Hermit Trail, like most other Grand Canyon trails, began as a Native American route. Ancestral Puebloans used paths in the area to hunt and gather plants, as did more modern peoples such as the Havasupais.

After the turn of the century, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway took over the tourist activities in the area. They desired a trail to bring tourists down into the canyon, since at the time Ralph Cameron controlled the Bright Angel Trail, the only route into the canyon in the Village area, and charged a toll to use it. The only other nearby place where a trail down into the canyon could be relatively easily constructed was along the route of the future Hermit Trail. The railroad wanted to compete with local landowners for the profits that came from providing tourists with an inner canyon experience.

The Santa Fe Land Improvement Company, a subsidiary of the railroad, surveyed the route for the Hermit Trail in 1909 and hired the L.J. Smith Construction Company to build it in 1911-12. The railway named it the Hermit Trail after a French-Canadian prospector named Louis Boucher, who lived alone and operated several mines in the area. An eccentric recluse, he earned the nickname “the hermit,” although Boucher was known for always being gracious to any tourists who stopped by his home. Many sites in the Grand Canyon are named after him.

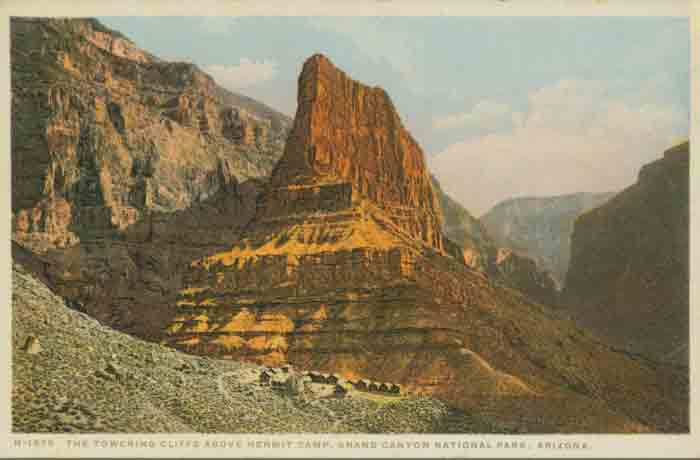

This trail was unique at the Grand Canyon as the only one up to that time designed exclusively for tourist use. At the same time, the railroad constructed Hermit Camp near Hermit Creek on the Tonto Platform—one of the rare areas in the canyon where water was available for tourist facilities. This camp allowed visitors to stay overnight in the canyon before heading either to the Colorado River or back to the rim. The camp area included rest areas, horse stables, and cottages.

The railroad’s partner, the Fred Harvey Company, operated Hermit Camp. Like most Fred Harvey ventures, the company spent a great deal of time and money making sure the Hermit complex provided first-class service and accommodations. Guests could stay in well-appointed tent cabins, which featured stoves, Native American rugs, and windows. Visitors even had electricity, showers, and telephone service. The main building housed a central dining room stocked with fresh fruit, meat, vegetables, and ice. Altogether, the trail and camp cost about $100,000 to construct, an enormously costly project for the time.

In 1914, architect Mary Colter designed Hermits Rest at the head of the Hermit Trail for the railroad as a spot where tourists could relax and enjoy refreshments, and perhaps purchase some curios to remind them of their trip, before starting down to the camp or returning to the Grand Canyon Village. Although it no longer exists, the railroad built an aerial tramway that led from Pima Point to Hermit Camp in 1925-26.

Upon completion, the Hermit Trail became a model for trail construction throughout the National Park Service. The company built the trail to be as comfortable and safe as possible, with plenty of rest stops, a wide tread, and reduced grades, to help make an inhospitable landscape more welcoming and pleasant. At the same time, the trail also had to be durable to withstand the high volume of foot and hoof traffic. Portions of the trail are stabilized with riprap to prevent erosion and feature retaining walls built of stone from each of the major formations it passes through, helping it blend into the natural landscape.

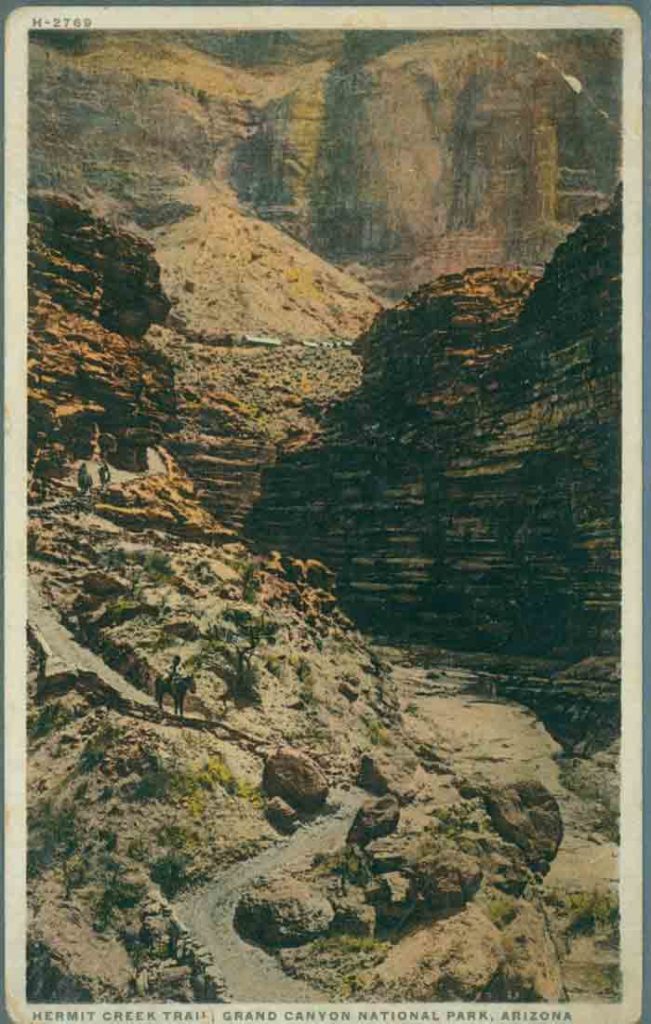

The first section of the 7.5-mile trail drops quickly in a series of switchbacks through Kaibab Limestone and the Toroweap Formation and on to the Coconino Sandstone. In the Coconino are about 1,000 feet of switchbacks known as “the white zig-zags.” A retaining wall built primarily from slabs of native stone borders much of the upper mile and a half of the trail, and there are several continuous sections of well-crafted, hand-laid sandstone creating a smoothly paved walking surface. Imprinted on the rocks here are several fossilized reptile tracks. Blocks of sandstone have been placed to form steps leading to different fossil sites to allow visitors a closer look.

From here the trail descends into Hermit Shale until it meets up with the Waldron Trail to the rim, then the Dripping Springs Trail. After the latter junction it drops into Hermit Gorge, consisting of rocks from the Supai Formation. Because the trail cuts across a slope that crosses high gradient drainages, the Supai section of the trail has been badly damaged by the same erosional forces that helped form the Grand Canyon.

Here, about two miles down the trail from the rim, is Santa Maria Spring and Rest House. The spring provides a reliable source of water year round, though hikers should know it is infected with Guardia and should be treated before drinking. The rest house, built of stone walls with a gabled wooden roof, was built in 1913 at the same time as the trail and Hermit Camp. The roof was renovated sometime before 1922, and again in 1989. There is also a metal water trough on a stone base and a hitching rail nearby, reminders of the days when mules carried tourists and their goods down the trail.

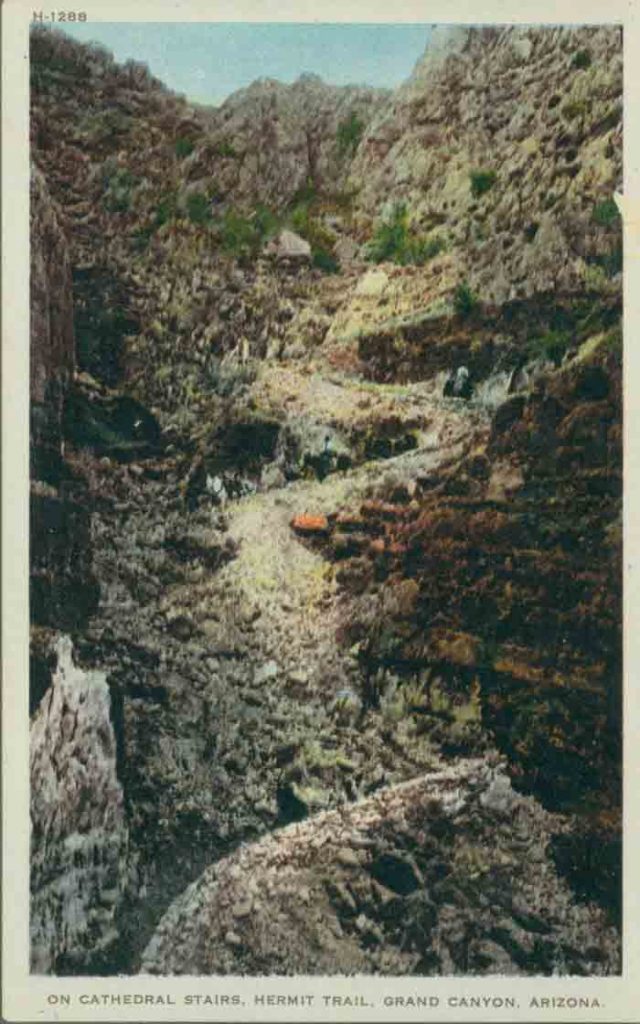

From Santa Maria Rest House the trail heads north along the eastern side of Hermit Creek Canyon then levels off atop the Redwall Limestone, taking hikers to Lookout Point, which offers great views of the inner gorge. Beyond this point the trail drops almost 500 feet through a break in the Redwall along switchbacks known as the Cathedral Stairs. Along this section there is little vegetation, and the trail is mostly made of just earth and rocks. Some blasting was needed to construct these tight switchbacks, which descend the entire limestone layer. Rock retaining walls and stone riprap help protect this section of trail from erosion.

At the Tonto Platform, the Hermit Trail intersects with the Tonto Trail, and the two trails overlap for about a mile until Hermit Trail ends beneath Pima Point alongside Hermit Creek, where Hermit Camp once stood. Here there are several campsites today, and the cool water of the creek is a welcome relief to hot, weary travelers. A bit downstream from the campsites is a gorge and small waterfall. Hikers can continue along the creek another 1.5 miles to the Colorado River and Hermit Rapids, though a major trail was never developed this far and the path is not nearly as well maintained as the rest of the trail.

In its 18 years of private commercial operation, Hermit Camp provided rest and lodging for thousands of tourists at the Grand Canyon. With urging from the National Park Service (NPS), the railroad abandoned Hermit Trail and Hermit Camp in the early 1930s during the Great Depression in order to concentrate its efforts at its newer inner canyon facilities at Phantom Ranch. Several factors made Phantom Ranch a more attractive site. It was accessible from the bustling Grand Canyon Village at the rail head and situated along Bright Angel Creek a short stroll from the Colorado River. The Park Service had recently acquired the Bright Angel Trail from Ralph Cameron and completed the South Kaibab Trail and North Kaibab Trail creating a rim to rim trail linkage that passed through Phantom Ranch. These new constructions were part of a NPS effort to centralize commercial use of the Grand Canyon in a smaller, more centralized corridor to better protect the environment for future generations.

Hermit Camp was left to deteriorate until the NPS ordered the company to dismantle what was left and clean up the area in 1936. Buildings were razed and the tramway was dismantled. On a cold winter night in November, people gathered at Grand Canyon Village to watch the huge blaze as the railroad torched whatever was left. Today the only remnants of the camp include concrete building foundations and sidewalks; an underground cold cellar; a corral; and the tramway’s concrete foundations, steel wheels and cables. These ruins can be seen from many points along the trail.

The National Park Service did very little to maintain the trail from the 1930s to the 1960s. By the 1940s, feral burros and erosion had badly damaged the trail, and it was closed 1.5 miles from the rim. Finally, in the 1970s and 1980s, with the nationwide boom in backpacking and hiking, the NPS launched efforts to stabilize and repair the trail and erect new interpretive signs. Work crews paid careful attention to the historic features of the trails by restoring original cobblestones wherever possible, and by repairing walls by replacing dislodged materials with original material. Today the NPS keeps the trail moderately maintained, making sure the historic qualities of the retaining walls, sandstone riprap, and drainage structures remain in good condition.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Grattan, Virginia L. Mary Colter: Builder Upon the Red Earth. Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1992.

- “Hermit Trail.” Grand Canyon National Park. Revised 2008.

- Stampoulos, Linda L. Visiting the Grand Canyon: Views of Early Tourism. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.