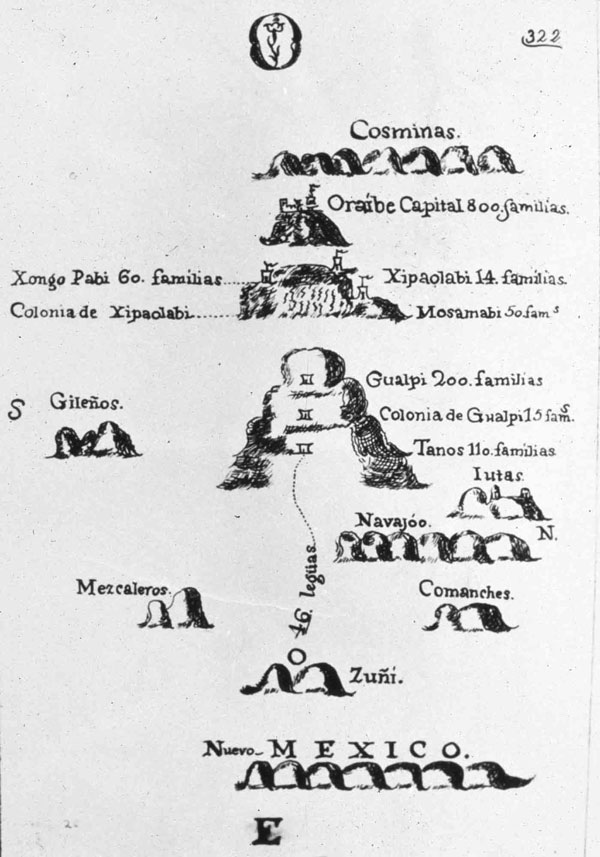

The first Spanish map of the Grand Canyon region was produced by Fray Silvestre Velez de Escalante in 1775. From New Mexico at the bottom (east) he depicts the presence of, distances between, and/or populations of, the Zunis, Mescalero Apaches, Comanches, Navajos, Utes, Hopis, and farthest west, the Cosminas (Havasupais and Hualapais). This map was drawn the year before Fray Tomas Garces traveled from Monterey, California as far east as the Hopi Pueblos, and Escalante and Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez began their exploration eastward from the Rio Grande pueblos toward Monterey.

Photo: Arizona State University, Hayden Library, Arizona Collection.

Harvey Butchart, inveterate canyon hiker of the 1940s to 1980s, personally retraced more than 100 inner-canyon trails, paths, and travel routes within Grand Canyon National Park, yet this number represents far fewer than once existed and far more than are maintained today.

Native Americans have been accessing the inner canyon for food and other resources and for travel between rims since soon after the retreat of the last ice age 13,000 years ago. Spanish priests and explorers lightly touched Grand Canyon’s rims and a few hiked partway down toward the Colorado River, but none left a trace of their passage. Spanish, Mexican, and European-American trappers may also have probed the inner-canyon, but they, too, did not leave physical or paper trails for others to follow.

The first European Americans to leave trails behind consisted of early prospectors and later miners, who needed permanent trails to carry equipment, supplies, food, and ore in and out of the canyon. These men and others slightly improved their prospecting trails to carry the canyon’s first tourists from rim to river. Still later, the Santa Fe Railway, National Park Service, and thousands of backpackers improved and realigned older trails while building a few new ones to facilitate modern tourism. Prehistoric and historic activity created a complex web of inner-canyon trails reflecting their cultural destinations. Most are gone while others fade into oblivion, but several dozen remain vibrant through Park Service maintenance or continuing backpacker use.

Paleolithic, Desert Archaic, and Prehistoric Puebloan hunters, gatherers, and travelers followed animal paths on foot, since they had neither wheeled conveyances nor pack stock to ease their burdens. They were inveterate inner-canyon hikers, pursuing plant and animal foods, springs, mineral deposits, and routes from rim to river and river to rim to visit other indigenous peoples and engage in trade. Through their footsteps, they widened, entrenched, and elongated the tracks they traced.

Later native peoples like the Hualapais, Havasupai, Southern Paiutes, Hopis, and Navajos rediscovered and extended these simple paths for similar purposes during the past millennium. More sedentary native lifestyles of the past century led to diminished use, however, while erosion and other natural factors have obliterated most of these travel ways or returned them to something resembling the animal paths from which they originated.

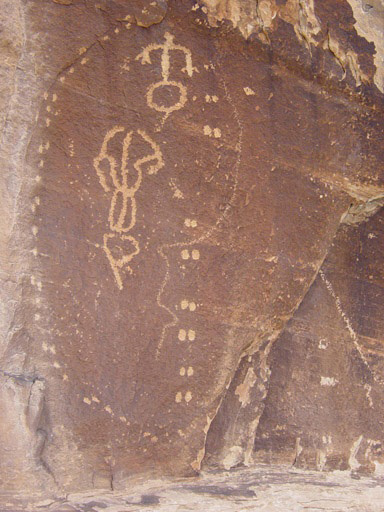

Ancient Native American paths are usually not easy to distinguish from animal paths, or from long-abandoned pioneer European-American trails, for that matter. Still, it is worthwhile to keep them in mind while hiking the canyon’s backcountry. You may stumble upon them while hiking near springs, beside cliff faces, through cracks in the Redwall Limestone and Coconino Sandstone, or in the vicinity of unusual natural features that were (and may still be) considered sacred by native peoples. A smooth line on rough rock, piled stones, or an unusual amount of wood leading up to a cliff ledge, “Moki steps” cut into rock faces, or partially intact ladders connecting or ascending ledges may betray a prehistoric trail. Petroglyphs and pictographs like those found along the Bright Angel Fault may also indicate an ancient travel route or long-lost historic path. If found, they should inspire caution because they may well indicate nearby ruins, lithic scatters, roasting pits, or other archeological sites that must be protected.

Europeans and Euro-Americans began to enter the Grand Canyon region in 1540, when Hopi guides led elements of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s Southwestern entrada to the South Rim near Lipan Point.

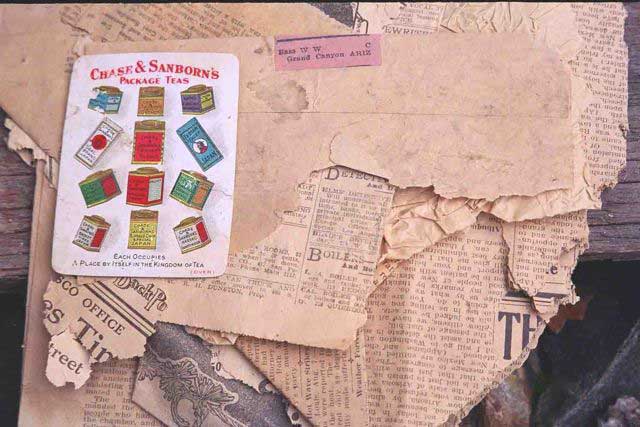

Spanish priests followed in 1776, and Spanish, Mexican, and American traders and trappers thereafter. Few records have yet been unearthed indicating the presence of these men beneath Grand Canyon’s rims, other than a sketchy account of three members of the 1540 expedition who hiked a third of the way down to the river and Tomas Garces’s account of visiting the Havasupai in 1776. A cache of old steel-jaw traps was found in Marble Canyon in the 1990s, however, and at least one historian surmises that Ewing Young’s 1827 trapping party (that included James Ohio Pattie) may have descended in the vicinity of the Tanner Trail and reemerged up the Little Colorado River.

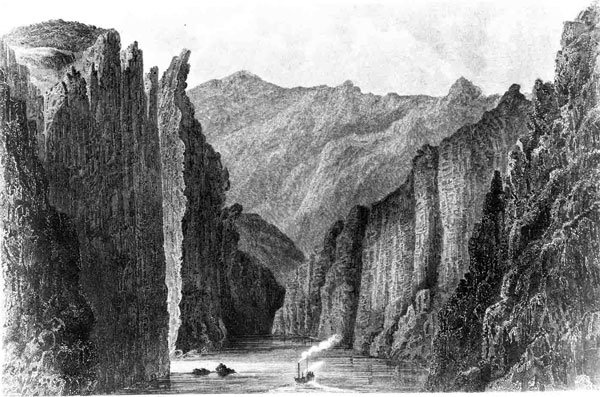

The first recorded visit to the inner canyon by a European American occurred in April 1858, when Lieut. Joseph Christmas Ives’ party of exploration descended to the mouth of Diamond Creek. Their march, which followed a Hualapai route to the river, would lead to a stage road in the 1880s that remains today the only road leading to the Colorado River within Grand Canyon.

You are unlikely to come across paths left by Europeans and Euro-Americans prior to 1870, but there are a host of extant trails that were worn or formally constructed by early prospectors, miners, and tourism operators after that year who improved Native American paths or carved trails out of whole rock. Some are unnamed and their histories obscure. One such is the difficult “Old Miner’s Trail” that leaves the Colorado River Trail west of the silver bridge and ascends the schist to the Tonto Platform. It retains several crude structures and a stacked-stone totem at the top, and was likely built by prospectors before the turn of the twentieth century to reach the river near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek (heavily prospected during 1880-1908). There is a well-built trail from the Tonto Platform to the river west of Cottonwood Creek that may have been the terminal segment of the Grandview Trail. Another leads from the Tonto into lower Hance Creek apparently to reach several century-old mining claims. If you happen upon such a trail, it would help the park’s cultural resources employees if you note what information you can (GPS location, condition, etc.) and report your find for future investigation.

Lithograph of the Explorer in Black Canyon, 1857-58. Lt. Joseph Christmas Ives explored the lower Colorado River as far upstream as today’s Hoover Dam in 1857-58, in the steamboat Explorer. He and his party left the river at that point and explored overland south of Grand Canyon and into New Mexico, declaring that the land was absolutely worthless.

Photo: Grand Canyon Museum Collection.

Early Euro-American trails exhibit certain characteristics that may help reveal their origin. Prospectors, as with other searchers and explorers, seldom wasted time building trails unless there appeared a reason to return. Several routes were used constantly by a series of prospectors making them “arterial paths,” like John Hance’s old trail down upper Hance Creek to the Tonto Platform that was traveled by nearly all south side prospectors until abandoned circa 1894.

Today’s Tonto Trail from the mouth of Red Canyon to Garnet Canyon far to the west proved a virtual prospector’s highway during 1880-1908, the perfect middle avenue to myriad side canyons cascading from rim to river. Both of these trails were later improved for actual mining operations and tourism, but in their earliest form, consisted of well-worn paths, perhaps two feet wide. Examples of the earlier form are found in the Bass Corridor up Shinumo Creek, and between Shinumo Creek and Hakatai Canyon. Generally, they did not include drainage features like steps, checks, and water bars, did not benefit from dirt or crushed-stone fill, and did not include retaining walls except in extreme situations. Prospectors also did not bother with outside walls (“curbs” or “parapets”) above trail tread height. Think in terms of the least amount of effort to allow passage of saddle and pack animals and you may envision Grand Canyon’s early prospecting paths. They are hard to differentiate today from game or earlier Native American paths, so their identification often relies on archival research.

Canyon pioneers were willing to expend more time and effort on trails if prospecting led to mineral discoveries, working mines, or tourism. The Grandview Trail from Grandview Point to Horseshoe Mesa is perhaps the best extant example of a trail built primarily to move supplies into and ore out of the inner canyon via pack animals. Although the trail has received modern maintenance, note the appearance of historic steps, checks, and water bars; retaining walls of dry rubble (wet or mortared, but cut-stone masonry was almost never used); cobblestone rip-rap tread in very steep sections; and cribbing to create trail where a natural path did not exist.

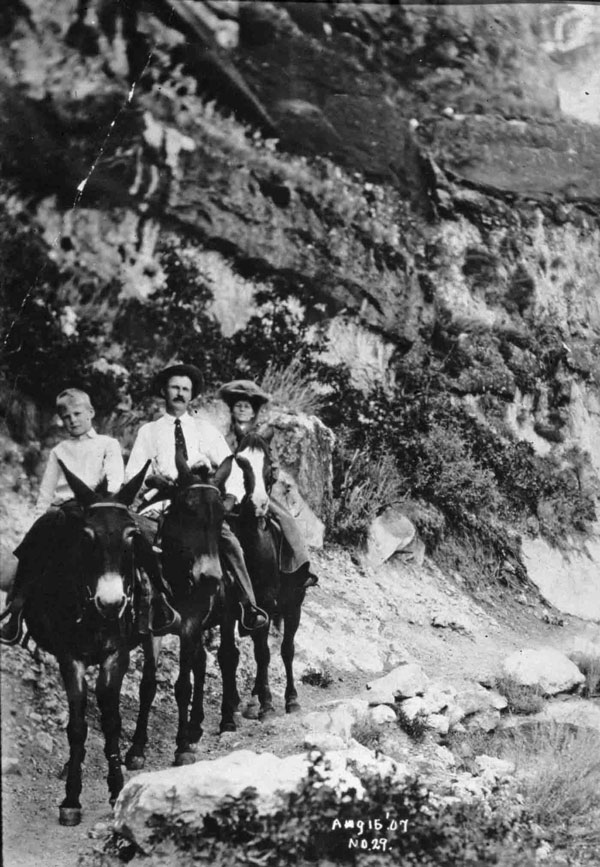

Ralph Cameron, son, and wife Ida Spaulding on the Bright Angel Trail in 1907. Cameron first arrived at Grand Canyon in 1889, and continued to influence its development through 1926. In that time he was a prospector, miner, land speculator (claiming nearly 1,000 mining claims), Coconino County sheriff and supervisor, territorial delegate to Congress, and U.S. Senator from the State of Arizona.

Photo: Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, NAU.PH.568.708.

builders, and we have hardly improved on their methods and materials in the past century. Still, their trails rarely exceeded two feet in width, often were bereft of tread fill, and nearly always descended from the rim in tight switchbacks, or “zig zags” as they were called in older literature, in grades approaching 40 percent (park-era-constructed trails rarely exceed 20 percent). They also used fewer checks and water bars, and may not have entirely understood today’s method of spacing checks to retain the greatest amount of dirt tread. These trails were improved very little to accommodate pioneer tourism. Instead, tourists in the pre-park era led their saddle animals as often as they rode them and commented on “hair-raising” descents in their journals and published materials. Examples besides the Grandview include the oldest alignments of the Bright Angel Trail, today’s South Bass Trail, and remnants of the Old Hance Trail.

Old alignments of modern trails are common throughout the canyon and are sometimes discovered by hikers beside today’s alignments. Their use is discouraged because they are often hazardous and may lead to sensitive cultural and natural resources, but in combination with inscriptions, pictographs, and artifacts they tell us something of early trail building techniques as well as tourists’ predilections for viewing Native American art, littering and writing graffiti.

Pete Berry’s original Grandview trailhead and first half-mile of trail, abandoned circa 1907, and Bill Bass’s original alignment of the North Bass (“Shinumo”) Trail, abandoned circa 1926, are examples of extant though deteriorating older alignments of modern trails.

A route down through the Palisades of the Desert from Cedar Mountain to the top of the Redwall near Desert View hides an early Native American alignment of today’s Tanner Trail. Many of the modern alignments of remote historic trails have been forged since the 1960s by backpackers, who do not need to follow historic switchbacks built by pioneers to accommodate saddle stock.

Major inner-canyon trails built or rehabilitated by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway and National Park Service are all considered historic, since they were completed more than fifty years ago. The Santa Fe funded the construction of Hermit Rim Road and Trail in 1911-12 to state-of-the-art standards, as well as many of the village roads (such as they were) during 1901-19, and the Navahopi Road (precursor of Desert View Road) from the village west to Tuba City in 1924. The park service funded construction of the South Kaibab Trail in 1924-25, the Thunder River Trail from Surprise Valley to Upper Tapeats Campground in 1939, and through the labor of the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Colorado River Trail in 1933-36, Clear Creek Trail in 1933-35, and Upper Ribbon Falls Trail in 1935. Park laborers themselves built the North Kaibab Trail from Manzanita Creek up to Bright Angel Point in 1926-28.

The National Park Service built the South Kaibab Trail in 1924-25 using modern road building tools like the portable compressor shown here. The CCC extended those efforts, building inner-canyon trails for the National Park Service in 1933-37.

Click photo to see two CCC two recruits drilling a hole by hand, a method called “double jacking.”

Hikers and a trail maintenance crew working on the South Kaibab Trail in 2006. Note the switchbacks stabilized by rock retaining walls and metal pipes, and the juniper logs and rock filled tread stabilizing this trail. The South Kaibab Trail is heavily used by hikers and mule pack trains and is one of the most well-maintained trails in the Grand Canyon. Many primitive backcountry trails in the Canyon receive little or no trail maintenance allowing for a broad range of hiking experiences and levels of difficulty.

Photo: Paul Hirt.

With the Hermit Trail, the Santa Fe introduced the modern tourism trail—minimum four-feet wide, stable tread including lots of cobblestone rip-rap, walls or curbs lining the outside of the trail for tourists’ peace of mind (called “parapet” walls in the 1920s), reasonable grades, and rest stops.

With the South Kaibab Trail, built to Hermit standards, the park service introduced modern construction equipment being used on automotive roads at the time, like portable compressors and jackhammers. Along any of these trails you may find dozens of old drill bits (thousands were expended) often used to shore up retaining walls, traces of drill holes in the rock and cliff faces, and “blast fractures” in surface tread or near cliffs caused by the use of high explosives. Although historic construction materials were similar to those used today (basically stone and juniper logs), you may also notice older, usually thicker, foot-polished juniper logs, steel rails, and rebar that is somewhat thicker than most modern rebar.

Enjoy your day hikes and backpacking trips into Grand Canyon’s depths, but please remember that essentially all inner-canyon trails are historic artifacts in and of themselves. Their features, alignments, and the thousands of cultural sites and artifacts beside their footprints are irreplaceable indicators of humanity’s 13,000 years spent below canyon rims. By all means study and photograph any ancient trails and related artifacts you may find, but leave them in place for future hikers to rediscover.

Written By Micheal F. Anderson

(Grand Canyon Association, 1998) and Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park ( Grand Canyon Association, 2000).

Rim to River and Inner Canyon Trails