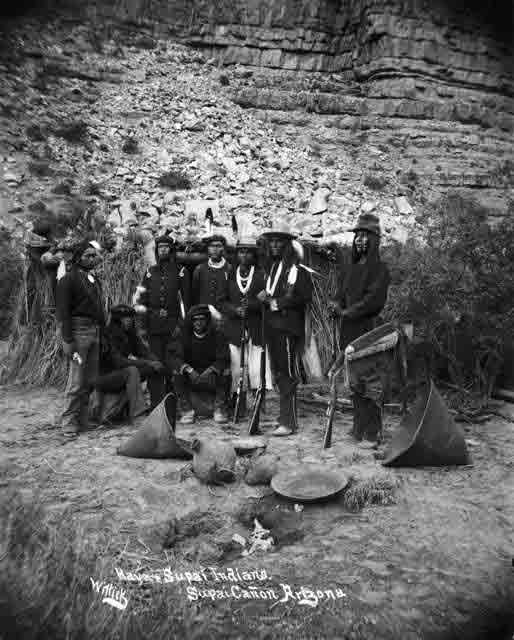

Today, most of the Havasupai people, or the Havasu ‘Baaja, live in Supai, a tributary canyon to Grand Canyon. But historically, they lived across a broader expanse, as far south as Bill Williams Mountain and east to the Little Colorado River. They moved up and down the vertical layers of the Grand Canyon, depending on seasons. During the fall and winter, they lived on the Colorado Plateau (the level of the Canyon’s rim), hunting and gathering food. In the spring and summer, Havasupai families farmed the Tonto Platform (including Indian Garden) and other arable areas, harvesting corn, beans, squash, melons and pumpkins. They did not encounter any European explorers until the Spanish priest Francisco Garcés traveled to Havasu Canyon in 1776. Garcés later traveled east to the Hopi mesas, and it is his report that tells of another Havasupai village as far east as Moencopi Wash, well beyond the Grand Canyon.

The Havasupai did not have to contend much with Euro-American intrusion until the late 1800s, when men looking for adventure or mineral riches traveled to the Canyon. These newcomers explored the landscape of the Grand Canyon by following trails of the Havasupai, Hopi, Cohoninas and Ancient Puebloans. The Euro-Americans, upon finding irrigation ditches and the remnants of cultivated fields on the Tonto Platform, named the area Indian Garden.

The Santa Fe Railroad opened a line to Grand Canyon in September of 1901. Two years later, President Theodore Roosevelt visited the canyon and rode down Bright Angel Trail. He met Yavñmi’ Gswedva (known as Big Jim to Anglos) and Billy Burro, two Havasupais who lived with their families at Indian Garden. Roosevelt told the Havasupai that a park was being created and they had to leave Indian Garden. Although Gswedva did as Roosevelt requested and moved his family out of Indian Garden to a cave higher up Bright Angel Trail, he continued to farm Indian Garden. Billy Burro and his wife, Tsoojva, remained at Indian Garden until the National Park Service forced them out in 1928.

For decades, the Havasupais were restricted to a 518-acre reservation in Havasu Canyon, part of their ancestral home. In 1975, Congress returned 185,000 acres of canyon and rim territory to the Havasupai Tribe. During the decades from the creation of the small Havasupai Reservation in 1882 and the enlargement in 1975, the Havasupai had to adjust the way they used their environment. More and more, they counted on farming, wage labor and tourism for survival.

Written By Patricia Biggs

References:

- Hirst, Stephen. I Am the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon Association for the Havasupai Tribe, 2006.