A Visual Experience

Hazy Vision: Historic Views and Air Quality

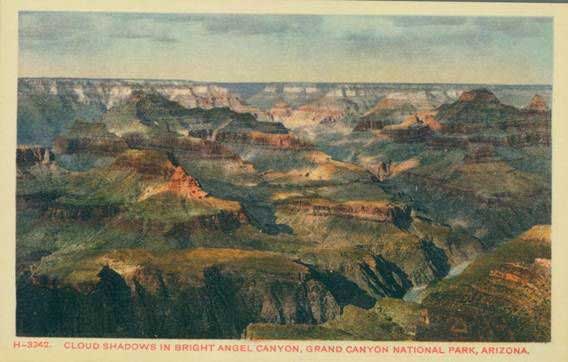

Seeing the Grand Canyon is an experience that draws millions of visitors each year to Arizona. Once at the edge of the canyon, visitors can peer across its vast expanse of color and topography or look down into its deep gorge. Indeed, the act of seeing the Grand Canyon also has a long cultural and visual history. People have been traveling to the Grand Canyon to take in this panoramic view since the late 19th century. They have recorded their views from the rim, river, and along trails in paintings, photographs, postcards, films, and brochures.

Visual Arts Gallery

Celebration of Art

Celebration of Art Book The Grand Canyon Association published this collection of modern paintings from a 2009 exhibition at Kolb Studio on the South Rim of Grand Canyon. The book, Celebration of Art, can...

Landscape Art

Painting across time: Grand Canyon landscapes on canvas During the early 19th century, a young United States compared itself with Europe and, despite impassioned patriotism, often found itself wanting. As environmental historian Alfred...

Photography

References: Braun, Ernest. Grand Canyon of the Living Colorado. San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1970. Evans, Harold. They Made America. New York: Time Warner, 2004. Fitzharris, Tim. The Sierra Club Guide to 35mm...

Re-Photography

Views across time: Selections from the Charting the Canyon project by Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe. The photography professors spent two summers at Grand Canyon, re-imagining points of view of earlier photographers and artists....

Over time, images of the Grand Canyon have been widely circulated and viewed by tens of millions of people. Although this national park now includes over 2.2 million acres and a highly varied geography of side canyons, forests, waterfalls, and streams, it is only a fraction of this total acreage that is recorded in visual representations of this iconic place. A review of the visual record of the canyon in popular media reveals that one of the most common depictions of the canyon is a view taken from the rim looking across the canyon. A panoramic view from the rim is a cultural touchstone; it is the experience most sought by visitors coming to the Grand Canyon.

Exploring the visual history of the canyon reveals something else as well; we like clear views across the canyon. Although photographers, painters, and postcard creators occasionally captured scenes of the canyon partly obscured by clouds and storms, they mostly created images of cloudless days and limitless views across and into the canyon. It is the crystalline air, the deep blue skies, the fiery reds and oranges of the canyon at sunrise and sunset, the shadowed undulations of ridges and draws within this great erosional abyss that we come expecting to see at the Grand Canyon.

This is an important point. Each year, millions of people travel to the Grand Canyon to walk up to that rim, stand there, and gaze into this vast chasm. We want to see the cascading layers of rock falling away precipitously from the canyon rim. We want to see the distant outline of the opposite rim and the vastness of this ancient defile in the same ways that others have seen it as revealed in photography and art. The Grand Canyon is very much a visual landscape, a place that must be seen to be believed, a national park where clarity matters

Not All Views are Created Equal

Over 100 years ago President Teddy Roosevelt urged every American to see the Grand Canyon. Nearly 5 million visitors from around the nation and the world take his advice every year. Indeed, just seeing the Grand Canyon—standing at one of the many fine viewpoints—can garner a breathtaking view whose memories last a lifetime. At some national parks, visitors seek out a variety of activities that all vie for their attention—hiking, camping, biking, and scenic driving to name a few. At Grand Canyon National Park, we come to see.

According to a 2005 Visitor Study of Grand Canyon National Park, visitors who were asked to identify the “highlight of their visit” listed the “canyon itself, spectacular scenic views, and amazing colors.” 1 Research carried out by the Clean Air Taskforce found that visitors to national parks highly prize “beautiful scenery and clean, clear air.” 2 The report also found that other important elements to an enjoyable recreational experience in Grand Canyon National Park included “scenery-related features” such as “colorful rock formations and viewing canyon rims.” 3

Since tourists first started coming to the canyon in the late 1890s, seeing the canyon has been building as a culturally significant rite of passage for Americans. Beginning in the 19th century, photographers, painters, and other illustrators have produced and circulated images of the park. Many of these images were produced for dissemination to a wide audience in the form of postcards, tourist maps, and—more recently—films. Great American artists such as the painter Thomas Moran traveled thousands of miles to explore and paint this grand vista from rim to river and many points in between. The Santa Fe Railroad (a major player in early Grand Canyon politics bringing both money and visitors to the canyon) poured money into bringing painters, sketch artists, and photographers from around the nation to the South Rim. The railroad company provided free room and board right at the edge of the canyon for these creative types. In return, they obliged the railroad company by creating works of art depicting this vast landscape of red stone and cascading light through their gift of vision and artistry, which the Santa Fe Railroad used for publicity.

But not all views are created equal. When we come to see the Grand Canyon, we value a clear view of the canyon. Smog, dust, and smoke are unwelcome.

Although smoke, dust, and humidity are indigenous haze factors in the Grand Canyon, more recent and artificially introduced pollutants also contribute to hazy views of the park. There are increasing threats to the air quality at the Grand Canyon from human-caused and regionally circulated pollutants.

According to a recent report by the Clean Air Taskforce, industrial sources of pollution such as power plants emit pollutants that increase haze and decrease visibility in national parks around the United States. 4 As levels of pollution such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and sulfur dioxide emissions increase these pollutants pose threats not just to human health but to air quality and viewsheds in national parks.5 Air pollution can also discourage tourism and harm historic structures. Human-caused air pollutants have reduced the visibility in many western national parks by 40 to 70 percent. Although recently visibility is improving in many of the national parks, air pollution still limits visibility to some extent in all national parks.6

So, it turns out that there’s more than one way to see the canyon. A recent National Park Service air quality report found that “[a]lthough Grand Canyon National Park is located in a Clean Air Act Class I Area, visibility at scenic vistas is often affected by haze from human sources including metropolitan areas and coal burning power plants.”7

Our understanding of haze is hazy too. Many visitors who travel to the Grand Canyon assume that any haze is bad haze. But there are differences. Our view across the canyon may be obscured by naturally occurring smoke from fires, early morning clouds clinging to the canyon’s walls, dust particles blowing from nearby arid plateaus, or increased humidity.

Visual impediments such as smoke, dust, humidity, inversions, and cloud clusters have been a part of the Canyon’s visual fabric throughout its history. Penny postcards from the early 20th century depict a Grand Canyon filled to the rim with white clouds showing little more of the canyon than the few tops of prominent landmarks such as Isis Temple and Cheops Pyramid emerging through the clouds like islands in a sea of white. Not seeing a clear view across the canyon is also a historic part of the canyon’s visual culture.

But a good view of the Grand Canyon is not hard to find. In fact, thanks to the efforts of interest groups such as the Sierra Club and government agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, a clear view and clean air at the Grand Canyon is protected under the 1990 Amendments to the Clean Air Act.

Congress hereby declares as a national goal the prevention of any future, and the remedying of any existing, impairment of visibility in mandatory class I Federal areas which impairment results from manmade air pollution.8

The Grand Canyon is not alone in this air quality threat. National parks throughout the United States are threatened by human-caused pollution obscuring the scenic views in our national parks.9 In 1982, National Park Service Director William Whalen ranked air pollution and visibility deterioration as the highest threats to national parks (Cahn 1982, 14).10 Indeed, one park commentator portrays U.S. national parks as a canary in a coal mine capable of alerting us to threats that may soon overtake all ecosystems.11 Although protective legislation such as the first Clean Air Act of 1963 and amendments to the act in 1977 and 1990 strengthen measures to reduce air pollution and reduce haze, national park vistas are still in peril from regional haze.

A visual comparison of the best and worst 24-hour average visibility at the Grand Canyon.

The photo and more information can be found at the National Park Service Air Quality Website at http://www.nps.gov/grca/naturescience/airquality_visibility.htm

Photo: National Park Service

Preserving a Good View

Ultimately, we are all responsible for a good view at the Grand Canyon. Through our actions while visiting the Grand Canyon or from afar as Americans interested in preserving our national parks—as cultural and historical landscapes, as symbols of national pride, and as refuges of wilderness—we all can work to strengthen and protect air quality in our national parks.

Novelist, university professor, and eloquent bard of the American West Wallace Stegner once noted just how important a good view of such places as Grand Canyon can be: “We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope.”12

Seeing the Grand Canyon has become an important activity for visitors, an indicator of air quality, and an important visual, historical, and cultural landscape at Grand Canyon. If you’d like to explore this topic in more detail, continue to the gallery section of this website. There you can see historic postcard images, photographs, and paintings of the Grand Canyon and get a glimpse of the canyon past and present.

Written By Yolonda Youngs and Paul Hirt

footnotes

1Arizona Hospitality Research and Resource Center, School of Hotel and Restaurant Management, Northern Arizona University. Grand Canyon National Park Northern Arizona Tourism Study(Executive Summary). April 2005. Available online at http://home.nau.edu/ahrrc/library.asp.

2Clean Air Task Force. 2000. Out of Sight: Haze in our National Parks (PDF). Available online at http://www.net.org/relatives/4213.pdf. Page 8.

3Ibid.

4Clean Air Task Force. 2000. Out of Sight: Haze in our National Parks (PDF). Available online at http://www.catf.us/publications/view/9

5Machlis, G. et al. 2000. A look ahead: Key social and environmental forecasts relevant to the National Park Service. Prepared for Discovery 2000, The National Park Service General Conference, September 11-15, 2000. St. Louis, MO. Available at http://www.nature.nps.gov/socialscience/pdf/A_Look_Ahead.pdf.

6National Park Service. 2002. Air quality in national parks, 2nd ed., National Park Service Air Resources Division, Lakewood, Colorado. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

7Ibid.

8United States Environmental Protection Agency. Clean Air Act 1990 Amendments. Title 1, Part C, Subpart 2, Sec. 169A (a)(1). Available online at http://www.epa.gov/oar/caa/.

9Clean Air Task Force. 2000. Out of Sight: Haze in our National Parks (PDF). Available online at http://www.net.org/relatives/4213.pdf.

10Cahn, R. 1982. The conservation challenge of the 80s. In National parks in crisis. Horstman, E., ed. Washington, D.C.: National Parks and Conservation Association. Page 14.

11Cahn, R. 1982. The conservation challenge of the 80s. In National parks in Crisis. Horstman, E., ed. Washington, D.C.: National Parks and Conservation Association.

12Stegner, W. 1960. The meaning of wilderness in American civilization. In Nash, R. Ed. 1968. The American Environment: Readings in the History of Conservation. Reading: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. Page 197.