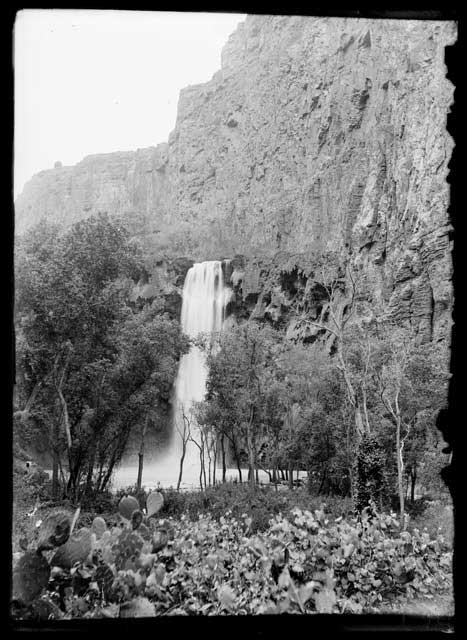

The breathtaking waterfalls and gorgeous blue-green water of Havasu Creek are just one of the features of Havasu Canyon that attracted Native peoples to this special location and that have drawn many thousands of visitors down the Hualapai Trail over the centuries in recent times. (Click photos to enlarge)

Photo: Paul Hirt

Near the western edge of the Grand Canyon a historic pathway, today known as the Hualapai Trail, winds its way down into what constitutes the present-day Havasupai Indian Reservation. For centuries, it has been an artery connecting Native Americans, Europeans, and Euro-Americans in a variety of ways at the canyon. From missionaries to miners, from traders to tourists, this trail has helped bring many people from many walks of life deeper into the heart of the Grand Canyon.

As with other trails at the canyon, it likely began as an animal trace that became worn into a path as early Native Americans hunted and gathered along it. The Havasupais developed this trail more specifically to give them a passageway between their homes on the rim and floor of the canyon, which in turn connected them to other village sites, to other Native American groups, and to locations for hunting animals or gathering plants or minerals. They used this trail, and many others that they developed around the Grand Canyon, to trade with neighbors such as the Hopis and Hualapais. They would drink from springs seeping out of the walls of the canyon as they traveled up and down these trails.

Father Francisco Garces, a Spanish missionary from near modern-day Tucson, was the first to leave a written record of Euro-American contact with the Havasupais in their canyon home. He traveled down what is now known as the Havasu Canyon Trail to visit the tribe in 1776, the same year that English colonists in the eastern edge of the continent were declaring their independence. The next recorded interaction between Havasupais and Euro-Americans involving this trail happened in 1857, when Lieutenant Joseph Ives of the U.S. Army and his expedition crashed their boats along the Colorado River. They traveled overland to Havasu Canyon and descended the trail there on their hands and knees because they were scared of what it might contain.

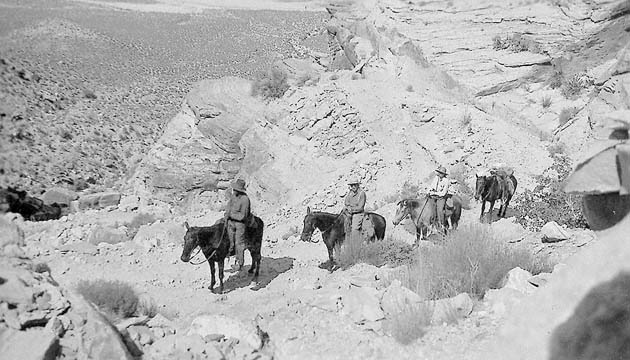

At the dawn of the 20th century, William Wallace Bass arrived in the area. He became a friend and advocate for the Havasupais after they helped him survive and settle nearby at Bass Camp. To supplement his mining activities Bass began conveying tourists into the Grand Canyon, sometimes to Supai Village via another trail called the Topocoba Trail. When he and his guests arrived at the bottom of Havasu Canyon, a delegation of Havasupais would come out to escort them to Supai Village. If guests happened to arrive at the right time, they would witness dances, ceremonies, or feasts. Bass also carried mail to the village along this trail.

Today the Havasupai Reservation is still mainly accessible by hiking or riding horses and mules down Hualapai Trail. There are no roads to accommodate automobiles or any other kind of vehicle, though occasionally helicopters swoop into the Supai Village. Tourists must start their trip into Havasu Canyon at Hualapai Hilltop, almost 200 miles west of Grand Canyon Village. Because the Havasupais are so conscious of the impact of visitors on their sacred homeland, they assess environmental care fees and entry fees to help cover the costs of keeping their canyon clean. Only a limited number of visitors are allowed in the canyon at a time, and all must get advance reservations and register at the tourist office in Supai village.

Havasu Canyon is on the western edge of the Grand Canyon’s Grand Scenic Divide. Therefore, visitors viewing the Grand Canyon from the hilltop may think it’s a different canyon than the one most people experience at the Village area within the national park. Here, rather than having numerous buttes dotting the inner canyon, it almost appears that there is a canyon within a canyon. Above are bold white cliffs of Coconino Sandstone, under which are slopes of soft shale, followed by the Esplanade, a broad plateau with little vegetation that forms the edge of the inner canyon.

The walls of the canyon still exhibit the classic layering of rocks seen elsewhere in the Grand Canyon, but are eroded differently. Many of the limestone layers feature fossils of sponges and other ancient sea life. Studying these types of fossils has helped scientists better understand the age of the earth and the evolution of living organisms. Furthermore, many ancient ruins and more modern Native American structures, as well as pictographs and petroglyphs, are still tucked away among crevices and under rock outcroppings. The Havasupai tribe has chosen not to reveal their location to outsiders because they consider them sacred and do not want them disturbed.

The eight-mile hike from Hualapai Hilltop, which sits almost one mile above sea level, to Supai 2,000 feet below is moderately difficult. The upper portions of the trail pass through a desert environment with plants such as yucca and agave. It begins by descending along steep switchbacks through the Coconino Sandstone. From here it follows a long talus slope of rocks that have eroded from the above layers to cover the Hermit Formation. Farther down the trail, Mount Sinyella can be seen in the distance. The Havasupais believed the mountain was inhabited by spirits that, if disturbed, would cause floods or strong winds that would carry people away as they hiked along the trail.

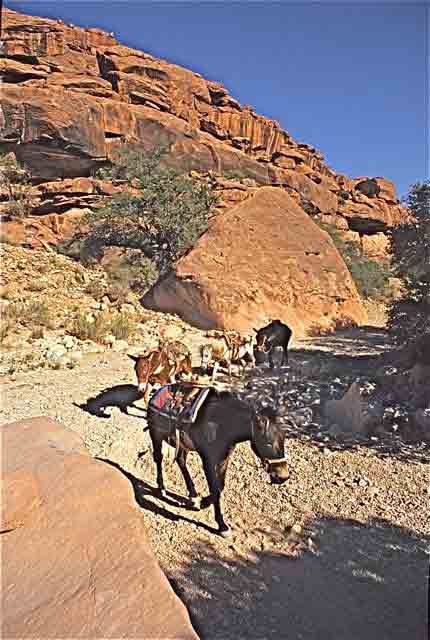

Once the trail reaches the floor of Hualapai Canyon, it follows a dry creek bed. As the canyon passes through the Esplanade it cuts deeper, and the open landscape gives way to a narrow defile and the color of the cliff walls turns into a darker, rusty red as the trail reaches farther into the canyon. After several more dry miles, Hualapai Canyon intersects with Havasu Canyon at Havasu Creek and everything suddenly changes. Here the desert landscape explodes into a burst of lush green vegetation where Havasu Creek winds through the canyon. Visitors can hear and smell the water before they can see it.

Havasu Creek is formed by a series of springs that emerge along the trail, eventually coming together to form a strong creek. The water is clear, containing minerals that form a limestone substance known as travertine. This coats the stream bed, and the refraction of light in the water makes it appear to be a rich turquoise-blue. Along Havasu Creek people can lounge under large cottonwood trees and admire redbud and ash trees. Fauna include lizards, mule deer, desert bighorn sheep, ringtail, and rock squirrel. Birds include the American dipper, swallow, and canyon wren.

After the junction of the two canyons, the trail follows Havasu Creek to Supai Village. Along the way hikers will see Havasupai farms with irrigation ditches that divert water into fields and pastures fenced with barbed wire. The village appears to be a green oasis surrounded by barren red rocks. In the wider portion of the canyon residents graze their horses or plant crops and fruit trees. Almost all of the needs of the canyon residents, such as groceries and clothing, are supplied by pack horses traveling up and down the Havasu Canyon Trail.

After the village, the trail takes hikers to a series of waterfalls along the creek. About 1.5 miles from the village the trail reaches the first major waterfalls, Navajo Falls, named after respected Havasupai leader Chief Navajo. The water pours over cliffs formed in the Redwall Limestone and built up with travertine deposits. After this the canyon continues to narrow and deepen. Campgrounds are located just beyond Havasu Falls, which used to be known as Bridal Veil Falls until a flood changed the river channel. Farther along the trail are Mooney Falls, named after a miner who fell to his death there in 1880. The trail down the rock cliff to Mooney Falls follows the path of an old miners’ route down steps carved in the travertine and through two tunnels that they blasted through the rock. The Havasupais treasure these sacred waterfalls and refer to the 195-foot tall Mooney Falls as the Mother of the Waters.

From Mooney Falls it is a seven-mile hike to the Colorado River. The trail continues on to Beaver Falls, the last major falls before the creek reaches the river. Along the route cottonwoods and ash line the water as it drops from pool to pool. The Havasupai Reservation ends at Beaver Falls, so the rest of the creek runs through Grand Canyon National Park. At the falls, Havasu Creek cuts into the Temple Butte Formation. Below this is the Tonto Group with exposed Muav Limestone. Occasionally, the trail leaves the creek, and takes on a desert feel with mesquite and cacti along the slopes. It ends at the Colorado River where the warm and bright blue-green waters of the creek merge with the cold, dark waters of the Colorado River.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke and Paul Hirt

References:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Babbitt, James, Scott Thybony and George Huey. Grand Canyon Trail Guide: South and North Bass. Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1996.

- Billingsley, George H., Earle E. Spamer, and Dove Menkes. Quest for the Pillar of Gold: The Mines and Miners of the Grand Canyon. GCA, 1997.

- Dobyns, Henry F. and Robert C. Euler. The Havasupai People. Phoenix: Indian Tribal Series, 1971.

- Havasu ‘Baaja: People of the Blue Green Water. DVD. Havasu ‘Baaja L.L.C., 2004.

- Hirst, Stephen. Havsuw ‘Baaja: People of the Blue Green Water. Supai: Havasupai Tribal Council, 1985.

- Iliff, Flora Gregg. People of the Blue Water: My Adventures Among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians. New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1954.

- Morehouse, Barbara J. A Place Called Grand Canyon: Contested Geographies. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996

- Shields, Kenneth Jr. The Grand Canyon: Native People and Early Visitors. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

- Thybony, Scott. Grand Canyon Trail Guide: Havasu. Grand Canyon Association, 1996.