Searching for words

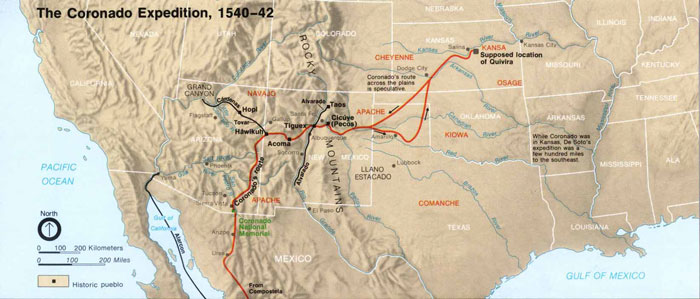

Spanish explorer Francisco Vázquez de Coronado traversed the modern American Southwest searching for the fabled Seven Cities of Gold. A side exploration led by García López de Cárdenas that bumped into the Grand Canyon did not consider it very noteworthy, though later it would become the source for many literary works.

Map: National Park Service

In 1540 a group of bedraggled men led by Captain García López de Cárdenas, part of the exploratory party led north from Mexico by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to seek out the legendary Seven Cities of Gold, became the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon. Cárdenas and his men spent several days on the Canyon rim trying to find a path down to the Colorado River. What grandiose and poetic language did Cárdenas use to describe this unusual and awe-inspiring landscape that has inspired generations of writers since? Well, in fact—he used none. A feature that today is considered one of the seven wonders of the natural world was mentioned only in passing by two subordinate members of the expedition.

Stephen Pyne in his book How the Canyon Became Grand argues that the culture of visitors to the Grand Canyon determines what makes the greatest impression on them, and this affects how they describe the Canyon to others, whether in writing, art, or photography. Cárdenas, looking for golden cities, saw the Canyon as little more than a wasteland and obstacle.

Since that time, however, as different cultures with different values and viewpoints have interacted with the Grand Canyon, many authors have been inspired to expend a great deal of poetry and prose trying to describe its colors, its forms, its allure, its mystery, and its meaning. In fact, with thousands of books written about it, the Grand Canyon has both shaped and been shaped by trends in American literature. Though the Canyon may have offered little in the way of extractable economic resources, it has provided a wealth of source material for authors and artists for over 150 years.

Centuries passed from the time of Cárdenas’s explorations until Euro-Americans began exploring the Canyon. In the meantime, Europeans and Euro-Americans developed an interest in travelogues and reports of expeditions in this age of exploration. As a result, future visitors to the canyon would see it and write about it from a different cultural perspective. As Stephen Pyne states, “from 1869 to 1882 it went from the status of a legendary giant suck to the subject of two classic works of American letters” (Pyne 1998: 38). These two works are Joseph Ives’ Report Upon the Colorado River of the West and John Wesley Powell’s The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons.

A lieutenant in the U.S. Army, Ives led the Colorado Exploring Expedition through the West in 1857-58. The group included a physician-naturalist, an artist, and a cartographer, all of whom contributed to the report of their travels published in 1861 with prose colored by the Romantic Movement in literature, which emphasized the aesthetic appreciation of nature and exaggerated emotionalism. Ives’ description of the Canyon relied heavily on comparisons with Egyptian landscapes of pyramids and obelisks; since only a handful of Europeans had seen the Canyon or anything like it before, there was little else that he could have compared it to that would have made sense to his audience.

Despite his vivid descriptions of the landscape, in the end, Ives concluded that the area was “altogether valueless” and predicted that his party would be the last Euro-Americans to ever visit the Grand Canyon. As he stated in his report, “It can be approached only from the south, and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed” (James 1910: 219).

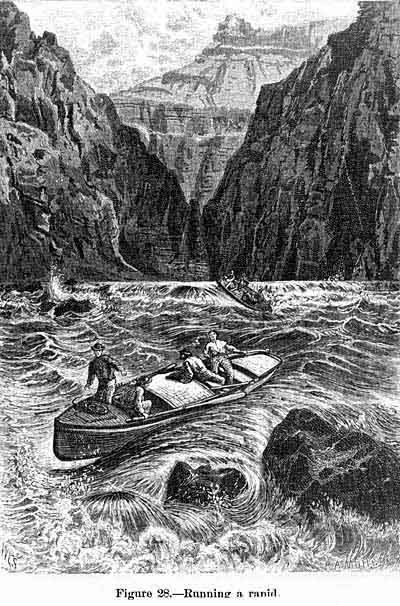

John Wesley Powell’s report of his journey was a bit different. In 1869 and again in 1871 he led an expedition of men in boats down the Colorado River, beginning at Green River, Utah and ending at the Grand Wash Cliffs at the western end of the Grand Canyon. His journal of the expedition was first published in 1872 as The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons. It was a journey into a great blank spot on the map of America: “We have an unknown distance yet to run; an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not” (Powell 1961: 274).

Powell’s published journal described the terrain, geology, vegetation, Native American inhabitants, dangerous rapids, and the trials and tribulations of the men on the expedition. Though it was intended as a scientific report, it was written as an adventure tale, thus showing the influence of both the beginnings of a late-19th century scientific revolution and Romanticism. This action-packed book allowed readers to vicariously experience true-life escapades, and even today readers are enthralled by Powell’s accounts of the Canyon and his journey through it. As Stephen Pyne states, “His personal narrative created the classic expression of the view from the river, the words by which his generation appreciated its revelation, the images by which tourists throughout the twentieth century have understood it” (Pyne 1998: 57-58).

William Henry Holmes provided the illustrations for Clarence Dutton’s Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District. Like Dutton’s writing, Holmes’s artwork helped combine science and aesthetics through his precision and details as well as his appreciation of the Canyon’s beauty.

Photo: Sheet XV – Panorama from Point Sublime by William Henry Holmes. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

“The Grand Cañon of the Colorado is a great innovation in modern ideas of scenery, and in our conceptions of the grandeur, beauty, and power of nature. As with all great innovations it is not to be comprehended in a day or a week, nor even in a month. It must be dwelt upon and studied, and the study must comprise the slow acquisition of the meaning and spirit of that marvelous scenery which characterizes the Plateau Country, and of which the great chasm is the superlative manifestation.”

– Clarence Dutton, 1882

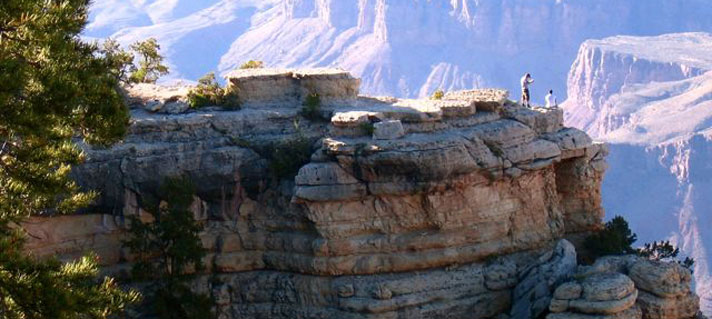

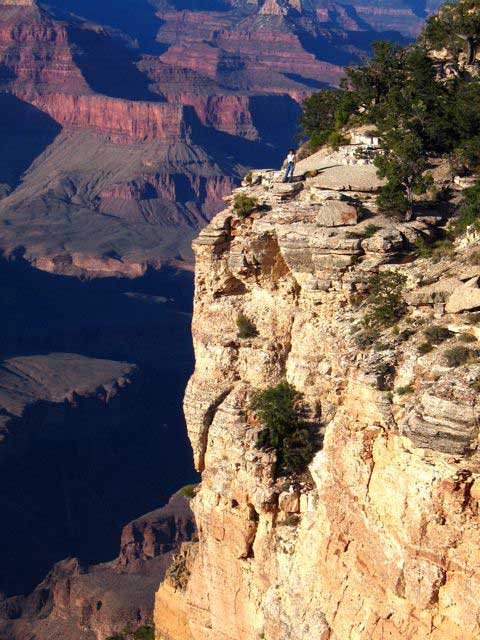

Photo: Paul Hirt

One of the most comprehensive literary works about the Grand Canyon appeared just a few years later. In 1882 Clarence Dutton published his Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, a book that combined geology, cartography, painting, photography, literature, and philosophy to create a masterpiece of late 19th century scientific, cultural and artistic studies of the Grand Canyon. While Powell told the story of the Canyon as experienced from the Colorado River, Dutton told his story of the Grand Canyon from the rim. Because most visitors only see the Grand Canyon from the rim, Dutton’s descriptions resonated for tourists through the next century. He framed his work as an epic geologic history, combining his skills at writing with his enthusiasm for science, in the process making the science of the Canyon accessible while also bringing a new artistic appreciation to it.

The Grand Canyon made a broader contribution to American literature most noticeably around the turn of the twentieth century, when travel writing became popular. By the late 1880s, tourists had begun visiting the Canyon, and writings about it consequently became more popular, in both senses of the word. At this time, the area was still hard to reach, so the trip to the Canyon was almost as interesting as the Canyon itself, giving visitors a sense of discovery that often comes through in their writings. Prose in this late Victorian/early Modernist era is known for its overt emotional and embellished style, and the Grand Canyon was a site where travel writers could indulge their passion for flowery language to a high degree.

These descriptions in turn encouraged more visitors and writers to experience the Canyon and offer their own literary expressions. For example, in 1897 two young sisters from Brooklyn, New York, Amelia and Josephine Hollenback, traveled throughout the Southwest, taking pictures, keeping diaries, and writing letters home describing their journey, the people they met, and the places they saw.

They arrived at the Grand Canyon via an all-day bumpy, dusty stagecoach ride from Flagstaff. Amelia Hollenback quickly grew to love the Canyon, writing that “…night after night the colors changed to new beauty and the Canon grew from an awful forbidding realm of another planet to a kind of protecting presence, grander and more beautiful but no longer oppressive. Sometimes I think that a person might feel safer here than in any other place on earth. It seems too calm, too great for any of the harms and bothers that vex the outside world to live near the shining of its walls” (Cook 2002).

“There are many-colored rock fragments strewed around, and wild flowers and cacti, sage brush and queer twisted cedars and pinons grow all about. Perhaps if you stood on those rocks just ahead you might see better which way to go. You try it,–and then you see IT! As if half the world had fallen away before your feet, and after that you are no longer on the same old earth.”

– Amelia Hollenback, 1897

Photo: Paul Hirt

“Here, indeed, is the idea of the pagoda architecture, of the terrace architecture, of the bizarre constructions which rise with projecting buttresses, rows of pillars, recesses, battlements, esplanades, and low walls, hanging gardens, and truncated pinnacles”

– Charles Dudley Warner, 1891

Photo: Paul Hirt

One of the premier travel writers of the late 19th century was Charles Dudley Warner, who became the first noted author to publicize the Grand Canyon as a tourist destination when he wrote “The Heart of the Desert” in 1891. Warner described in depth the colors of the rocks, and compared the landforms to “Oriental” buildings, stating that “here, indeed, is the idea of the pagoda architecture, of the terrace architecture, of the bizarre constructions which rise with projecting buttresses, rows of pillars, recesses, battlements, esplanades, and low walls, hanging gardens, and truncated pinnacles” (Schullery 1981: 43).

George Wharton James would expand on this foundation by publishing two books, In and Around the Grand Canyon (1900) and The Grand Canyon of Arizona: How to See It (1910), making him one of the more famous figures in Grand Canyon literature. To gather information for his books James had traveled along a great deal of the Canyon, from Cataract (or Havasu) Canyon and W.W. Bass’s camp on the western edge to Lee’s Ferry in the east, over a period of 10 years. Unlike previous works, these were written primarily for people who were planning to visit the Canyon to see it with their own eyes. In the first, he gives a history of the Canyon and describes its many trails. In the latter book he gives readers descriptions of different areas of the Grand Canyon from El Tovar to Grandview Trail and offers advice on how to best spend their time. He includes information about the larger Grand Canyon region and how to see it as well, including quite a bit of information on local Native American tribes.

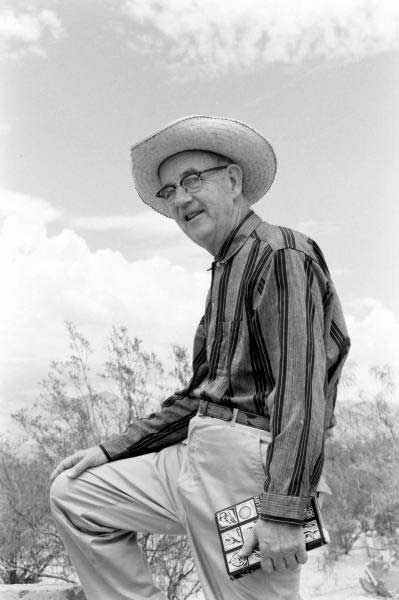

“I have seen strong men fall upon their knees. I have seen women, driven up to the rim unexpectedly, lean away from the Canyon, the whole countenance an index of the terror felt within, gasp for breath, and though almost paralyzed by their dread of the indescribable abyss, refuse either to close their eyes or turn them away from it.”

– George Wharton James, 1910 (at left in photo)

Photo: NAU.PH.96.3.23.8. Lauzon Family Collection. Cline Library, NAU.

“For surely it was not our world, this stupendous, adorable vision. Not for human needs was it fashioned, but for the abode of gods. It made a coward of me; I shrank and shut my eyes, and felt crushed and beaten under the intolerable burden of the flesh. For humanity intruded here.”

– Harriet Monroe, 1899

Photo: Paul Hirt

The variety of viewpoints and approaches to writing about the Canyon at this time expanded into many different genres. Poet-essayist Harriet Monroe of Chicago in 1899 wrote about the Canyon from a Victorian woman’s perspective. She describes in somewhat histrionic language her feelings of not being strong enough to see what awaited her at the rim of the Canyon, and of the sensation that she was standing at the edge of the world when at the rim. However, she passionately called for the Canyon’s preservation, even arguing that in the future tourists should be prohibited since she believed that humanity only intruded there.

Famed early environmentalist John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, wrote eloquently about the Grand Canyon’s “wild, primeval beauty and power” in a 1902 article entitled “Our Grand Canyon.” He was especially enamored of color and light and prone to ecstatic expressions when confronting such sublime spectacles as a Canyon sunset: “But the colors, the living, rejoicing colors, chanting morning and evening to heaven! Whose brush or pencil, however lovingly inspired, can give us these? And if paint is of no effect, what hope lies in pen-work? Only this: some may be incited by it to go and see for themselves” (Schullery 1981: 73).

Art historians and critics such as John Charles Van Dyke similarly believed that the canyon could never adequately be captured by pen or brush: “The great chasm cannot be successfully exploited commercially or artistically. It cannot be ploughed or plotted or poeticized or painted. It is too big for one to do more than creep along the rim and wonder over it. Perhaps that is not cause for lamentation. Some things should be beyond us – aspired to but never attained.” (Van Dyke 1920: 218).

Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Hamlin Garland in 1902 wrote an essay about two phases of the Canyon, one during the day and the other at nighttime. He penned from the bottom of the Canyon: “It is worth while to spend a night alone among these prodigious peaks and listen to the voice of the Colorado as it roars with ever-increasing power, like some imperious nocturnal animal—a dragon with a lion’s throat. As the shadows deepen in the lower deeps, beginning to wash like the flood of a spectral purple sea the gray-green mesas of the lower levels, then the river’s voice swells till it seems to fill the whole enormous canyon—savage, solemn, and persistent.” He concludes at the end of his essay about the Canyon, “I began to understand that it had a thousand differing moods, and that no one can know it for what it is who has not lived with it every day of the year…The traveler who goes out to the edge and peers into the great abyss sees but one phase out of hundreds” (Garland 1902: 61-62).

Taking a different tone than most authors describing the Grand Canyon, along the lines of Mark Twain, Irvin Cobb, a humorist for the Saturday Evening Post, recorded his observations about the canyon and his fellow tourists in a comic piece called “Roughing It De Luxe.” As Cobb drolly wrote, “It is generally conceded that the Grand Canon of Arizona beggars description. I shall therefore endeavor to refrain from doing so. I realize this is going to be a considerable contract. Nearly everybody, on taking a first look at the Grand Canon, comes right out and admits its wonders are absolutely indescribable—and then proceeds to write anywhere from two thousand to fifty thousand words, giving the full details. Speaking personally, I wish to say that I do not know anybody who has yet succeeded in getting away with the job” (Cobb 1913: 15).

Ellsworth Kolb and his brother Emery, who ran a photography studio at the Grand Canyon from 1902 to 1976, traveled the entire length of the Colorado River in 1911. They filmed a motion picture of their exploits, and Ellsworth later wrote a widely-distributed photograph-heavy book about the experience titled Through the Grand Canyon from Wyoming to Mexico. The introduction to the book was written by Owen Wister, who is largely credited with inventing the cowboy-western genre with his novel The Virginian. Impressions of the canyon and river as experienced during rafting or boating trips down the Colorado River have increasingly become a source of inspiration for literary works about the Grand Canyon, such as Kathleen Ryan’s Writing Down the River, Patricia McCairen’s Canyon Solitude: A Woman’s Solo River Journey Through the Grand Canyon, or Welch, Conley, and Dimock’s Doing the Thing: The Brief, Brilliant Whitewater Career of Buzz Holmstrom.

The mystery and grand scope of the Canyon inspired writers to concoct fictional stories as well. For example, in 1910 James Paul Kelly produced Prince Izon: A Romance of the Grand Canyon. The preface describes the Canyon as dangerous yet mysterious and alluring, depicting it as an alien or hellish landscape that is also somehow like paradise. In the story, an archeology professor, his niece, and her friend discover ancient Aztec cities in an unexplored side canyon, presided over by the ancestor of Montezuma, the eponymous Prince Izon. The Grand Canyon is merely a backdrop to the tale of melodramatic romance and adventure.

Ellsworth Kolb wrote a book about his experience traveling down the Colorado River with his brother in 1911 that sparked the imagination of future generations of river runners. This photo from that book shows how they had to carefully pack everything, including their cameras and motion picture film equipment, to guard against water damage.

Photo: NAU.PH.568.3434. Kolb Brothers Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

Many other works of fiction contain references to the Grand Canyon. For instance, American folk hero Paul Bunyan is supposed to have created the Grand Canyon when he dragged his axe behind him. Western writer Zane Grey’s experiences at the Grand Canyon inspired him to mention the landscape in several of his works, including Roping Lions in Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon has also been the setting for several recent Harlequin romances written by women authors such as Anne Marie Duquette, Patricia Chandler, and Ann Collins. As a reflection of modern times, a 2007 novel by Gary Hansen tells the fictional story of a government employee hunting down an environmental terrorist in a plot that takes readers from Lake Powell through the Grand Canyon to the mouth of the Colorado River in Mexico.

Burros were commonly used at the Grand Canyon at the turn of the century to haul people and goods. One such burro provided the inspiration for Marguerite Henry’s popular children’s book Brighty of the Grand Canyon.

Photo: NAU.PH.90.15.15. F.H. Maude Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

Not only has the Grand Canyon influenced American literature, but literature has even had a tangible effect on NPS policies at the Grand Canyon. In 1953 Marguerite Henry wrote the Newberry Award-winning children’s book Brighty of the Grand Canyon, a story about an independent-minded burro’s life at the Grand Canyon around the turn of the century. Brighty befriends miners, park rangers, and campers in his adventures, and at the same time delights in the natural beauty of the Canyon. Disney later adapted the book into a movie.

Around this time, there was a growing crisis at the Canyon as a large population of feral burros, the progeny of miners’ burros that had escaped or been left behind when the prospectors moved on, began devastating native plants, polluting water sources, and driving away indigenous animals. Marguerite Henry’s book romanticized burros and led to a public outcry against the practice of shooting feral burros despite the problems they were causing, an outcry to which the NPS acquiesced.

Joseph Wood Krutch’s 1958 work Grand Canyon: Today and All Its Yesterdays is a more recent yet still romantic look at the natural history of the Canyon. Later turned into a successful television documentary, it helped mark a new generation of environmentalist writers including Wallace Stegner in a tradition reaching back to the likes of Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and Aldo Leopold. In fact, just a few years prior Stegner published Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, a book that would soon become a classic work of biography, history, and western literature. Though focusing on Powell, it also once again drew popular attention to the Grand Canyon by providing an entertaining narrative of how the Canyon had been explored, named, and enmeshed in American culture.

Krutch’s sentimental look at the Grand Canyon encouraged readers to see it as a wilderness with the capacity to reinvigorate the human spirit. Both Krutch and Stegner argued in their works for the preservation of this landscape, or more specifically, protection from rapacious development that was characteristic of the post-WWII period.

“The river carries us swiftly into the Granite Gorge. Like a tunnel of love, there are no shores or beaches in here. The burnished and river-sculptured rocks rise sheer from the water’s edge, cutting off all view of the higher cliffs, all of the outer and upper world but a winding column of blue sky. We glide along as in a gigantic millstream.”

– Edward Abbey, 1977

Photo: Yolonda Youngs

This theme spoke to many in the early environmental movement, and influenced subsequent authors in their writings about the Grand Canyon area, particularly Edward Abbey, the author of the provocative 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang. Abbey took a raft trip down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in the 1970s and kept a journal, portions of which were published in his 1977 book The Hidden Canyon: A River Journey.

Krutch and Abbey tended to portray the landscape as a pure wilderness, dismissing the long history of Native American and Euro-American settlement in the area. For example, Krutch states that “Despite all these living things so obviously at home here, there is absolutely no sign from which I would be able to deduce that any man besides myself had ever been here or, for that matter, that he had ever existed at all” (Krutch 1958: 9).

Literature about surrounding Native American tribes has existed for decades, though most were told from a Euro-American perspective. For example, Flora Gregg Iliff wrote about her experiences as a teacher on the Hualapai and Havasupai reservations at the turn of the twentieth century in her book People of the Blue Water: A Record of Life Among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians. Though the title implies that it is a book about the tribes, most of the book tells of the culture clashes she experienced solely from her Euro-American cultural point of view.

A more balanced interpretation came with anthropologist Stephen Hirst’s 1976 book, recently re-released under the new title I Am the Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People, which gives a comprehensive history of the tribe and their connection to the Grand Canyon.

More recently, some Native Americans, such as Havasupais Juan Sinyella and Rex Tilousi, have had their own essays that describe their tribe’s traditions and history appear in journals. Reports and essays outlining the relationship of Native Americans to the Grand Canyon and recounting their stories about the chasm are also beginning to appear more frequently. For example, T.J. Ferguson compiled a report, with the help of Hopi elders, entitled Öngtupqa niqw Pisisvayu (Salt Canyon and the Colorado River): The Hopi People and the Grand Canyon. This report, published by the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, detailed the Hopi ethnohistory of the Canyon. The Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department produced a similar report entitled Bits’íís Ninéézi (The River of Neverending Life); Navajo history and cultural resources of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, as did the Southern Paiute tribe under the title Piapaxa ‘Uipi’ (Big River Canyon).

Today, there are thousands of books, poems, essays, reports, and other literature available for readers of all levels that describe many different aspects of nature, culture, and history at the Grand Canyon. It is likely that people will continue attempting to convey the Grand Canyon experience in words, yet no one will ever truly capture it completely, since the way we describe the Grand Canyon is a reflection of our own language, times, surroundings, interests, biases, hopes, dreams and realities. As the Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet Carl Sandburg put it: “Each man sees himself in the Grand Canyon” (Sandburg 2003: 434).

Yet, as much as the Grand Canyon experience is individualistic, reflecting the unique perspective of each visitor, it is also collective. The Grand Canyon is a cultural landscape shaped and interpreted by a nation seeking to express its identity and values. What the Grand Canyon has been and has become reflects what the United States of America has been and become. In a nation consummately committed to material advancement, to having and consuming, to the desires of the present moment, national parks and preserves express a broader ethic, a commitment to protect sources of great national and cultural significance.

As Joseph Wood Krutch remarked half a century ago about the Grand Canyon: “The generation now living may very well be that which will make the irrevocable decision whether or not America will continue to be for centuries to come the one great nation which had the foresight to preserve an important part of its heritage. If we do not preserve it, then we shall have diminished by just that much the unique privilege of being an American” (Krutch 1958: 276).

Time has shown that America is not unique in its desire to preserve its natural heritage, although it set many important precedents and remains a leader in the global nature protection movement. Time likewise has shown that rather than a single moment of truth and consequences, our human relationship with nature at the Grand Canyon constantly evolves. We make and re-make our built and preserved landscapes continuously. The Grand Canyon reveals anew for every generation the complex relationship between nature and culture. And each generation will have its own literary voices to reflect upon that relationship.

For a searchable database of the over 34,000 works that reference the Grand Canyon, visit the bibliography housed at the Grand Canyon Association’s website: http://www.grandcanyon.org/bibliography.asp.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke and Paul Hirt

References:

- Anderson, Michael, ed. A Gathering of Grand Canyon Historians. Proceedings of the Inaugural Grand Canyon History Symposium, January 2002. GCA, 2005.

- Cobb, Irvin S. Roughing It De Luxe. Philadelphia: The Curtis Publishing Company, 1913.

- Condie, LeRoy. White Horse: A Story of the Grand Canyon. Santa Fe: Division of Indian Education, New Mexico State Department of Education, 1980.

- Cook, Mary J. Straw, ed. Immortal Summer: A Victorian Woman’s Travels in the Southwest. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2002.

- Dutton, Clarence. Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2001.

- Ferguson, T.J. Öngtupqa niqw Pisisvayu (Salt Canyon and the Colorado River); the Hopi People and the Grand Canyon. Final ethnohistoric report for the Hopi Glen Canyon Environmental Studies Project. Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, 1998.

- Garland, Hamlin. “The Grand Canyon at Night,” in The Grand Canyon of Arizona: Being a Book of Words from Many Pens, About the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona. Passenger Department of the Santa Fe, 1902.

- Henry, Marguerite. Brighty of the Grand Canyon. Rand McNally, 1953.

- Hirst, Stephen. I Am the Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People. Grand Canyon Association, 2007.

- Iliff, Flora Gregg. People of the Blue Water: My Adventures Among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1954.

- Ives, Joseph Christmas. Report Upon the Colorado River of the West. Anne Arbor: Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library, 2006.

- James, George Wharton. In and Around the Grand Canyon. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1900.

- James, George Wharton. The Grand Canyon of Arizona: How to See It. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1910.

- Kelly, James Paul. Prince Izon: A Romance of the Grand Canyon. Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co, 1910.

- Kolb, Ellsworth. Through the Grand Canyon from Wyoming to Mexico. Grand Canyon Association, 2007.

- Krutch, Joseph Wood. The Grand Canyon: Today and All Its Yesterdays. New York: William Sloan Associates, 1958.

- Powell, John Wesley. The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons. New York: Dover, 1961.

- Pyne, Stephen J. How the Canyon Became Grand: A Short History. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Roberts, Alexa, Richard M. Begay, Klara B. Kelley, Alfred W. Yazzie, and John R. Thomas. Bits’íís Ninéézi (The River of Neverending Life); Navajo history and cultural resources of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River. Window Rock, AZ: Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department, 1995.

- Sandburg, Carl. The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003.

- Schullery, Paul. The Grand Canyon: Early Impressions. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1981.

- Sinyella, Juan. “Havasupai Traditions.” Southwest Folklore 1 (Spring 1977): 35-52.

- Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. Penguin: 1992.

- Stoffle, Richard W.; David B. Halmo, Michael Evans, and Diane Austin. Piapaxa ‘Uipi (Big River Canyon). Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, 1994.

- Tilousi, Rex. “Hav’suw Ba’aja: Guardians of the Grand Canyon—Past, Present, and Future.” Wicazo Sa Review 9(2)(Autumn 1993): 62-69.

- Van Dyke, John Charles. The Grand Canyon of the Colorado: Recurrent Studies in Impressions and Appearances. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920.