The entire network of trails within Hermit Basin (aka Waldron Basin) is due to Louis D. Boucher, an immigrant from Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada who arrived at the canyon’s South Rim before 1891, when other pioneers of the South Rim were just starting to stake out their personal spheres of influence. Boucher chose the area about eight miles west of what later became Grand Canyon Village, probably for the terrain, which allows multiple opportunities to descend through the typically steep Kaibab and Coconino cliffs. He probably helped Dan Hogan and others build the nearby Waldron Trail about 1896, and another early trail from Hermit’s Rest down past Sweetheart Spring to Hermit Basin about the same time. Unlike other canyon pioneers, he did not immediately record his trails as toll roads, but did record his “Silver Bell Trail” (the historic Dripping Springs and Boucher alignments combined) in February 1902, only a few months after the Grand Canyon Railway arrived at the rim to the east.

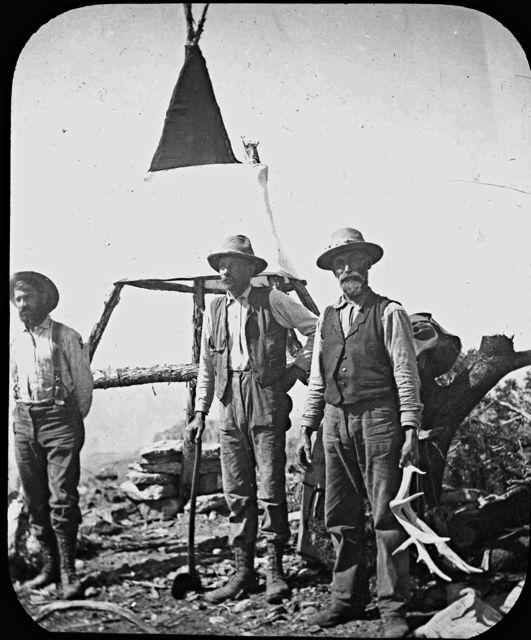

Boucher is an enigmatic historical character, known after 1910 as “the hermit.” There is little doubt that he was eccentric, riding about the area on his pure white mule, Calamity Jane, and seemingly preferring his own company to others—odd behavior for an early tourist guide. The Santa Fe Land Development Company apparently labeled him The Hermit after they bought out his interests to build their own Hermit Trail in 1909, no doubt to add a little romance to their advertisements, but he was not a true loner.

Boucher often worked for other pioneers along the South Rim, helping to manage Ralph Cameron’s camp at Indian Garden along the Bright Angel Trail and serving as a trail guide for others to make ends meet.

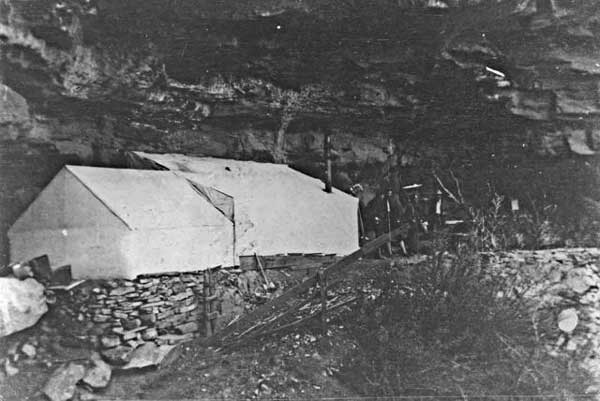

He also guided his own clients along the Silver Bell Trail and entertained them at a small camp at Dripping Springs and his larger camp nearer the river. He may have prospected for minerals as others did in those days, but the single mineshaft near his lower camp is the only evidence that he engaged in mining, and since the tailings of that mine appear devoid of valuable mineral, he probably maintained it solely to keep his legal claim to the nearby camp.

Another oddity surrounding Boucher is that despite his publicized proclivity for being a hermit, he has more canyon features named for him than nearly all other pioneers combined: Boucher Creek, Canyon, Trail, and Rapids; Hermit Rest, Road, Trail, Camp, Fault, Basin, Creek, Rapids, and Shale; and Eremita (Spanish for Hermit) Mesa and Tank. A hermit in life, perhaps, but in the afterlife he is as well remembered as a rock star!

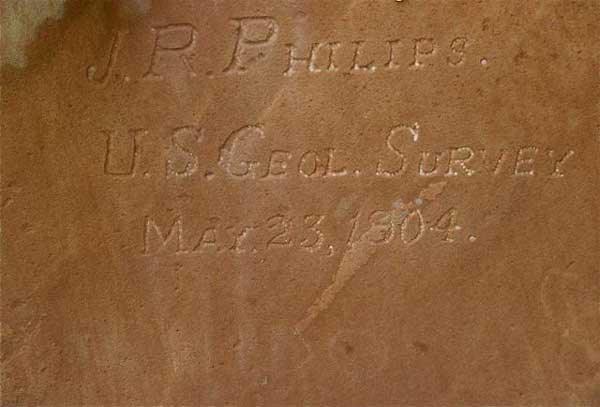

There is an inscription along the oldest alignment of the Hermit Trail by Harry Kislingbury with the date, 1889, nothing more. Kirby Collins, a hiker with the Grand Canyon Field Institute, decided to look into this man on the Internet and learned that Kislingbury was the son of Lieutenant Frederick Kislingbury. The elder Kislingbury had been a member of the disastrous Greely Expedition to the Arctic in 1881-84, whose starving survivors ate Kislingbury and other expedition members who died on the treacherous journey home!

An orphan, about 19 years old, Harry and at least one sibling, Walter, made their way to Flagstaff by 1886. Harry worked as a bank clerk, and for Pete Berry, and was also captain of the Flagstaff Company of the Arizona National Guard, commanded by another canyon denizen, Buckey O’Neill.

He was otherwise identified as a leading citizen in Yavapai and Coconino Counties, and upon his death in 1943, was buried in the pioneer cemetery in Prescott, Arizona. Dozens of simple inscriptions like Kislingbury’s dot the inner-canyon landscape. Such stories await the casual researcher.

Anyone who looks at a map can figure out dozens of backpacking opportunities in which the Dripping Springs and Boucher Trails play a part. The historic Dripping Springs Trail once began on the rim at Eremita Mesa and descended a shallow drainage through the Kaibab and Toroweap Formations before switchbacking down slickrock to the seeps at the base of the Coconino Sandstone. It is still there, a deteriorating, short, and steep trail that is rarely hiked because the National Park Service closed the trailhead access road in the 1990s. Little is left of it through the Coconino except for a few iron bolts and chiseled steps.

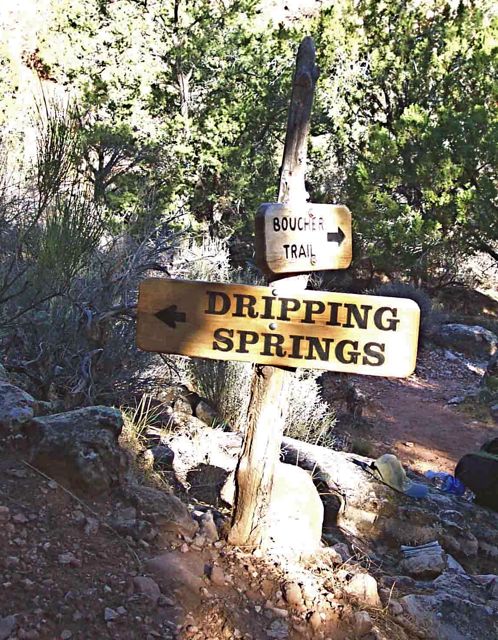

Hikers today walk down the Hermit Trail as far as the signed turnoff in the Esplanade Formation, then follow the Boucher Trail about ½ mile to a signed spur trail leading to the alcove where one principal seep in a series of seeps drips into a small pool. This modern alignment makes for a perfect day hike from Hermit’s Rest, perhaps six miles round trip with an elevation change of less than 1,500 feet, water for the hike back to Hermit’s Rest, and a shady alcove to wait out the heat.

The historic Dripping Springs Trailhead was also the beginning of the Boucher Trail, but today’s backpackers on the Boucher also start down the Hermit Trail, take the left turn on the Esplanade, and a right turn away from the spur to Dripping Springs. This is a narrow trail, little more than a path, as it continues several miles atop the Esplanade below Eremita Mesa and Yuma Point before dropping through the rest of the Supai Group.

Because the park’s trail crew does not maintain the Boucher, it is often sketchy in this section, and again through the Redwall as it crosses Travertine Canyon below Cocopa Point and makes its way down to the Tonto Platform. Here backpackers can turn left along the Tonto Trail toward the South Bass Trail far to the west, or turn right to intersect the many routes and trails to the east that lead back up to the South Rim.

The Boucher Trail continues down toward the Colorado River through Boucher and Topaz Canyons, and passes the ruins of Louis Boucher’s stone cabin, orchard, and mine about a mile short of the river.

A popular loop hike begins and ends with the Hermit Trailhead where you can take the Boucher (with a short detour to Dripping Springs for water) to the Tonto Platform, the Tonto Trail east, then Hermit Trail back up to Hermit’s Rest. From the Tonto Trail, it is only about a mile down to Boucher and Hermit Rapids where you can get more water and (in season) sit on a boulder and watch some rafters get drenched.

The Tonto trail crosses perennial Hermit Creek at the Park Service campground, where you should fill your water bottles before starting up the Hermit Trail. Additional water is available at Santa Maria Springs, about 2-4 hours from the rim. All water sources along this backpack should be treated for Giardia. For longer backpack loops, use the Boucher or Hermit Trails to reach the Tonto, then travel east and emerge along Bright Angel, South Kaibab, Grandview, or New Hance Trails.

Written By Michael F. Anderson

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael F. Along the Rim: A Guide to Grand Canyon’s South Rim from Hermit’s Rest to Desert View. Grand Canyon Association, 2001.

- There are at least a dozen published Grand Canyon trail guides that include the Boucher-Dripping Springs Trails, many of which can be purchased through the Grand Canyon Association website. At the same site, you can also obtain more detailed guides to the Hermit, South Bass, Bright Angel, South Kaibab, and Grandview Trails.