When the National Park Service gained control of the Grand Canyon in 1919, one of its first goals was to establish authority and consolidate control over the area, especially at Grand Canyon Village. One aspect of this included gaining quick, easy access to the inner canyon and the Colorado River. For five years, the National Park Service negotiated with Ralph Cameron in an attempt to gain control of the Bright Angel Trail. Cameron operated the trail, the only one in the Grand Canyon Village area that reached the Colorado River, as a toll road and refused to give up his claim.

Frustrated, National Park Service officials decided to build their own trail. They achieved this by constructing the South Kaibab Trail and later the North Kaibab Trail to complete the first trans-canyon trail in the popular Grand Canyon Village area. Experienced engineers and miners perfected techniques for creating inner-canyon trails by their work on the South Kaibab Trail.

The trail was originally called the Yaki or Yaqui Trail because it began at Yaki Point, about 5 miles east of Grand Canyon Village. The trail was later renamed for the nearby Kaibab National Forest. The word “Kaibab” in the Paiute language means “Mountain Lying Down,” their term for the Grand Canyon. The South Kaibab Trail was built from December 1924 to June 1925 under park engineer Miner Tillotson’s supervision. Tillotson later went on to serve as Grand Canyon National Park Superintendent in the 1930s. The trail cuts across the canyon in a northerly direction, dropping through 8 major geologic formations until it ends in the Vishnu schist of the inner gorge of the Grand Canyon. This trail is one of the few in Grand Canyon National Park that follows a ridge line rather than a fault line or side canyons, over terrain otherwise impassible to hikers or livestock. However, it still drops steeply – almost 5,000 vertical feet in about 6.5 miles. The route was chosen because all but a quarter mile of its surface gets year-round sun, minimizing snow accumulation and making it virtually a year-round trail. At the same time, the sun and absence of water along the route makes it a hot and dangerous trail in the summer.

To construct the trail, one work crew started down from the top, while another worked its way up from the bottom. When the Park Service began work the estimated cost of constructing the trail was $40,000, much cheaper than the $150,000 price tag Ralph Cameron demanded for the rights to the Bright Angel Trail. However, problems with weather, financial difficulties, and construction delays resulted in a final price tag of almost $73,000.

The trail provides the shortest access to the Colorado River of any trail on the South Rim, extending only 6.5 miles instead of the 8 miles of the Bright Angel Trail. Because it was meant to be a fast route, it did not follow natural features, but instead was designed to follow the most feasible direct route. Workers blasted much of the trail from Canyon walls with dynamite, compressed air drills, and jackhammers. Still, though its main purpose was utilitarian, the NPS also considered the safety and comfort of future travelers, and today the trail is one of the more popular and extensively used trails in Grand Canyon National Park. It has helped consolidate a great deal of backcountry tourism to one area, helping to preserve more of the Canyon’s fragile ecosystem.

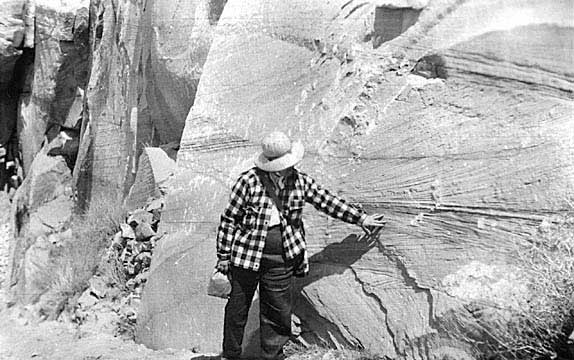

Dr. Agnes Allen points out crossbedding in the Coconino formation along the South Kaibab Trail. Crossbedding occurred when ancient winds blew across sand dunes in changing directions; over millions of years these windswept dunes became preserved as sandstone rock formations.

Photo: NAU.ARC.1947-6-36. NAU Photographic Archives Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

The fact that the South Kaibab Trail was extensively engineered differentiates it from other trails in the canyon. Its steep sections have lower grades than most other trails, averaging 18 percent compared to parts of the Bright Angel Trail that reached nearly 38 percent. The South Kaibab Trail has a uniform 4 foot width and smooth surface with several turnouts and rest areas. Since it was not built by miners, who depended on water for survival and for their mining operations, there is no water available along the trail. It is also open year round, making it possible for mule teams to reach Phantom Ranch at any time so that the site can operate throughout the year. Stone retaining walls help guide the way all along the route.

Interpretive signs along the trail identify major geological periods and rock formations. The upper section begins among the Kaibab Limestone, followed by steep switchbacks that were drilled and blasted from vertical cliffs through the Toroweap Formation, Coconino Sandstone, and Hermit Shale. Hikers can still see the places where the workers who constructed the trail placed dynamite and drilled the rock faces to create the trail. About one mile down the trail from Yaki Point, hikers reach “Ooh Ahh Point,” which provides spectacular views of the canyon.

The trail continues on another half mile to Cedar Ridge, where hikers gain a clear view of O’Neill Butte, named for early explorer and entrepreneur Bucky O’Neill. At this ridge the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s built an exhibit case to display and protect fern fossils uncovered during construction that were left in place to show the evolution of ancient life in the canyon. From Cedar Ridge the trail passes through the Supai Formation and skirts around the east face of O’Neill Butte in a series of switchbacks to the Redwall Formation. Here it drops eastward to the Muav limestone through another series of switchbacks to reach Skeleton Point. From this point, the trail heads through Bright Angel shale of the Tonto Plateau. In the Temple Butte Limestone, the South Kaibab Trail intersects with the Tonto Trail. Taking the Tonto Trail west from this point will lead to Indian Garden.

At a place known as the Tipoff, the South Kaibab Trail descends into the inner gorge of the Grand Canyon. After reaching Panorama Point, where hikers can see and hear the Colorado River 1,200 feet below, the last leg of the trail descends through the Precambrian Supergroup and into black Vishnu schist. Workers building the trail up from the river carved through Vishnu Schist using power tools—likely the first time power tools were used on any Grand Canyon trail. Here a series of short, steep switchbacks plunge to reach the Kaibab Suspension Bridge, also called the Black Bridge, 75 feet above the Colorado River. Hikers can choose to cross the Kaibab Suspension Bridge, or hike a little farther west to cross on the Bright Angel Suspension Bridge, also know as the Silver Bridge, in order to reach Phantom Ranch and Bright Angel Campground on the north side of the river a short way up Bright Angel Canyon. From here, they can continue on to the North Kaibab Trail along the only maintained trans-canyon trail.

The NPS has performed annual maintenance on the trail since 1925 to keep it open year-round. In the 1930s, they used laborers from Civilian Conservation Corps Company 818 to maintain the trail. When citizens of Grand Canyon Village donated a pool table for CCC enrollees to use, a crew of over 100 dismantled it and carried it down the South Kaibab Trail to Phantom Ranch.

Mule trains use the South Kaibab Trail to pack in supplies to Phantom Ranch and NPS facilities in the inner canyon. Yaki Point is used as a staging area, and therefore has several buildings constructed by the Fred Harvey Company and NPS in the late 1920s. The structures include a mule barn, employee residence, hay barn, and several sheds. In 1981 Secretary of the Interior James Watt designated the South Kaibab Trail (along with the North Kaibab, Bright Angel, and Colorado River trails) as part of the National Trails System because of their significant role in transportation and tourism at the Grand Canyon.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Anderson, MichaelF., ed. A Gathering of Grand Canyon Historians. Proceedings of the Inaugural Grand Canyon History Symposium, January 2002. GCA, 2005.

- Shields, Kenneth Jr. The Grand Canyon: Native People and Early Visitors. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

- “South Kaibab Trail.” Grand Canyon National Park. 2008.

- Stampoulos, Linda L. Visiting the Grand Canyon: Views of Early Tourism. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.