In the first half of the 20th century, the Bureau of Reclamation engaged in a building spree of canals, dams, and power plants across the West, helping to spur development by providing water, electricity, and recreational opportunities across the region. Nearly every substantial river was surveyed and evaluated for its potential as a dam site, including the Colorado River and many of its tributaries, leading to the construction Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam at either end of the Grand Canyon as well as many others. However, by the 1950s and 1960s many were growing tired of these economically costly and environmentally destructive projects, putting an end to major construction projects by the Bureau.

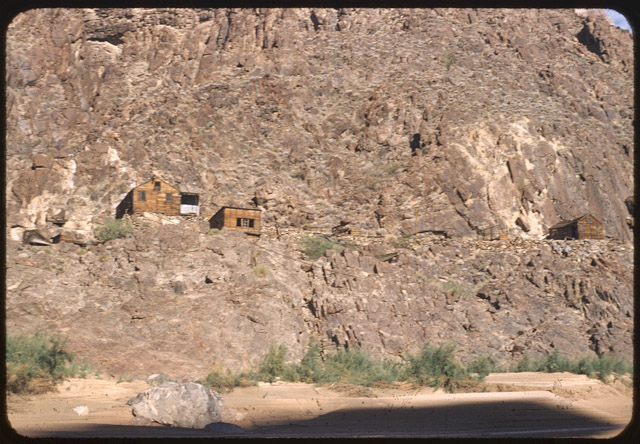

As early as the 1920s, the Bureau began putting forward proposals to build a dam and power plant at Bridge Canyon near Colorado River Mile 238. The canyon had received its name because a small natural bridge could be seen nearby along the river.

The dam site would have been 80 miles downstream of the national park’s western border at the time, but would have flooded lands on the Hualapai Reservation and Grand Canyon National Monument, creating a huge reservoir that would stretch all the way to Havasu Canyon. The proposed dam was sometimes referred to as Hualapai Dam in recognition of the Native Americans on whose reservation it would have been built.

In the 1920s and 1930s, neither the NPS nor environmental groups such as the Sierra Club paid much attention to the proposals, since the site was in a remote location and they believed it would not flood any “significant” areas of the Grand Canyon. Plans to build the dam languished until after WWII while other more pressing projects were constructed, though it was still considered an active proposal. In 1948 the NPS began to speak out in opposition to the dam, but was pressured by the Eisenhower administration in the 1950s to keep quiet on the subject.

The Hualapai mostly supported the dam, largely because of the revenue it would bring to their tribe. Proponents argued that the dam would help prevent silting at Lake Mead, would generate hydroelectric power for the region, and contribute money to the economy and the Hualapai people. Opponents argued that it would never make a sufficient return on its substantial costs, that it was superfluous with all of the other large dams in the area, and that it would cause unnecessary environmental and cultural damage.

The dam proposal languished again until the 1960s as California and Arizona fought over water rights to the Colorado River. In 1963, Arizona Congressmen proposed the construction of several dams and reservoirs, power plants, and other facilities as part of its Central Arizona Project that would bring Colorado River water to Arizona’s urban centers. This included a proposed 740-foot high dam at Bridge Canyon that would have been the tallest dam in the Western Hemisphere.

The NPS again spoke out against it, and the Sierra Club became actively involved in protesting it. Finally, in 1968 Congress approved the Central Arizona Project but purposefully omitted the Bridge Canyon Dam as well as another proposed dam at Marble Canyon just upstream of the national park. Occasionally some politicians, citizens, and businessmen still call for the government to build a dam at Bridge Canyon.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

Suggested Reading:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.

- Fradkin, Philip L. A River No More: The Colorado River and the West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981.

- Ghiglieri, Michael P. Canyon. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1992.