In some ways, development of the North Rim mirrored that of the South Rim, though a bit later in time and not on as grand a scale. The first concession did not open on the North Rim until 1917, almost three decades after the first businesses started on the South Rim. From 1917 to 1927, William Wallace Wylie and his daughter Elizabeth Wylie McKee operated the main accommodations on the North Rim at Bright Angel Point. However, the National Park Service practically forced her out of business when they gave the first permanent concession on the North Rim to the Union Pacific Railroad and its subsidiary Utah Parks Company. Similar to tourist development on the South Rim, the Railroad provided transportation to the Canyon, while the Parks Company established a hotel and range of services for its travelers. However, while the railroad arrived at the South Rim in 1901, no railroad line ever ran directly to the North Rim. Instead, the Union Pacific established a train station 100 miles away at Cedar City, Utah, and from there offered motor coach tours that allowed passengers to conveniently visit three National Parks: Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, and Zion.

The Utah Parks Company invested millions of dollars on the North Rim creating a tourist complex similar to but smaller than the South Rim’s Grand Canyon Village. A key difference was the fact that most tourist facilities on the South Rim predated Grand Canyon’s designation as a National Park. In the 1920s the National Park Service had control of the area and had to approve any construction plans. By this time, the NPS had developed a unique style of architecture that required builders to use natural materials and to make structures look like they had been solidly constructed with old-fashioned hand tools. Gilbert Stanley Underwood, the architect for the Grand Canyon Lodge, followed these NPS guidelines by using native stone and timber that matched the forested, rocky environment of the North Rim. Rather than a single large hotel, Underwood envisioned a centerpiece lodge surrounded by rustic cabins. The lodge’s exterior featured Kaibab limestone that seemed to rise out of the cliff at Bright Angel Point. In some places, he designed the stonework to resemble natural rock outcroppings. The upper verandah of the lodge faced south at the edge of the canyon, giving visitors a spectacular view. It included a glass-enclosed interior lounge as well as exterior terraces with an observation tower and massive outdoor fireplace.

The deluxe cottages and standard cabins that surrounded the lodge all blended with the local environment as well. Underwood let the hilly landscape and forest itself dictate where he placed the cabins and meandering paths instead of imposing a generic design. Furthermore, deluxe cottages included rustic elements such as half-log siding, stone corner piers and foundations, and limestone chimneys.

A crew of 125 men worked through the harsh winter of 1927-28 to finish the project, earning 50 to 85 cents an hour. Along with the lodge and cabins, the complex featured modern utilities, postal and telegraph services, baths and showers, as well as a barber shop, soda fountain, and curio store. To ensure the comfort of their guests, the Utah Parks Company built a state-of-the-art water and power system on the North Rim in 1927-29. The system still provides water and electricity at Bright Angel Point by pumping water nearly 4,000 vertical feet up to a 50,000 gallon water tank on the rim.

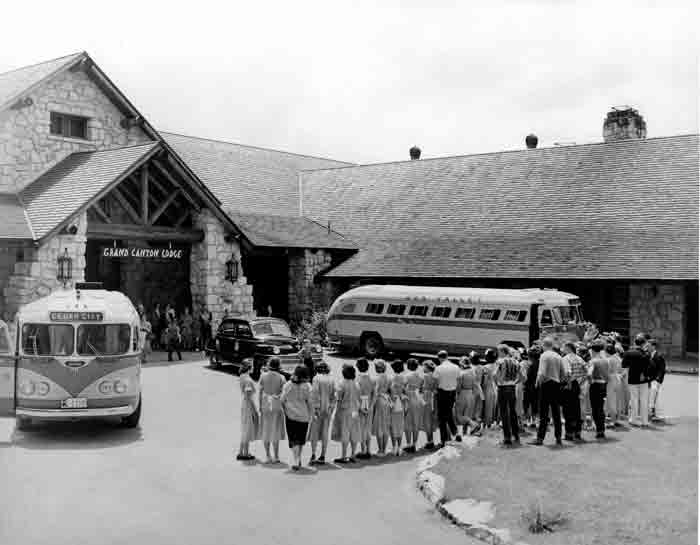

When the lodge opened in 1928, staff lined up at the door to welcome guests as they arrived in their motor coaches, and lined up again to sing a song as the visitors left. This “sing-away” quickly became a tradition at Grand Canyon Lodge. Every evening, the staff would put on a talent show followed by a dance. The lodge also allocated a small space for the National Park Service to display an exhibit [link to Interpreting the Canyon page] on the natural history of the Grand Canyon featuring examples of fossils, rocks, plants, and wildlife from the area.

On September 1, 1932, tragedy struck when a fire completely destroyed the four-year-old lodge. Fortunately, most of the surrounding cabins were spared, and visitors can still use them today. Even though the country was in the grips of the Great Depression, the Utah Parks Company vowed to rebuild. They constructed a temporary lodge on the ashes of the old in 1933. In the next two years, they built more cabins, a motor lodge beside the National Park Service campground, an employee dormitory, and a service station. The Company also extended water, sewer, and electrical lines to developed areas and supplied most utilities to the Park Service free of charge.

Rebuilding of the Grand Canyon Lodge itself began in 1936, and it opened in July of the next year. The new building used what was left of the original stone foundation, walls, and chimneys, but was more resistant to fire and had steeper roofs that could handle heavier snow loads. The architects insured that the lodge still blended in with its natural surroundings as much as possible, and even tried to enhance its rustic feel. The new structure featured Kaibab limestone masonry with cement mortar, Ponderosa log siding, and wooden shingles on the roofs, though it relied on more stone and less wood than the previous design. Inside, the interior space was more massive with high ceilings and exposed beams. It includes a recreation room, sun room, dining room, and “western saloon.” The Company chose not to include an observation tower or museum space in this new building.

The lodge closed for most of World War II, though they still rented out a few cabins for the sharply curtailed number of visitors. In the mid 1950s-60s, the National Park Service began its Mission 66 program, which led to many major construction projects throughout the National Park System. As part of this program, administrators envisioned radical changes for the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. They considered transforming Grand Canyon Lodge into an NPS visitor center with administrative offices, and creating two-story motel units to replace the cabins and campground area. These plans proved to be too costly and ambitious, and were never implemented. The National Park Service also tried to convince the Utah Parks Company to build more cabins, but they were not filling the ones they already had and were reluctant to invest in new ones.

Over the course of the 20th Century, as Americans became increasingly attached to the freedom that the personal automobile offered, passenger railroads around the country slid into decline. These changes had a significant impact on National Parks. While at the turn of the century most visitors were upper class transcontinental travelers who arrived at National Parks by train, as the decades wore on more middle and working class tourists started driving themselves to see their country’s natural wonders. At the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, the Union Pacific signaled the end of an era when it ceased passenger operations in 1971, three years after the Santa Fe Railroad did the same on the South Rim. In accordance with a stipulation in their concession contract, in 1972 the Utah Parks Company donated all their facilities to the National Park Service, which now leases the buildings to a concessionaire. The lodge has changed very little since 1937, and architectural historians consider it the most intact historic rustic lodge complex remaining in the National Parks. In 1987 it was deemed a National Historic Landmark, and is still considered to be in excellent condition.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Anderson, Michael, ed. A Gathering of Grand Canyon Historians. Proceedings of the Inaugural Grand Canyon History Symposium, January 2002. GCA, 2005.

- Harrison, Laura Soulliere. Architecture in the Parks: Excerpts from a National Landmark Theme Study. National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 1986.