Flanked on the east by the Navajo Indian Reservation and on the west by House Rock Valley and the Kaibab Plateau, Marble Canyon runs southwest for over sixty miles from Lees Ferry to the head of the Grand Canyon. Its name is actually a misnomer; there is no marble in this place. Powell, a self-taught geologist, knew this when he christened it. The canyon’s beautiful polished limestone struck him, and he thought it deserved this title. A little off the beaten path, the experience of Marble Canyon is best at river level. Here travelers witness the canyon’s beauty and its history.

Although breathtakingly beautiful, people have not always cherished and protected Marble Canyon as they do today. On January 21, 1963, not coincidentally the same day the Bureau of Reclamation closed the western diversion tunnel of the newly completed Glen Canyon Dam to begin filling Lake Powell, Floyd Dominy, the Bureau’s Commissioner, announced a plan to dam the Grand Canyon. As part of his Pacific Southwest Water Plan, Dominy included a dam in Marble Canyon. When the announcement came, the public put up little opposition.

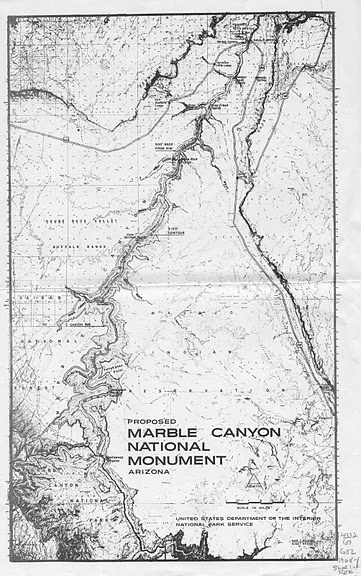

Why should they oppose this dam? Most people in 1963 were uninformed or even unaware of Marble Canyon; it did not have any protective designation and the National Park Service had no plans at that time to incorporate it into Grand Canyon National Park. Dominy’s proposed dam at river mile 39.4 (below Lees Ferry) was just another step in a planned staircase of dams for the Colorado River. The Bureau of Reclamation selected a site for the dam and drilled several tunnels in the limestone cliffs to investigate the character of the rock.

Some people did know about this place, however, and they fought vehemently to stop this dam. The Sierra Club, still tasting its loss over Glen Canyon, opposed it with extraordinary vigor. Martin Litton, a river runner and influential member of the club, helped spearhead a nationwide anti-dam lobby, which successfully blocked Dominy’s proposal. As a result, the Sierra Club lost its tax-exempt status, but gained supporters.

Many citizens, outraged by the government’s retaliatory revocation of the Sierra Club’s non-profit status, joined the Sierra Club to show support for its mission. Meanwhile, Arizona Senator Carl Hayden had failed for years to get the federal government to pay for a canal to bring Colorado River water to the cities and farms of central Arizona. The Pacific Southwest Water Plan included the canal he sought for two decades, but Hayden’s plans faced opposition from the California congressional delegation.

California wanted assurances that its water rights claims to the Colorado River would have priority over Arizona’s. The California delegation also objected to the Marble Canyon Dam due to effective lobbying by the Sierra Club, which had its headquarters in San Francisco. Hayden, who would leave office in 1968, knew that the only way to gain the needed support for the Central Arizona Project Canal was to accede to the demands of the California Congressmen and concede the dam at Marble Canyon.

Just as Floyd Dominy’s dream to fill Marble Canyon with a hydropower reservoir had failed, so did the dream of another early canyon explorer: Robert Brewster Stanton, a young entrepreneur who wanted to build a railroad through the Grand Canyon. As head of the Denver, Colorado Canyon and Pacific Railroad, Stanton knew one thing: Colorado had coal that California needed, and the best way to deliver this coal, he thought, was by rail through the Grand Canyon.

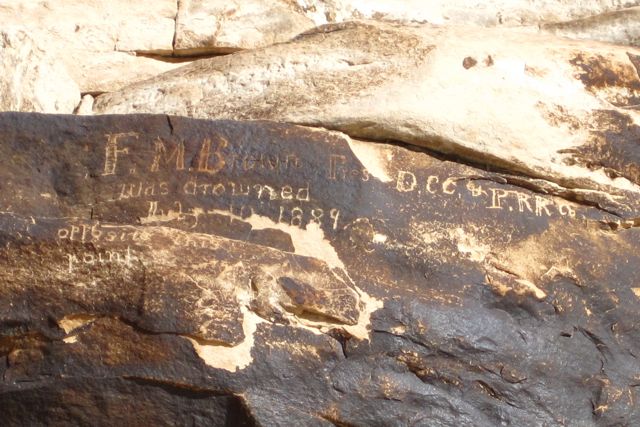

In 1889 with his investor and company president, Frank Brown, and a rag tag group of men, Stanton set out on a river trip to survey a rail route through the Grand Canyon. Destined for failure from the start, the expedition showed its inexperience.

By mile twelve Frank Brown had drowned, and in Twenty-Five Mile Rapid two more men, Peter Hansbrough and Henry Richards, also drowned. Forced to hike out of a side canyon called South Canyon at river mile twenty-nine, Stanton returned the next year to complete his expedition.

Although Stanton remained adamant about the possibility of a railroad through the Grand Canyon, he never found the support needed for his project.

Marble Canyon is truly a national gem. Among its many interesting archaeological treasures are 4,000 year old split-twig animal figurines of early desert cultures, as well as the storage granaries at Nankoweap Canyon.

The canyon holds the 12,000 year old remains of the now extinct Harrington Mountain Goat. It is home to the Pale Townsend’s Big-Eared Bat, and the highly endangered Kanab Ambersnail.

The foot of the canyon is home to one of the last populations of the endangered Humpback Chub, and the Paria River at the head of the canyon provides much needed silt and sediment for their survival.

The sheer rock cliffs of Marble Canyon make it virtually inaccessible to the outside world, but its inaccessibility has protected these natural treasures. On January 3, 1975, President Ford signed the Grand Canyon Enlargement Act, abolishing the national monument and incorporating Marble Canyon into Grand Canyon National Park. The law doubled the park’s size to 1.2 million acres.

Written By Mark Buchanan

References:

- An act to further protect the outstanding scenic, natural, and scientific values of the Grand Canyon by enlarging the Grand Canyon National Park in the state of Arizona, and for other purposes. Public Law 93-620. The Library of Congress, 1975.

- Martin, T. and Whitis, D. Guide to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon: Lees Ferry to South Cove. Fourth Edition. Flagstaff, Arizona: Vishnu Temple Press, 2008.

- Murphy, Shane, Gaylord Staveley. Ammo Can Interp: Talking Points For a Grand Canyon River Trip. Flagstaff, Arizona: Canyoneers, Inc., 2007.

- Pearson, Byron Eugene. Still the Wild River Runs: Congress, the Sierra Club, and the Fight to Save Grand Canyon. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2002.

- Powell, John Wesley. The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyon. New York: Dover Publications, 1961.