Phantom Ranch is a place where nature, culture, and history mingle deep in the heart of the Grand Canyon.

Trails from the North and South Rim meet here. The only two bridges across the Colorado River for hundreds of miles span across the gorge near Bright Angel Creek. Hikers, river runners, and mule trains carrying riders and supplies all converge here as they journey through the canyon. The clear, cool waters of Bright Angel Creek cascade down the north side of the canyon bringing rock and debris that fans out into a large delta along the Colorado River. Ancestral Puebloan people called this area home, hunting and farming at this place in the canyon. Nestled in a small cluster of cottonwoods lies a historic tourist camp that has drawn visitors from around the world to relax near the little stone cabins designed by one of the most prolific and important architects in Grand Canyon history.

Phantom Ranch is a crossroads, with many stories to tell.

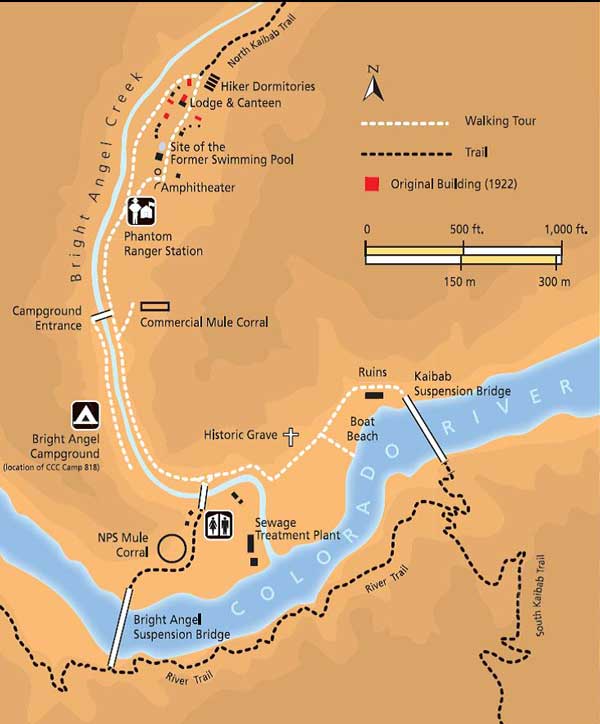

Phantom Ranch is a cluster of buildings, trails, and historic sites tucked into Bright Angel Canyon—one of the most important drainages in the Grand Canyon. It has a perennial stream fed by Roaring Springs at the headwall of the canyon and supports trees, plants, and soothing shade in this otherwise parched, exposed landscape. There is much to explore here. Take a moment to orient yourself to the area with this map. Most of the Phantom Ranch complex is north and west of the Colorado River. In this tour, we will explore the area in three sections—along the river, at the delta of Bright Angel Creek, and farther up the canyon at the Phantom Ranch guest area.

Arriving at Phantom Ranch is no easy feat. It is located at nearly 4,600 feet below the South Rim and can only be accessed by foot, mule, or boat. The South Kaibab and River Trail provide mule and hiker access to the Inner Canyon from the South Rim while the North Kaibab Trail provides access from the North Rim.

The Kaibab Suspension (Black) Bridge and the Bright Angel (Silver) Suspension Bridge offer hikers and mule trains connections between the north and south sides of the canyon. River runners may stop at the boater’s beach as a lunch spot or a place to mingle with other inner canyon visitors before continuing to head downstream.

Hiking along the North Kaibab Trail, just a few meters to the north of the Kaibab Suspension Bridge, between the trail and the Colorado River, you may notice a few stone walls and what looks to be the ruins of a house with many rooms. The red and brown rocks of differing sizes are cobbled together to form partial walls, somewhat hidden in the side of the bank facing the river by low lying prickly pear cacti, a scattering of desert brittle brush, and a few grasses. These are the remains of an indigenous pueblo site dating from A.D. 1050 to A.D. 1140. Thirty to forty Hisatsinom families—the name used by the Hopi, descendants of this Puebloan people—once called this site home, using this inner canyon oasis to hunt and farm.

While the canyon may look like a desert with little food or materials for housing, a closer look reveals a much different picture. Early farmers in the canyon used native vegetation such as agave and cacti as food sources. Today agave roasting pits may be found throughout the canyon, particularly along the Colorado River Corridor. With the populations of deer and bighorn sheep, hunting also provided a good source of food and resources.

On one of the Great Surveys of the West—large expeditions that set out to map, explore, and collect information about the western territories for the rapidly expanding United States—the expedition leader, John Wesley Powell and his crew encountered a cool clear stream coming out of a side canyon.

Contrary to the modern version of the Colorado River—a jade colored river with temperatures hovering in the high 60s—the Colorado River that Powell encountered was warm and silt laden. He and his men were happy to find the clear waters of Bright Angel Creek coursing out of a side canyon, offering a welcome reprieve from the muddy waters they had been drinking and floating on for weeks.

In his first journal from his 1869 expedition down the Colorado River, Powell referred to this stream as Silver Creek. “The little affluent which we have discovered here is a clear, beautiful creek, or river, as it would be termed in this western country, where streams are not abundant.” In his later account of the trip, he changed the name to Bright Angel Creek, a contrast to the Dirty Devil River the crew encountered upstream earlier in the journey. The aridity of the west was not lost on Powell. His two journeys through the Grand Canyon and down the Colorado River (in 1869 and then again in 1871) convinced Powell that water was a key to settlement and economic development of the American West.

The building materials for this ruin come from the rock walls surrounding you here in the Inner Gorge. The distinctive cliff-slope-bench profile formed in sedimentary rock layers that you can see from the rim of the canyon abruptly changes shape here. Dark walls of older Precambrian rocks—shaped by heat and pressure as metamorphic and igneous rocks—dominate the inner canyon scene. The deep gray and black of the Vishnu Schist forms the high walls of the Inner Canyon. Veins of red Zoroaster Granite in the schist run through these walls. Other notable deposits you’ll see in this area are deep red Hakatai Shale and Bass Limestone. Can you pick out any of these rocks in the walls of the ruins?

Photo: Yolonda Youngs.

The vegetation in the canyon varies more than one might think given the park’s desert location. There are 129 distinct vegetation communities in the Grand Canyon. The types and distribution of the plant communities in the canyon depend on a combination of factors including the elevation, climate, soil, and slope aspect (the angle and direction that sun hits the surface).

Near the Kaibab Bridge you will see a mingling of at least two vegetation communities—the desert scrub and the riparian community. At this low elevation in the canyon, the vegetation is a mixture of plant varieties from the arid desert scrub community (seen around the ruins) and a riparian community (closer to the river). Near the ruins you will see brittlebush, beavertail, prickly pear, and hedgehog cacti, and a few large tamarisk shrubs. Closer to the river, the tamarisk covers most of the bank

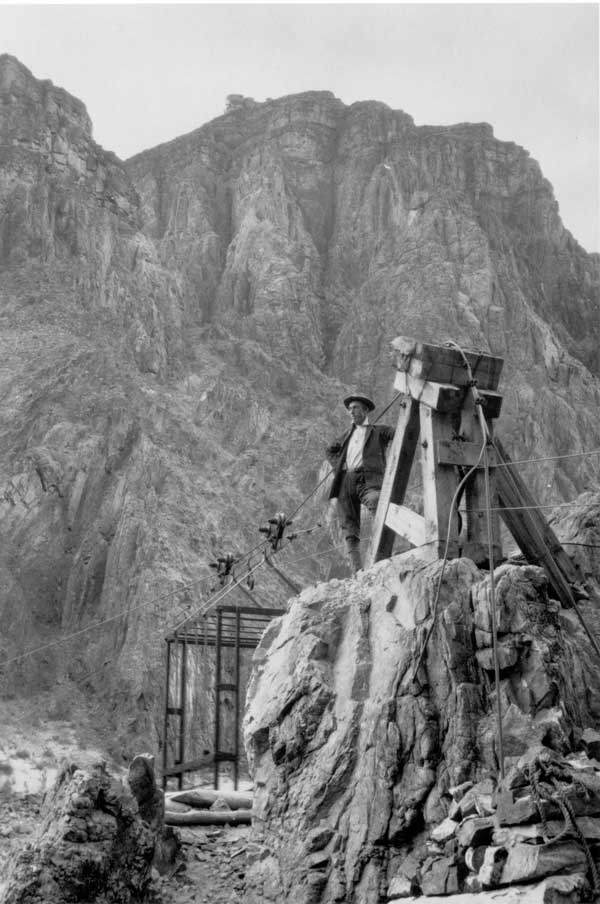

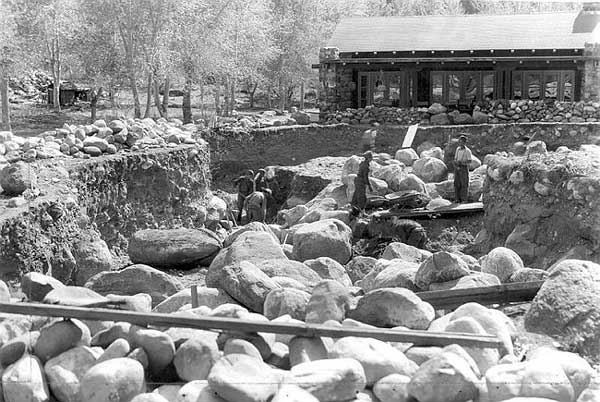

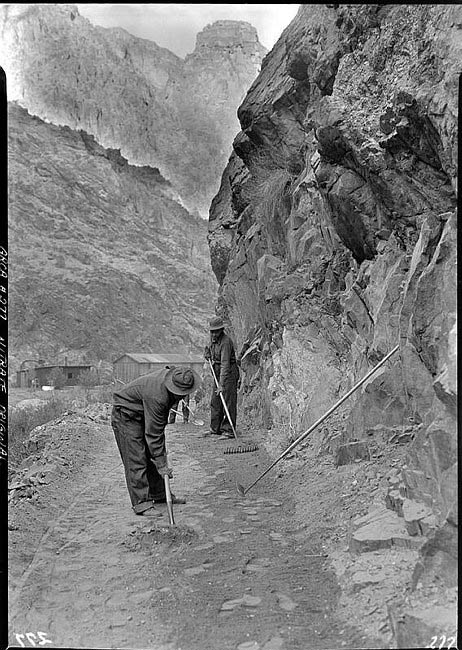

The Great Depression meant economically hard times around the country but it had an unexpectedly positive and lasting impact on America’s national parks. The Grand Canyon, like many national parks around the country, had fewer visitors entering the park during those years. During this time, the much of the park infrastructure—the often overlooked but essential features of park landscapes such as trails, roads, and power systems—received considerable upgrades and improvements through the hard work of young men in the Civilian Conservation Corps. As a national federal relief project, CCC “camps” were established in Grand Canyon National Park to house these young workers. Many of the park trails, roads, and visitor service features we use today were built by these young men through skilled workmanship and hard labor.

In the Inner Gorge of the Grand Canyon near Phantom Ranch, the CCC Camp #818 was located on the present site of today’s Bright Angel Campground. From this base, young men worked during the winter when temperatures were relatively mild compared to the wintry conditions on the forested rims. In the hotter summer months, they moved to the rim. CCC workers built the River Trail along the Colorado River, blasting a ledge for the trail into the rock wall. They also improved many other trails, built several buildings around Phantom Ranch, and the first trans-canyon telephone line. The work was difficult and often dangerous. While most Grand Canyon pioneers and significant personalities are buried at the South Rim cemetery near the Shrine of Ages the marked grave site near the Kaibab Suspension Bridge is an exception. Near the ancestral Puebloan ruins site to the north of the Kaibab Suspension Bridge lies the grave of Rees Griffiths–a trail crew foreman killed by rock fall in 1922 (Thybony, S. 2001).

Much of the infrastructure was built and improved through the federal works program in the 1930s known as the Civilian Conservation Corps. Young men from around the country came to the Grand Canyon to build trails, fire lookout towers, pipelines, and more.

Photo: Grand Canyon NP Museum Collection NPS #00277

The boat beach is a regular stop for groups traveling in boats of all shapes, sizes, and propulsion. This images depicts a few varieties of boats commonly found in the canyon—oar rigs (inflatable rafts, yellow), wooden dories (white and red boats), and motor rigs (large blue boats).

Photo: Yolonda Youngs

By mid morning in the summer months, as the inner canyon gets its daily dose of sunshine peaking over the tall walls of the canyon, the area around Bright Angel Creek is bustling with activity at this meeting ground in the depths of the Grand Canyon. Boating, mule riding, and hiking are the only ways to reach this inner canyon area. Hikers arriving from the rim descend into the canyon on the South and North Kaibab Trails. Mule trains loaded with saddle sore tourists and supplies for the Phantom Ranch complex cross the Kaibab Suspension Bridge on their way across the river.

A few yards just below the ruins site there is a large sandy beach that is a popular resting spot for commercial and private river trips. Sitting along the trail near the ruins for a few hours during a summer afternoon is great entertainment. Here, you will see successive flotillas of boats in all shapes and sizes push up to the beach and unload their passengers. The boaters arrive at the beach—a sandy spit of land that is part of the Bright Angel Delta—to park their boats, hike up to Phantom Ranch, mail letters and postcards, exchange passengers, and take a lunch break from their journey downstream. The next section of river holds some of the largest and most challenging rapids in the canyon; it is best to get a good meal and stretch your legs before this part of the adventure.

Traveling down the river from the put-in at Lee’s Ferry to a typical take-out at Diamond Creek can take from 7 days by motor boat up to 3 weeks by oar powered rig (inflatable raft or wooden dory). Some passengers choose to hike out of the canyon at this point, ending their river journey, while other passengers join the trip by hiking down the canyon to meet a boating party.

Contemporary boating parties cannot camp at the beach—the popularity of this beach and the high numbers of boating parties pushed the National Park Service to regulate this site for impact and use—early river runners enjoyed the respite here. The boater’s beach offered a few days of respite for the tired and travel weary men of John Wesley Powell’s 1869 expedition along the Colorado River (Powell, 1895 and Thybony 2001).

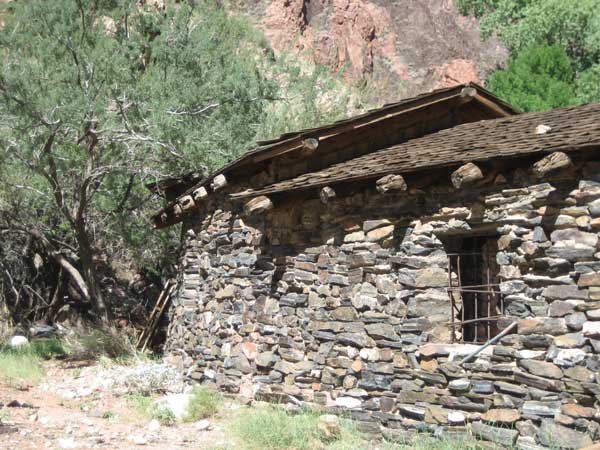

Between Bright Angel Creek and the Bright Angel Suspension Bridge a small group of structures are tucked in the cool shade of tamarisk trees, shrubs, and grasses where the Bright Angel Creek spills out into this delta. Most of the structures in this area are service buildings or support structures for National Park Service rangers. You will pass through this area on your way from the Bright Angel Bridge to Phantom Ranch. Some of the structures here date from the 1920s such as an operator cabin (1922) and an NPS staff cabin called the Rock House (1926). Other buildings were crafted through the skills and labor of CCC workers in the 1930s—the NPS mule corral (1935), the River Ranger Station (1934), and Rock House Bridge (1936) (Anderson 1998, 149). A sewage plant and restroom facility (constructed here in 1981) also sit at this location; they are essential elements of this working landscape, one that is needed to maintain sanitation at Phantom Ranch which hosts thousands of visitors every year (Powell, 1895 and Thybony 2001).

CCC camp #818 was the winter home of workers who crafted many of the stone and wood structures you see at Phantom Ranch today. Along with the NPS mule corral and nearby structures, the CCC also built bridges, a cross canyon telephone line, and a swimming pool near the cantina of Phantom Ranch.

Bright Angel Campground is a popular and scenic spot to rest for the night. Originally established as Camp #818 for CCC workers, the campground now hosts up to 90 backpackers per night along the Bright Angel Creek. The campground is a popular spot for hikers traveling from rim to rim through the canyon or for those just wishing to visit the Inner Canyon along the North Kaibab Trail.

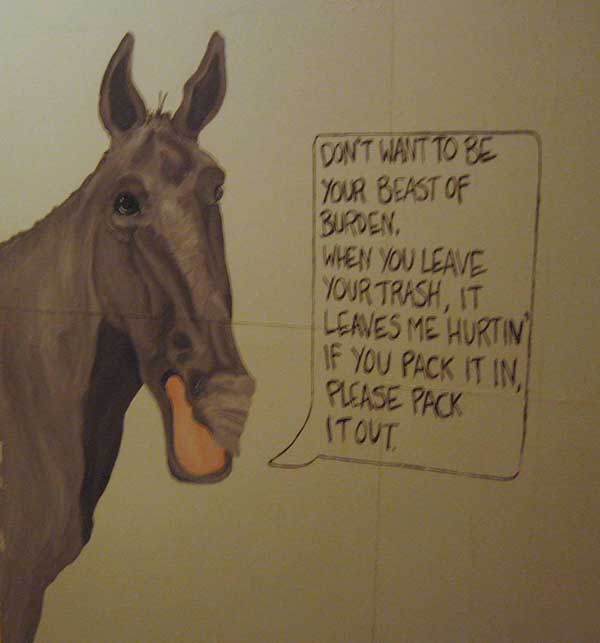

Mules carry all the food, equipment, and many of the people in and out of the canyon. A trip down to Phantom Ranch by mule is considered by some to be the quintessential Grand Canyon experience. Popularized by books such as Brighty of the Grand Canyon (1953) by Marguerite Henry and movies, the mules of the Grand Canyon are an essential transportation and recreation connection between the rim and the inner canyon.

The ride down to Phantom Ranch by mule takes a full day and requires reservations months before the trip is taken. The mules carry more than tourists, though. They also carry all of the supplies needed to keep Phantom Ranch as a working guest resort. From food into the canyon to trash out of the canyon, Phantom Ranch relies on the daily efforts of mule wranglers and the mules to make the ranch work.

Although the Grand Canyon is an area defined by aridity, an environmental factor that affects everything from the plants, animals, and birds you see that are adapted to these low moisture conditions and high temperatures, it does have occasional streams and waterfalls that support a more lush display of vegetation. Phantom Ranch is rare though, in that it is a desert oasis. Canyon wildlife is drawn to this place.

If you hiked or rode a mule down the canyon to visit this spot, you no doubt noticed the change in temperature as you descended the trail. The Grand Canyon is an inverted mountain in this respect; temperatures at the rim—between 8,000 and 7,000 feet in elevation—are typically much cooler than temperatures at the bottom of the canyon. The cool green retreat of Phantom Ranch is surrounded by cottonwoods and many grass and shrub species. Cottonwoods have extensive root systems and require a great deal of water to thrive.

But not all the plants that grow here are native to this place. Tamarisk (also known as saltcedar) is native to Eurasia. It was introduced in the early 1800s and is spreading rapidly along the streams of the arid Southwest. Tamarisk (also known as salt cedar) is a common invasive riparian weed species that is native to central Asia and the Mediterranean region. It was introduced to the United States in the early 1800s and is spreading rapidly along the streams of the arid Southwest.

Phantom Ranch is also a cultivated oasis. A careful look around the trees and plants of Phantom Ranch reveals an old peach orchard, pomegranate, fig, and olive trees and a lone date palm. These trees and shrubs tell of people who left their marks in this area not in wood or stone, but in the flora of the canyon’s floor.

Darting among the rocks and along the trail are many lizards and a few snake species as well. They are well adapted to the hot temperatures in the Inner Canyon. Many species avoid the heat by burrowing into the ground or taking shelter under a rock or in shade from a nearby tree. As cold-blooded creatures, reptiles such as lizards and rattlesnakes move between the sun and shady rock overhangs to control their body temperatures.

If you’re visiting Phantom Ranch, you may want to stop by the National Park Service Ranger station (built in 1966) located along the trail between the Phantom Ranch cabins and Bright Angel Campground, on the east side of Bright Angel Creek. Rangers there can give you the latest weather updates (also posted at the campground entrance and in the cantina at the ranch), answer your questions about that flower you saw on the trail, or make hiking suggestions for your day’s activity.

Listen to periodically updated Grand Canyon Ranger podcasts to get a sense of Phantom Ranch

Before Mary Colter and the Santa Fe Railroad, this area was known as a small outpost and tent camp called Rust’s Camp. The Inner Canyon was not easily accessible to most visitors until the early 1920s. At that time, a wooden suspension bridge replaced the small and adventurous cableway installed by David Rust in 1907 (Thybony 2001). The suspension bridge made cross canyon travel and crossing the Colorado River easier – especially for mule trains carrying tourists and provisions for inner canyon denizens.

David Rust operated a tourist camp here from 1903 onward that hosted early prospectors and a few sturdy and adventurous tourists. Rust was an early Grand Canyon settler who also improved the trails and transportation systems in parts of the Grand Canyon.

In addition to the cableway, Rust improved the trail down to Bright Angel Canyon from the North Rim. The additions and changes in amenities from Rust’s Camp helped open the Inner Canyon to tourism.

Hunting parties and canyon visitors stayed overnight at Rust’s camp. Rust made a number of changes to the landscape at this site. He planted cottonwood trees and fruit trees, irrigated the creek, set up and maintained tents for visiting tourists, and built a ramada for shade (near the current commercial mule corral).

The marks of Rust’s work may still be seen in the proliferation of shade trees around the commercial mule corral. With these accommodations, tourists could visit and stay comfortably in the canyon overnight – thus increasing inner canyon visitation. Perhaps the most famous visitor to the camp was President Theodore Roosevelt. While on a hunting trip to the North Rim after leaving the presidency, Roosevelt visited the camp in 1913 and used Rust’s cableway to cross the Colorado River (Anderson, M. 2001; Thybony 2001). After Roosevelt’s visit, Rust’s camp was renamed “Roosevelt’s Camp”.

The fruit and shade trees planted by Rust changed this inner canyon environment. Later canyon residents continued to water and maintain this cultivated oasis. Early Phantom Ranch meals were supplemented by fruits and vegetables from these gardens. Today, some of Rust’s trees still stand.

Photo: Yolonda Youngs

Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, under the auspices of the Santa Fe Railroad, designed an impressive body of architectural work – eight of the historic structures found at the South Rim and the only Inner Canyon developed area – Phantom Ranch. She worked at a time when few women held architectural degrees. She earned a level of notoriety and created an impressive array of buildings as the premier architect for the Santa Fe Railroad and the Fred Harvey company (Leavengood 1999).

She worked for the Fred Harvey Company from 1902 for almost 46 years. Colter attained her architecture degree at the California School of Design and started working for the Fred Harvey Company as an interior designer but soon worked her way up to designing structures. She was a dedicated architect – she was known to spend many hours at her sites overseeing construction.

Colter developed her own style of architecture that blended “indigenous” American Indian building designs and motifs as well as rustic building materials from locally available timber and rocks. Her resume at the Grand Canyon includes Hopi House (1905); interior of El Tovar (1905); the Lookout Studio (1914); Hermits Rest (1914); Phantom Ranch (1922); the Watchtower (1932); Bright Angel Lodge (1935); Fred Harvey Men’s Dormitory (1936); Dormitory for Harvey Girls also known as Colter Hall (1937) (Leavengood 1999, 42-44; Gratton 1992, 125). The original buildings designed by Colter and built for the area near Rust’s Camp (renamed Phantom Ranch by Mary Colter) included four native stone cabins and the north half of the dining lodge.

Colter’s Phantom Ranch cost $20,000 to build (paid for by the Santa Fe Railroad). The Civilian Conservation Corps built the rest of the Phantom Ranch buildings in the mid 1930s. The guest cabins are set at irregular widths, inspired by Craftsman Bungalow style of architecture that showcases stone and wood for their primary building elements. All materials (except the stones) used in the construction of the cabin complex were hauled down the canyon by mule. The site became a popular overnight stay for mule riding tourists and soon expanded to include additional tents and cabins, a recreation hall, bathhouse, dining area and a swimming pool. Socialites and celebrities of the 1920s found Phantom Ranch to be a fashionable destination and getaway. During these early years, the ranch grew much of its food on-site, with an orchard and garden, chickens and rabbits (for Sunday dinner) (Leavengood 1999, 42-44; Gratton 1992, 125).

A visit to Phantom Ranch offers a chance to step back in time, relax under the shade trees, and listen to the gurgle of Bright Angel Creek about a half mile up from where it flows into the Colorado River. Reservations at the ranch fill up months in advance. Today’s Phantom Ranch includes eleven guest cabins, four hiker dormitories, an employee bunkhouse and enough room for 92 overnight guests.

Although times and technologies have changed, the Phantom Ranch complex remains an isolated community dependent on limited access in or out of the canyon by foot, mule, or river boat. Mules in pack strings carry a majority of the daily supplies in and out of the canyon each day. Supplies for the Phantom Ranch operations include everything from two and a half tons of food for the cabin guests made at the cantina, to mail delivered to cabin workers and river runners, and even the garbage. The ranch employees run a composting system as well which can process up to eighty pounds of garbage a day (Thybony 2001, 27).

This small community is often in flux as cabin guests, concessionaire employees who manage and run the daily workings of the ranch, NPS rangers, backcountry patrol officers, mule wranglers and occasional river runners pass through or stay the night. These people may come to the ranch for a day or a few hours, they may be here to work or to visit and enjoy the scenery, but they all leave an imprint on this place and take away lasting impressions of their experiences. Those visitors who stay at the Bright Angel Campground must observe good backcountry ethics by packing in and packing out all the trash that they create or bring along.

Water is another carefully watched resource in the canyon. Every day in the summer, people at the ranch use 7,000 gallons of water and the Bright Angel Campground uses an additional 3,000 gallons (Thybony 2001, 27). Roaring Springs, at the head of Bright Angel Canyon, is the source for this water as well as the 500,000 gallons that are piped out of the springs and along the transcanyon pipeline to the South Rim’s Grand Canyon Village.

When visitors make the journey into the Inner Canyon to visit Phantom Ranch—perhaps by riding a mule all day, floating on the river for days or a week or negotiating the many switchbacks in the trails to hike down into the canyon—they enter someplace special. Phantom Ranch is a unique space in the Grand Canyon, one that you may visit only once in your lifetime yet it will make a lasting impression on you. No matter how you make the journey to this part of the canyon—even if only virtually through your computer—remember to take pictures, leave only footprints, and appreciate the resources and beauty of this inner canyon respite.

Written By Yolonda Youngs

References:

- Anderson, M. 2001. Along the rim: A guide to Grand Canyon’s south rim from Hermit’s Rest to Desert View. Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Association.

- Anderson, M. 1998. Living at the edge: Explorers, exploiters and settlers of the Grand Canyon region. Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Association.

- Gratton, V. 1992. Mary Colter: Builder Upon the Red Earth. Grand Canyon Association, Grand Canyon, Arizona.

- Loder, C. 2000. An Introduction to Grand Canyon Prehistory. Grand Canyon Association, Grand Canyon, Arizona.

- McNamee, G. 1997. Grand Canyon Place Names. Johnson Books, Boulder, Colorado.

- National Park Service. Phantom Ranch Walking Tour. (brochure). Grand Canyon National Park and Grand Canyon Association. Grand Canyon, Arizona.

- National Park Service. Plants of the Grand Canyon. Available at: http://www.nps.gov/grca/naturescience/plants.htm

- Powell, J. 1895. (Reprinted 1961) The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons. New York: Dover Publications, 259

- Schwartz, D. On the Edge of Splendor: Exploring the Grand Canyon’s Human Past. The School of American Research, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

- Thybony, S. 2001. Phantom Ranch, Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association. Grand Canyon Arizona.

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Library. “Plants”. Available at: http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/plants/saltcedar.shtml