden or canvas boat. It was also an important place in scientific history. In 1902, the United States Geological Survey sent Francois E. Matthes and Richard T. Evans to make the first official governmental map of the western Grand Canyon. They used the South Bass Trail to transport their men and horses across the Colorado River to work on the North Rim in this year, though they used the Bright Angel Trail for the next four years of their work.

In 1906 Bass built a cable tramway in an open spot among the surrounding schist cliffs that made the crossing much more convenient. A cable car could transport several people and equipment, or one pack animal. The river crossing was abandoned in the 1920s, and the National Park Service removed the trans-canyon cables in the 1960s when they became a hazard to rafting parties. Visitors today can still see five cables attached to the schist running down to the river and the ruins of the cable car. The National Park Service rehabilitated the North and South Bass Trails in 2004 to 2005, reinstating more than four miles of original trail. Click here to read about the North Bass Trail.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Babbitt, James, Scott Thybony and George Huey. Grand Canyon Trail Guide: South and North Bass. Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1996.

- Billingsley, George H., Earle E. Spamer, and Dove Menkes. Quest for the Pillar of Gold: The Mines and Miners of the Grand Canyon. GCA, 1997.

- Hirst, Stephen. Havsuw ‘Baaja: People of the Blue Green Water. Supai: Havasupai Tribal Council, 1985.

- James, George Wharton. In and Around the Grand Canyon. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1907.

- “South Bass Trail.” Grand Canyon National Park. Revised 2008.

- Stampoulos, Linda L. Visiting the Grand Canyon: Views of Early Tourism. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.