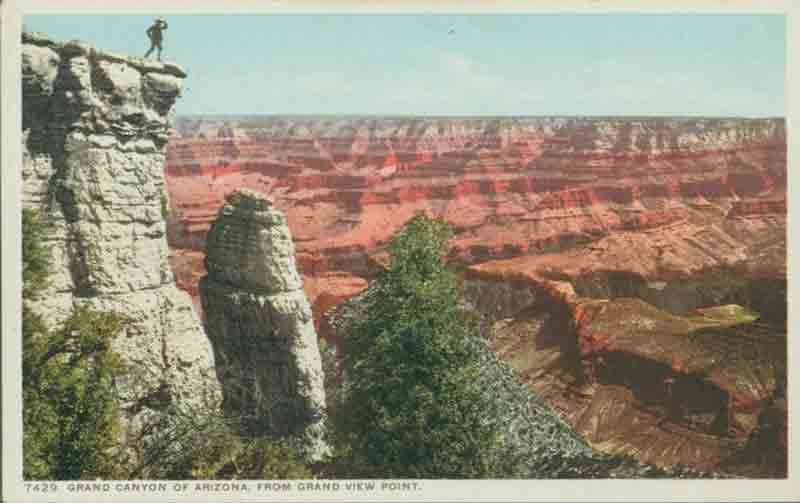

In the 1890s, mining activity developed in the area around Grandview Point, launched by a group of local miners that included Ralph Cameron and Pete Berry. The two men found just the right “color” in rocks on Horseshoe Mesa below the rim, filed claims in 1890 and profitably extracted copper, gold, and silver for over a decade before selling out. To get to their “Last Chance mine,” Berry and Cameron improved a trail down from Grandview Point in 1893, partially following an old Native American route, and used mules and ropes to haul up the ore. A realigned version of Grandview Trail takes hikers to Horseshoe Mesa and on to the Colorado River.

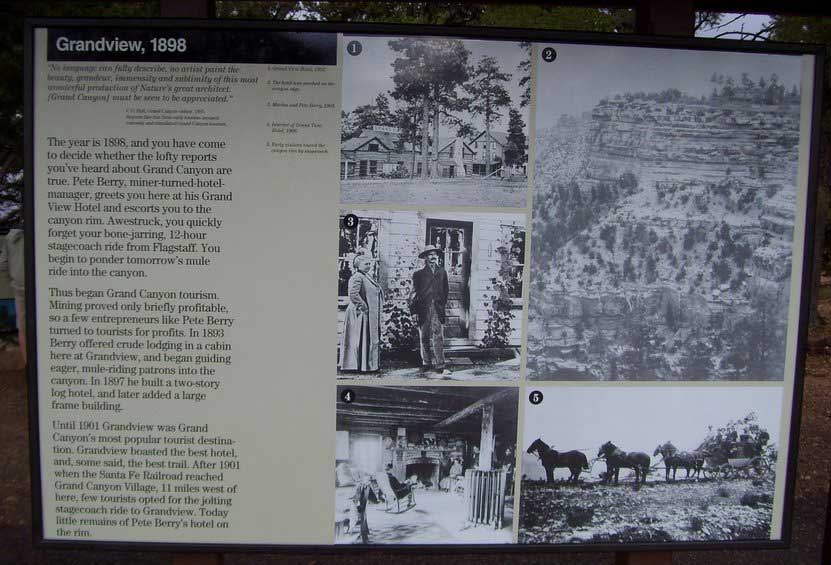

Nature tourism was also developing in the 1890s, and both Berry and Cameron diversified their incomes by launching visitor services. Berry put his efforts into Grandview Point where he and his wife Martha used the profits from their mine to build the rambling rustic Grandview Hotel between 1892 and 1897. Cameron invested his tourism energies farther west on the rim, constructing Cameron’s Hotel and Camps near the head of Bright Angel Trail at the Grand Canyon Village. Somewhat wistfully, Pete and Martha Berry boasted theirs was “the only first class hotel at the Grand Canyon” (Anderson 1998: 70). Their two-story ponderosa pine lodge featured Indian arts and crafts, a mark of Southwest authenticity that influenced visitors’ sense of place.

Hoping to cash in on the growing tourist trade, the Santa Fe Railroad built a rail line up from Williams, AZ, terminating at a depot in the heart of what became known as the Grand Canyon Village. When the Santa Fe line arrived in 1901, Pete Berry offered free stage transportation to the Grandview Hotel from the railway depot, equivalent to today’s free hotel shuttle from the airport.

Expecting a brighter future in tourism (and less physical risk), the Berrys sold their rights in the mining operation to a Chicago investor in 1902 who formed the Canyon Copper Company. The new company property included the Grandview Hotel, so the Berrys moved to their nearby homestead and built the three-story Summit Hotel. Unfortunately for the Canyon Copper Company, copper prices declined and the mines closed in 1907. By then, tourism had taken over as the main economic engine at the Grand Canyon. In 1905, the Santa Fe built the extravagant El Tovar Hotel on the rim a stone’s throw from its train depot, managed by the railroad’s tourism business partner the Fred Harvey Company. This entry into the tourism business by one of the wealthiest corporations in America drew customers away from the more rustic locally-owned facilities. Pete and Martha Berry’s hotel business suffered as a result, but they did not give up without a fight.

With hotel revenue declining, the Berrys subdivided their property and put up lots for sale hoping to create another town to compete with the Grand Canyon Village. But this venture failed.

Pete and Martha Berry conveyed travelers to their hotel at Grandview Point in wagons along a dusty, bumpy road. In 1925, the National Park Service began clearing a new road to Grandview as part of the East Rim Drive that today runs between Grand Canyon Village and Desert View Watchtower.

Photo: NAU.PH.90.9.1829. Jack Greening Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

The Santa Fe Railroad offered to buy the property, but the Berrys refused to sell out to their nemesis and instead sold their homestead and hotel to the California newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst in 1913. Hearst also bought all 200 acres of the Canyon Copper Company properties including the Grandview Hotel. The Berrys became caretakers of the Hearst property until 1919, delighted that a rich and powerful business mogul had snatched opportunity from the railroad company that drove them out of business.

Hearst never posed any threat to the Santa Fe Railroad, though. He kept the property primarily as a family retreat, having no need to profit from it. As soon as he purchased the property, he closed the two hotels. But for years afterward continued to dream of developing a tourist resort on the property. This troubled the National Park Service, which took over management of the Grand Canyon in 1919. Park managers worried about controlling haphazard tourist development so early park policy sought to concentrate private tourist facilities in the hands of a single concessionaire that would operate under a strictly regulated franchise. The Fred Harvey Company had evolved into that monopoly concessionaire and Hearst was a fly in the ointment.

With the hotels and other property structures deteriorating steadily after the Berrys retired and departed in 1919, Hearst finally dismantled the decrepit Grandview Hotel in 1928-29, selling some of its log beams for use in Mary Colter’s Desert View Watchtower then being built on the rim to the east. In 1941, the Park Service acquired the Hearst property through condemnation proceedings, against the vigorous opposition of Hearst lawyers. As one of America’s most prominent newspapermen (and the subject of Orson Wells’ classic film Citizen Kane), Hearst easily managed to garner journalistic support for his cause. One local paper called it a “Park Service Land Grab,” while county supervisors called it “Nazism” and “Russian tactics of the lowest denominator.” Nonetheless, the Park Service won the lawsuit. In 1959, it removed the remaining buildings, including the Summit Hotel. Mining structures on Horseshoe Mesa remain as historic artifacts of that era. Martha Berry died in 1931, Pete followed her in 1932, and both are buried at the Grand Canyon cemetery.

Today, other than a parking lot, trailhead, and sign commemorating the former hotel, Grandview Point reveals no visual clues of its colorful past. The Park Service has restored the site to look as “natural” as the forest that surrounds Grandview Point. (Anderson 1998: 67-75.)

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Billingsley, George H., Earle E. Spamer, and Dove Menkes. Quest for the Pillar of Gold: The Mines and Miners of the Grand Canyon. GCA, 1997.