The National Park Service organic act of 1916 called on park administrators to “conserve the scenery…and provide for the enjoyment of same in such manner…as will leave them unimpaired.” The act, nearly a century old, was written during America’s Progressive Era, when professional land managers believed they could harmonize competing interests and when a park’s “scenery” was thought to approximate its ecological health. As knowledge about the environment and its ecology deepened in the past century, and as human pressures on the parks increased, park administrators have faced an increasingly difficult mission to satisfy tourist demands while simultaneously protecting nature.

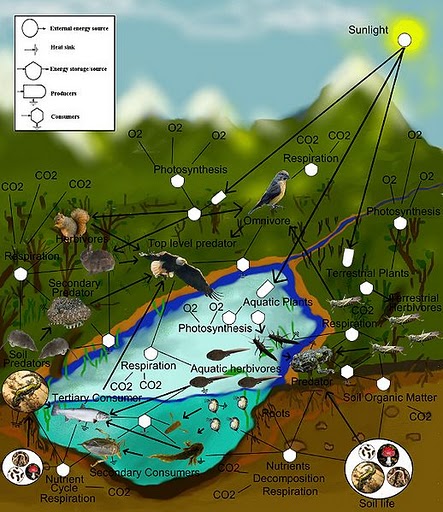

Ecology is a branch of science that studies the patterns of interrelationships between organisms and their environment. Ecosystems refer to the web of plants and animals across a wide scale of size and area. Ecologists might study how organisms adapt to their environment, the distribution and abundance of species within an ecosystem, the movement of materials and energy through living communities, or the patterns of evolution over time.

Healthy ecological communities are those in which all parts contribute to the health and function of the whole. When one element is removed, or another added, the community will be altered. Preserving nature in the national parks thus involves complex considerations of how to manage human use of ecosystems and how or whether to intervene in natural processes like fire, flood, insect infestations, wildlife migrations, and climate change.

Grand Canyon National Park contains several major ecosystems. It also contains five of the seven life zones and three of the four desert types in North America. In fact, if one visited all of the life zones within the park it would be the equivalent of traveling from Mexico to Canada. Though the majority of the park is considered to be semi-arid desert, the 8,000 foot elevation differences within the park allow a variety of different habitats for the hundreds of plant and animal species that make the Canyon area home. Some of the more unique ecosystems that the park protects include boreal forest and desert riparian communities under threat elsewhere. The walls of the Canyon hold many caves which contain distinctive biological systems. The park has three different forest communities: pinyon and juniper woodlands, ponderosa pine forest, and spruce-fir forest. The park also contains grassland communities such as montane meadows, upland subalpine mountain meadows, and semi-desert shrub-grasslands. Soils in the Grand Canyon are fairly poor, eroding easily and regenerating slowly. Most are sandy, allowing them to absorb rain almost immediately, but since they are so fragile they are prone to erosion problems, especially where cattle have grazed and humans have made trails or engaged in mining activities.

The environment and ecology of the Grand Canyon today is very different from that of a century ago. Humans introduced non-native plant and animal species, air pollution obscures the visibility of scenic areas, dams have greatly altered the flow and composition of the canyon’s rivers, construction of roads has led to heavier and more concentrated use of the area, and logging and fire suppression has changed the structure of forests. Though many laws and programs are now in place that attempt to protect and restore the natural landscape, restoring the landscape to its natural state is a difficult, if not impossible, task. Scientists try to eradicate pests and relocate non-native species, fences have been constructed to keep out grazing cattle, dams have considered modifications to their operations, special no flight zones help preserve the solitude of certain areas of the park, and prescribed burning helps restore forest landscapes altered by fire suppression. But with millions of visitors coming to the park every year, the Grand Canyon is unavoidably a cultural landscape with a significant human presence. Still, it is a presence that we now choose consciously to restrain in order to reduce the human alteration of the parks natural ecosystems. The park is for human enjoyment, but in ways that do not impair the park’s natural resources.

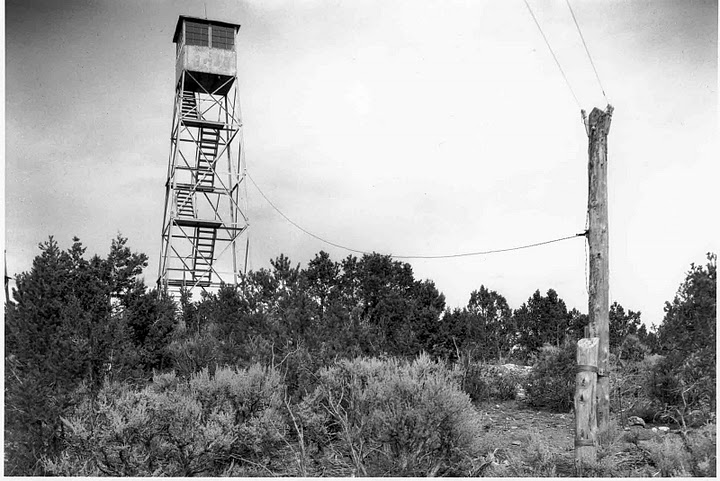

Grand Canyon National Park directed much of the Civilian Conservation Corps’ labor toward preservation & wildlife tasks, like fire prevention (shown here), erosion control along roads and trails, and the construction of earthen water tanks throughout the park.

Photo: Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection.

Early, well-intentioned attempts to manage wildlife at Grand Canyon proved very complicated and illustrated a great deal of ignorance about wildlife ecology as well as anthropocentric goals for managing the parks. In the early years, NPS rangers tended to manage the environment for tourists; in other words, they willingly favored the introduction of exotic species when they enhanced visitor experience, and removed animals they believed tourists would not favor. Park rangers at first continued the Forest Service policy of protecting animals pleasing to both tourists and hunters, such as deer, bighorn sheep, and elk, by exterminating four-legged predators such as mountain lions, bobcats, wolves, and coyotes.

In the 1920s, ecologists began revising their opinions about predators, recognizing that they played an important role in ecosystem health. This change came largely because of the disastrous events surrounding mule deer on the Kaibab plateau. With nothing to restrain their numbers, the native Rocky Mountain mule deer population exploded, consumed all the available browse, and then crashed from starvation in the 1920s. In 1931, Grand Canyon Superintendent Miner Tillotson entirely ended the practice of killing predators in the park.

However, rangers still experimented with introducing pronghorn antelope to the park, propagating wild turkeys, trapping and releasing beaver to control where they established dams, removing feral burros, and otherwise manipulating nature at the Canyon. Many of these early programs to “assist” nature did more harm than good. Still, NPS rangers also did beneficial work such as soil erosion control and revegetation projects they initiated with the help of Civilian Conservation Corps crews and outside agencies.

The introduction of exotic species is one of the most disruptive ecological activities in which humans engage, yet it happens across the globe and even in protected areas like national parks. Today Grand Canyon National Park contains about 155 non-native plant species, or about 10% of the total plant species in the park, and a number of non-native animals such as trout, burros, and mudsnails. These introductions of non-native species were sometimes purposeful and sometimes accidental. Seeds, insects, and even animals can be transported on cars, trucks, and tires. Sometimes these non-native plants and animals thrive and quickly spread because there are no natural predators or biological controls to keep their population in check. They can commandeer the habitat of native plants and animals and squeeze the natives out. The NPS in the 1960s finally adopted a policy of exclusion of all non-native species, but efforts to undo the damage done by prior generations will continue long into the future.

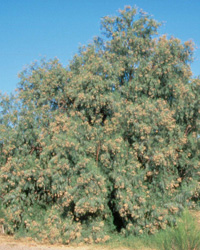

Tamarisk, also known as salt cedar, is a non-native tree that was introduced in the West in the 19th Century for erosion control. Today it has spread rapidly throughout the region, causing major changes to natural environments, especially as the riparian zone along the Colorado River. Tamarisk displaces native vegetation and animals, changes soil salinity, and increases fire frequency.

Photo: NPS Photo

One of the most significant and enduring manipulations of the Canyon ecosystem by the NPS came from efforts to introduce non-native fish to the Colorado River and its tributaries solely to promote sport fishing. From 1919-1964, rangers obtained more than a million eggs and fry of Loch Leven, Rainbow, Black Spotted, and Eastern Brook Trout from nearby hatcheries, laboriously packing them in aerated cans on mules to get them to the bottom of the Canyon. On at least one occasion rangers planted freshwater shrimp to feed the trout, and the NPS even established their own field hatchery to keep the rivers stocked. Fish stocking ended in 1964 after the completion of Glen Canyon Dam, but continued for many years above Lees Ferry.

Unfortunately, Glen Canyon Dam radically altered the Colorado River and led to a host of new ecological problems. Water flowing through the Canyon is now much clearer than it was in the past, since a great deal of sediment is trapped behind the dam. The volume of water flowing through the river channel is much more even throughout the seasons than it was prior to the dam, and the water temperature generally stays around 40-50 degrees Fahrenheit, whereas before it fluctuated from near freezing to over 80 degrees.

These changes have had a dramatic impact on the ecology of the Colorado River. Clear water favors non-native fish species, scouring floods no longer clear the corridor of vegetation, and cottonwoods have trouble reproducing since they depend on floods to stimulate their seeds to sprout. In 1996, 2004, and 2008 the Bureau of Reclamation agreed to allow excess water from Lake Powell behind Glen Canyon Dam to flush the River in a controlled flood to help counter some of these ecological problems by mimicking natural seasonal floods. Scientists are still studying the results to see if this is a practice that should be continued regularly in the future.

Another ecological issue that has consumed the Park Service’s attention and budget for many years, and that is increasingly in the public eye, is that of forest health. In the 1920s and 1930s the NPS depended on cut, peel, and burn programs to attack insect infestations in the forested areas of the park. They transitioned in the 1940s to the newly developed toxic pesticides, including DDT, which made its appearance by 1953 when rangers sprayed a fifty-foot strip of aspens to kill tent caterpillars along the Point Imperial Road, reporting the treatment to be nearly 100 percent effective.

Introducing trout contributed to the decline and extirpation of native fish species. Today, park biologists are working to remove Rainbow Trout from Bright Angel Creek (fish weir, in photo) and have begun a program of electro-shocking trout and other invasive species from the Colorado River.

Photo: Michael F. Anderson

Battling insect infestations was among the work duties assigned to Civilian Conservation Corps laborers in the 1930s at Grand Canyon National Park. They used manual low-technology methods, shown in this photo, in the days before the widespread marketing of powerful chemical insecticides.

Photo: Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection.

Of course DDT turned out to be a notoriously toxic and persistent poison, about which Rachel Carson raised the alarm in her seminal 1963 book Silent Spring. The federal government eventually banned the use of DDT in the U.S. in 1972.

An unrelenting, escalating war on forest fires encompassed the entire park and adjacent forests, with administrators agreeing with Forest Service managers to report and suppress fires regardless of jurisdiction. From the 1920s through the 1950s, efforts to eliminate forest fires from the forested plateaus of Grand Canyon became increasingly concerted, costly, and sophisticated. Superintendent Harold Bryant was gratified in the early 1950s that fires burned an average of less than one acre in a thousand annually, unaware that achieving the decades-long goal of near-total suppression had radically altered forest ecology and created conditions for subsequent catastrophic high-intensity fires. NPS policy toward forest fires changed in 1978, when the park began to implement prescribed burns, but it will take decades and perhaps longer to reverse the ecological damage.

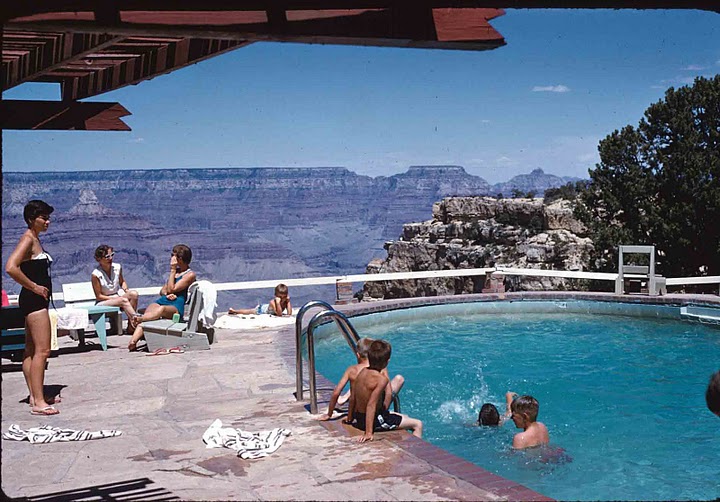

In the first decades of the twentieth century, government-employed biologists were on the cutting edge of ecological science. Then came World War II, federal budget cuts, and the end of many of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal conservation programs. Scientific research and the development of facilities for park visitors both languished in the 1940s and early 1950s. Ironically, this coincided with an unprecedented groundswell of American enthusiasm for outdoor recreation. Responding to visitor complaints of rundown and insufficient park accommodations, the Congress in 1956 authorized a ten-year, billion-dollar infrastructure improvement program labeled “Mission 66.” Embraced enthusiastically by the Park Service, this emphasis on roads, hotels, visitor centers, and other forms of tourist development ran up against awakening concerns for protecting the environment, inaugurating a Park Service-environmentalist rift that continues to this day. By the 1960s, environmentalists began to argue that the Park Service was practicing “façade” management, promoting scenery over ecological integrity. Americans still debate today whether national parks should primarily serve as pleasuring grounds for people or preserves where natural ecological processes take precedence over human desires.

Signal Hill Fire Tower at Pasture Wash, 1937. The Forest Service and Park Service employed a great deal of manpower and much money detecting and extinguishing forest fires as quickly as possible from 1893 through the 1970s. Since the latter years, park administrators have employed even more money and energy trying to re-establish a more natural fire regime, important to the health of Grand Canyon’s forests.

Photo: Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection

In reply to its critics in the 1960s, the Park Service promised to accelerate its ecological research programs, but at the same time it reaffirmed traditional park development patterns. Critics complained about park visitors as “invading locusts,” “tin can tourists,” and “irresponsible amusement seekers,” but in a policy letter to Interior Secretary Stewart Udall in 1961, Park Service Director Conrad Wirth wrote that national complaints over deteriorating park infrastructure and visitor facilities had “far outdistanced” complaints about overdevelopment, suggesting that citizens in a democracy should get what they desire from their parks. Seeking to harmonize visitor accommodation with nature preservation, Wirth reaffirmed a Park Service policy of maintaining “zones of civilization” where visitors would be concentrated rather than spreading out development in all areas of the park.

This strategy remains a useful tool in backcountry management even today. But Wirth could not silence critics who correctly pointed out that more and better facilities encouraged more use, which inevitably led to more crowds and greater impacts on wildlife and the environment. Many began lamenting that Americans were loving their parks to death.

The rise of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s prompted Congress to respond with an extraordinary proliferation of environmental protection laws, including the Wilderness Act, Endangered Species Act, Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, National Environmental Policy Act, and many others. These laws imposed real mandates on private industry and federal land managers, including the national parks, even though implementation was often piecemeal, underfunded, and resisted.

Despite the emphasis on providing facilities for visitors, park administrators also continued to seek remedies to environmental problems. For example, for most of the park’s history, nearly the entire Canyon was treated as open range subject only to loosely administered grazing permits and a cow’s ambitions. Poorly managed cattle and sheep grazing degraded vegetation and competed with native wildlife. Even the earliest park rangers could plainly see the damage that grazing was doing to the environment by destroying native plants and driving away native animals. When the Park Service sought to reduce grazing or require better management, local ranchers vociferously resisted. Well into the 1950s, the livestock industry successfully countered most efforts to regulate grazing in the park. But slowly and persistently, superintendents reduced stocking levels and improved range management to reduce the ecological impacts of grazing. Finally, in the mid-1980s, the last grazing permit in the park was retired, leaving the park’s forage entirely for native grazing animals like deer and elk.

While recent NPS management plans for Grand Canyon have eloquently articulated the need to protect natural conditions and native wildlife in the park, the 1995 General Management Plan continued to emphasize finding ways to allow still more people to enter the park. Ecological restoration projects are often mired in debates over cost, purpose, viability, and priority.

In many ways Canyon ecosystems have been changed beyond repair, such as the present state of the Colorado River as a result of the Glen Canyon Dam, and the tenacious and impossible-to-eradicate species such as cheatgrass and tumbleweed. Park rangers today take what actions they can to reduce the influence of non-native species with an eye towards restoring as much of the native ecosystem as possible. Organisms considered “pests,” such as ticks that threaten humans and beetles that kill trees, present another dilemma since they are components of the environment; therefore the NPS keeps ecological concerns in mind when using a careful evaluation system on a case-by-case basis to determine how to deal with such pests.

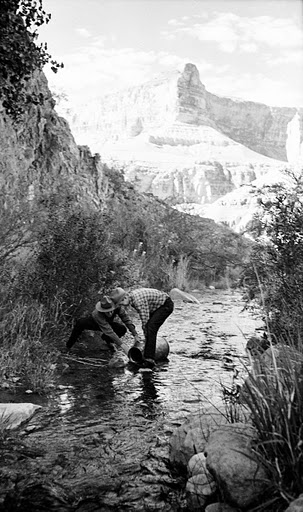

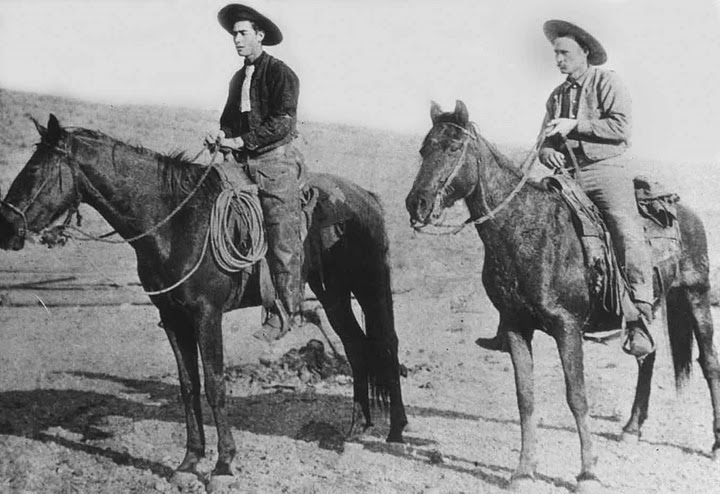

Two ranchers, Edward Lamb, Sr. and Taylor Button, at the North Rim, in 1892. Cattle ranged freely along the North and South Rims and within Grand Canyon before 1919. The Park Service’s long, arduous campaign to remove them from park bounds finally succeeded by 1985.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, Call No: NAU.PH.438-12

The Tuweep area of the Canyon is a desert scrub zone, in an area rarely traveled by humans. Though most of its native plant communities are largely intact, invasive plants are present in part due to past livestock grazing. In 2009, NPS rangers and volunteers began a program to remove invasive species from the area to help restore its native ecosystem.

Photo: NPS photo by Mike Quinn.

Development of the American West has always clashed with traditional Park Service goals to protect scenic assets as well as accommodate peoples’ ability to enjoy them. Special interests may argue which way policy should lean at Grand Canyon National Park, but no matter which path administrators choose they will be hampered by modern ecological issues their predecessors helped create, nearly all of which stem from regional population growth and its attendant development and pollution, or from the volume of annual visitors that has doubled in the last quarter century to nearly five million. Some issues are largely confined within park bounds and are easier to manage if not resolve to everyone’s satisfaction; others originate near and far outside the park, entail adjacent land, water, and air management agencies, are difficult to manage, and seemingly impossible to resolve to anyone’s satisfaction. One thing is certain: executing the National Park Service mission to provide for public enjoyment without impairing the park ecosystems is not as simple as it appeared in 1916.

Written By Micheal F. Anderson, Paul Hirt, and Sarah Bohl Gerke

Suggested Reading:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters, and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael F. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.

- Houk, Rose. An Introduction to Grand Canyon Ecology. Grand Canyon Association, 1996.

- Hughes, Donald J. In the House of Stone and Light: A Human History of the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1978.

- Krutch, Joseph Wood. Grand Canyon: Today and All its Yesterdays. New York: Doubleday, 1962.

- Sellars, Richard West. Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.