On the morning of June 30, 1956 two flights waited at the gates of Los Angeles International Airport. Trans World Airlines (TWA) Flight 2 had been delayed a few minutes to complete minor maintenance to the aircraft. Final clearance given, it made its departure at 9:01 a.m. from runway 25 with 70 crew members and passengers on board. Captain Jack S. Gandy was at the controls. He had completed this flight to Kansas City, Missouri over 170 times while with TWA. It was shaping up to be a routine day.

Similarly, United Air Lines Flight 718 had been delayed because of increased holiday traffic, but departed from runway 25L at 9:04 a.m. enroute to Chicago, Illinois. Captain Robert S. Shirley was responsible for the 58 people aboard that day, and like Captain Gandy, he possessed enough experience to make this a routine flight. This morning, however, proved anything but routine for these two captains and their passengers.

Their respective flight plans were completely different. TWA’s flight plan would have taken them north over the San Bernardino Mountains with an airspeed of 270 knots at an altitude of 19,000 feet. United’s flight path would have taken them east over Palm Springs at 288 knots and 21,000 feet.

At 9:21 a.m. TWA Captain Gandy hit some turbulence and requested a change in altitude from 19,000 to 21,000 feet. The air traffic controller, aware that United’s flight plan crossed TWA in the vicinity of northern Arizona, denied this request. As Captain Gandy had likely done many times before, he then asked for a clearance to fly 1,000 feet on top of any weather in his path. Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center approved this standard request, and informed Captain Gandy that United Flight 718 would be trafficking near him.

The last coherent radio communication with the planes occurred at 9:59 a.m. At 10:31 a.m. Aeronautical Radio Communications in Salt Lake City picked up an unidentified radio transmission; it was too noisy to understand, and at 11:51 when contact could not be established with either plane, Air Route Traffic Control Center issued a missing aircraft alert.

The search for the two missing aircraft did not last long. On the day of the crash, a small aircraft pilot operating for a Grand Canyon scenic flights company heard the report of the missing aircraft. He recalled seeing smoke in the canyon earlier in the day. He went out for a second look that evening and confirmed that the wreckage, located in two different areas, was indeed the two missing aircrafts. Search and rescue teams confirmed the find the next morning by helicopter.

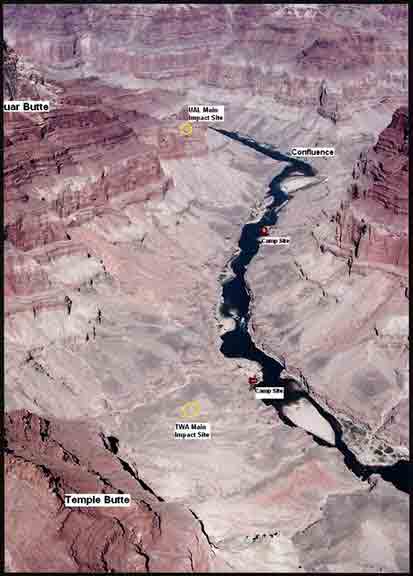

Would-be rescuers faced an overwhelming task. The flight crashed near the confluence of the Colorado River and the Little Colorado River deep inside the Grand Canyon. The TWA flight mainly hit on the northeast terrace of Temple Butte. United’s wreckage was strewn over the southern cliff face of Chuar Butte.

United Airlines brought in a special Swiss mountain rescue team to reach the remains because the wreckage proved too difficult for the conventional search and rescue teams to handle. A paramedic accompanied the first few helicopter rides to the impact site, but it was futile. The searing heat of the crash had melted and fused the aluminum of the airplane bodies to the bedrock, and all 128 people on board the planes perished.

The Civil Aeronautics Board launched an immediate investigation, and concluded that the two airplanes had collided. The rear fuselage and tail section of the TWA Super Constellation were not located near the main TWA wreckage site. It appeared that the left wing of the United DC-7 had separated them from the rest of the aircraft while still in the air. This explained to investigators why the TWA wreckage landed upside down, and why they found no other part of the DC-7 in the Super Constellation wreckage.

The unidentified radio transmission took over two weeks to decipher. It said, “Salt Lake, United 718…ah…we’re going in.” In the background they heard shouts of “pull up!” Both pilots were off their designated routes, and were likely providing a scenic view of the Grand Canyon for their passengers. The investigation concluded that the pilots did not see each other in time to avoid the collision.

The crash was the most deadly civilian plane crash up to that time and remains one of the worst commercial aviation disasters in American history. It demonstrated an outmoded and overtaxed air transportation system. The existing federal Air Traffic Control system could not segregate planes flying by instrument from those flying under visual flight rules, or fast-moving planes from slower ones.

Between 1950 and 1955, air traffic had doubled, and 65 mid-air collisions had occurred. Realizing the critical need for improved air traffic management, President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1955 had appointed Edward P. Curtis as special assistant to develop a comprehensive plan to address the concerns.

The TWA-United airplane crash over Grand Canyon helped spur Congress to act on such concerns. In 1957, Curtis recommended the establishment of an independent Federal Aviation Agency to consolidate oversight of civilian and military flights. In 1958, Congress passed the Federal Aviation Act which created the Federal Aviation Administration as an investigatory and advisory entity. It also modernized air traffic control and implemented stricter flight rules.

Wreckage from the 1956 air disaster is still scattered over the crash sites, and on sunny days people can still catch glares from the gnarled pieces of metal resting on the cliffs of the Grand Canyon near the mouth of the Little Colorado River.

Written By Mark Buchanan and Patricia Biggs

References:

- “Accident Investigation Report,” Civil Aeronautics Board, Department of Commerce, April, 17, 1957.

- Berger, Todd R. It Happened at Grand Canyon. Guilford, CT: TwoDot, 2007.

- “FAA Historical Chronology, 1926-1996,” Federal Aviation Administration web site, online at

http://www.faa.gov/about/history/chronolog_history/ - Ghiglieri, Michael P., Thomas M. Myers. Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon. Flagstaff, Arizona: Puma Press, 2001.

- Historic Disaster led to Air Traffic Control System: 1956, Radarless Airliners Collided above Grand Canyon, Killing 128 Aboard,” The Houston Chronicle, June 4, 2006, 4 star edition.

- Hulse, Jerry. “12 Rescuers Stranded at Scene,” Los Angeles Times, July 3, 1956.

- MacNeil, Neil. “Ike Signs Bill for Highways,” The Washington Post, June 30, 1956.

- Murphy, Shane, Gaylord Staveley. Ammo Can Interp: Talking Points For a Grand Canyon River Trip. Flagstaff, Arizona: Canyoneers, Inc., 2007.