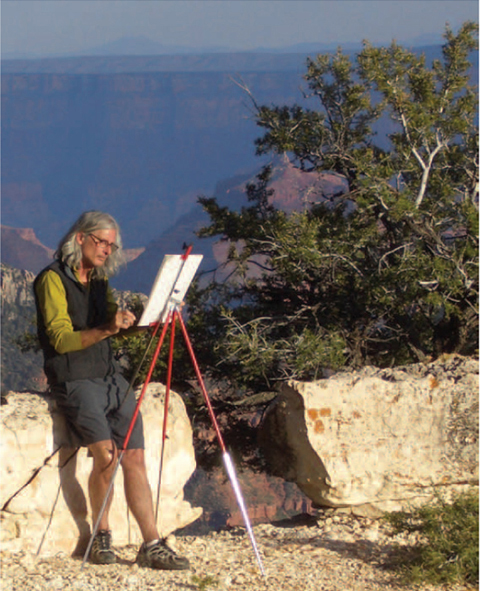

This Grand Canyon painting, “Above all Adversities,” is by contemporary artist Lorenzo Cassa. Used by artist’s permission.

Painting across time: Grand Canyon landscapes on canvas

While visiting the Grand Canyon in May 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt said of the landscape, “Do nothing to mar its grandeur, sublimity and loveliness. You cannot improve upon it.” Many of the millions of visitors since that time likely would agree that human artistic endeavors cannot improve upon the beauty of the Grand Canyon, yet that has not stopped scores of painters from trying to capture something of its sublime essence. Indeed, by the time Roosevelt visited the South Rim, the palette of Bright Angel Shale green, Coconino Sandstone red, and Kaibab Limestone white had already graced the canvases of scores of painters. Their works and those of artists throughout the 20th century have helped to shape our national identity, express our understanding of the importance of nature while eliciting support for the National Parks, and draw people westward to experience the beauty and culture firsthand.

The story of the American West often entails legends of men and women seeking their fortunes and personal fulfillment. In a way, those tales reflect the young United States’ attempts to forge an identity that would separate it from its European parents. The early sketchers and landscape painters of the Grand Canyon did more than spread appreciation for the chasm across the United States and world – they helped establish a sense of national identity that could hold its own against the high cultural accomplishments of Europe. If, as many Americans believed in the 19th Century, nature shaped culture and pioneering shaped national character, then America’s magnificent landscape implied a magnificent nation in the making. The early painters, along with writers of romantic literature and scientists accomplishing great geologic surveys, helped to shape our national narrative.

During the early 19th century, a young United States compared itself with Europe and, despite impassioned patriotism, often found itself wanting. As environmental historian Alfred Runte explains in National Parks: The American Experience, “the United States agonized in the shadow of European standards. Unlike the Old World, the new nation lacked an established past, particularly as expressed in art, architecture, and literature. In the Romantic tradition nationalists looked to scenery as one form of compensation. Yet even the landscapes of the United States, knowledge of which was then confined to those in the eastern half of the continent, were nothing extraordinary. Confronted with the obvious, Americans had little choice but to admit that the landmarks of Europe, especially the Alps, were no less magnificent.”1 That changed with the addition of western lands to the United States. Nowhere in the world was there anything quite like the Grand Canyon. To appreciate the works of 19th century painters such as Thomas Moran or contemporary painters such as Bruce Aiken, one must acknowledge the art of the scientist-explorers – their maps and sketches brought the first visual interpretation of Grand Canyon to people in the Eastern United States and around the world.

This map, titled “Rio Colorado of the West,” by F. W. von Egloffstein was one of the first visual representations of the Canyon. The map also illustrates routes of exploration taken by Ives’ expedition during 1857-58.

Photo: Courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

The first recorded Euro-American artists of the Grand Canyon did not reach the area of the South Rim now called Grand Canyon Village, where most visitors since the late 1800s have traveled. In 1857, Germans Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen (1825-1905) and F.W. von Egloffstein (1824-1898) accompanied Lieutenant Joseph Ives’ scientific expedition that approached Grand Canyon from the southwest. Egloffstein served as topographer and Möllhausen as “artist and collector in natural history” on the expedition, which traveled up the Colorado River via the steamship Explorer then continued on foot in what now is western Arizona.2

The purpose of the expedition was twofold: to determine the navigability of the Colorado River as an interior transportation route, and to survey and document scientific information about the river and the canyon through which it flowed.

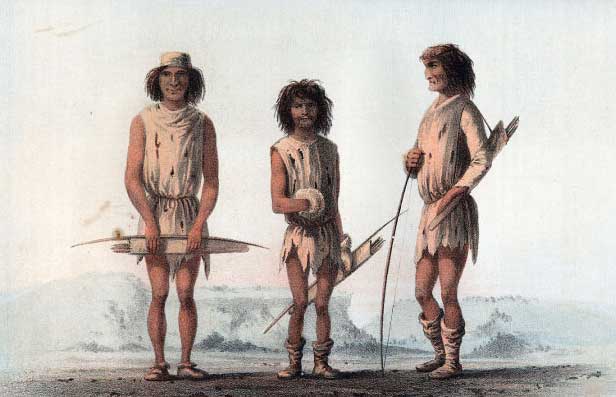

A perhaps unexpected bonus of the expedition, at least from our contemporary perspective, comes from Möllhausen’s and Egloffstein’s artistic representations of the Grand Canyon and the Native Americans they encountered. The sketches and engravings were published in 1861 as part of Ives’ official Report Upon the Colorado River of the West.

As Kevin C. McKinney of the U.S. Geological Survey wrote in a 2002 digital release of the report, “Möllhausen romantically captured the canyon’s awesome towering cliffs, mesas, and colorful native tribes.” 3

In addition to a map, Egloffstein also drew eight panoramic scenes that were published in the report. He accompanied several Western scientific expeditions and in 1865 he patented a photo-engraving technique that used a screen, an early version of what became half-tone printing.

Möllhausen’s pen-and-ink drawings and watercolors included “End of Navigation on the Colorado River – Seen from the Black Canyon,” “Gorge in the High Plateau and View of the Colorado Canyon,” as well as drawings of the Hualapai, Mohave, Apache, Chemehuevi, Navajo, and Hopi Indians, and prehistoric ruins on Pecos River in New Mexico. Most of Möllhausen’s original works were destroyed in Berlin during World War II, but many of his sketches live on as lithographs, either in the Ives report or in books published in Germany and the United States.4

After the Civil War ended, the federal government again turned its attention to exploring the American West. John Wesley Power took two trips by boat down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, one in 1869 and a second one sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution in 1871-1872. On his second expedition, Powell was accompanied by photographer John K. Hillers and young artist Frederick Dellenbaugh who provided a remarkable visual record of the little known and rarely seen canyons of the Colorado.5

The bulk of the credit for bringing public attention to the Grand Canyon through visual imagery usually goes to Thomas Moran. Moran visited the Yellowstone region in 1871 and afterward painted a giant masterpiece depicting the scenic grandeur of the place. This painting was purchased by the US Congress and is often credited for helping convince Congress to designate Yellowstone a National Park in 1872. Seeing the political power of Moran’s painting, Powell convinced Moran to join him and Jack Hillers on a trip to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon in the summer of 1873.

This was Moran’s first view of the Canyon. On this short visit, he sketched, painted, and worked with Hillers on photographs. When Moran returned home to New Jersey, he produced a number of sketches and paintings including another giant 7’ X 12’ canvas titled “The Chasm of the Colorado,” which Congress purchased for the extraordinary sum of $10,000. In 1875 when Powell wrote the account of his earlier expeditions down the Colorado River for Scribner’s Monthly, Moran’s illustrations–not Dellenbaugh’s–accompanied it, even though Moran had never been down the river.

Another important publication in 1882 brought much attention to the Grand Canyon both for its remarkable illustrations and for its soaring prose: Clarence Dutton’s Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, illustrated by both Thomas Moran and William Henry Holmes. In 1880 Powell arranged for Dutton to undertake a major scientific expedition to the Grand Canyon. Dutton was equally a scientist, philosopher, and poet, while Holmes similarly combined the skills of a geologist and scientific illustrator. Moran did not attend this expedition, but he prepared paintings for Dutton’s 1882 book based on his 1873 sketches, as well as sketches by Holmes and photographs by Jack Hillers. For more on Dutton’s publication and his reaction to the great abyss, visit our Nature, Culture and History page.

Emery Kolb (left) and Frederick Dellenbaugh (right) at the John Wesley Powell memorial at Powell Point on the South Rim, taken in 1921 at an event to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Powell’s second expedition down the Colorado River. The flag is from Powell’s boat, the Emma Dean, and the book sitting on the flag is a copy of Dellenbaugh’s A Canyon Voyage—the very same book that the Kolb Brothers used on their 1911-1912 river trip through the Grand Canyon.

Photo: National Park Service, Grand Canyon Museum Collection, GRCA-5533.

Emery Kolb (left) and Frederick Dellenbaugh (right) at the John Wesley Powell memorial at Powell Point on the South Rim, taken in 1921 at an event to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Powell’s second expedition down the Colorado River. The flag is from Powell’s boat, the Emma Dean, and the book sitting on the flag is a copy of Dellenbaugh’s A Canyon Voyage—the same one that the Kolb Brothers used on their 1911-1912 river trip. Emery presented it to Dellenbaugh as a gift.

Photo: National Park Service, Grand Canyon Museum Collection, GRCA-5533.

Moran’s paintings contributed substantially to the movement to create national parks in the West in the late 19th century. Biographer Fritiof Fryxell writes that Moran holds “a unique and honorable place” in the history of the National Parks because of his influence. “The American scene he made his own, and he brought back with him from the Far West a new motif for American artists. He painted the landscapes of a number of National Parks and Monuments, and, by means of his pictures, made them familiar to the public, in each case before they were made into federal sanctuaries.” 6 Robert Allerton Parker, in a 1927 article, called Moran a pioneer who “went forth in search of beauty as others were in search of copper, gold and oil. He was creative because he awakened the American consciousness to the permanent value of those wide, measureless expanses of wilderness, of sky and mountain and extravagances of Nature, as natural resources of beauty, to be prized and conserved and held as great national parks.” 7

Moran’s connection with Grand Canyon persisted for four decades, in part because of a railroad marketing campaign that brought many other painters to the chasm and drew the American populace westward.

On September 17, 1901, the first railroad passengers arrived at Grand Canyon. The event was photographed and memorialized as historic. The train ride from Williams offered comfort at a price of $3.95, compared with a $15 stagecoach ride that took eight hours from Flagstaff. But the railway line to the Canyon brought more than tourists – it became part of a marketing campaign, offering free passage to eastern artists who would stay and paint the chasm. Those landscape paintings brought the grandeur of the canyon to people who could not travel across the country to experience it first-hand.

William Simpson, general manager and executive of Santa Fe Railway’s promotional operations, commissioned dozens of artists who produced images for ads, brochures, menus and calendars as well as full-size paintings to sell. In addition to Thomas Moran, these painters included William R. Leigh (1866-1955), Louis Akin (1869-1913), Edward Potthast (1857-1927), and Oscar Berninghaus (1874-1952). Simpson’s marketing strategy helped bring the railway from the edge of bankruptcy to profits. As he told an interviewer, “I think that we were the first road in the land to take art seriously, as a valuable advertising adjunct. We have never skimped. We use the very best art that can be bought and we reproduce it in the very best way that it can be reproduced.” 8

The creations of those painters went beyond the calendars and souvenirs they graced and helped shape Americans’ views about the West during the late-19th to mid-20th century. During that era, many Euro-Americans regarded indigenous peoples through an ethnocentric worldview that reduced their varied and complex cultures into a singularly primitive part of the “natural” environment. T.L. McLuhan writes in Dream Tracks that railway advertising tapped that ethnocentricity: “With patriotic drama and allure, the railroad’s advertising became a sustained hymn to natural America. The imagination was encouraged to roam into the farthest reach of the wilderness, where an ideal new world was promised – the exotic and simple life of an earthly paradise.” The art of the early 20th century west “offered aesthetic and spiritual values not attainable in the urban metropolis, it promoted tourism as the new religion.” 9

Tourism flourished, and today the people who visit museums to see landscape art also can see those landscapes somewhat preserved because of the National Park Service. From Thomas Moran, who made a name for himself painting Yellowstone before Major John Wesley Powell asked him to paint the Grand Canyon, to the artists one might see today brandishing brushes on canvases along the South Rim, people from around the world have interpreted the Canyon through their eyes and hands. Those paintings hang in museums and private collections, connecting people who have never traveled to Arizona with a myriad of interpretations of its awe-inspiring beauty.

Written By Patricia Biggs

Further Reading:

- Anderson, Nancy K. Thomas Moran. National Gallery of Art, 1997.

- Dellenbaugh, Frederick Samuel. A Canyon Voyage: The Narrative of the Second Powell Expedition. (There are multiple editions of this book published between 1908 and 2012. The 1962 edition is especially recommended.)

- Dellenbaugh, Frederick Samuel. The Romance of the Colorado River.

- D’Emilio, Sandra, and Campbell, Suzan. Visions and Visionaries: The Art and Artists of the Santa Fe Railway. Gibbs Smith Publishers, 1991.

- Dutton, Clarence. Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District (1882).

- Fowler, Don D. Myself in the Water: The Western Photographs of John K. Hillers. Smithsonian Institution, 1990.

- Kinsey, Joni. The Majesty of the Grand Canyon: 150 Years in Art. Pomegranate Press, 2004.

- Wilkins, Thurman. Thomas Moran: Artist of the Mountains. University of Oklahoma Press, revised edition, 1998.

footnotes

1Alfred Runte, National Parks: The American Experience, second edition, revised. (Lincoln, Neb., and London: University of Nebraska, 1987) 7-8.

2Lieut. Joseph Ives, Report Upon the Colorado River of the West. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1861), 21. Digital copy published by U.S. Geological Survey Library, 2002.

3Kevin C. McKinney, introduction to 2002 digital edition of Report Upon the Colorado River of the West. U.S. Geological Survey.

4Robert Taft, “The Pictorial Record of the Old West: VI. Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen,” Kansas Historical Quarterly, August 1948. Online at http://www.kancoll.org/khq/1948/48_3_mollhaus.htm

5The Beinecke Library at Yale has Dellenbaugh’s papers, photographs, and correspondence, along with a short biography at: http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/digitallibrary/dellenbaugh.html

6Fritiof Fryxell, “The Man,” essay in Thomas Moran: Explorer in Search of Beauty. (East Hampton, N.Y.: East Hampton Free Library, 1958) 11.

7Robert Allerton Parker, “The Water-Colors of Thomas Moran,” essay in Thomas Moran: Explorer in Search of Beauty. (East Hampton, N.Y.: East Hampton Free Library, 1958) 78.

8T.C. McLuhan, Dream Tracks: The Railroad and the American Indian, 1890 – 1930, with photographs from the William E. Kopplin collection. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1985. Quote from page 18.

9Ibid, 16-18.