Long before Congress designated Grand Canyon National Park in 1919, tourists began visiting the famous chasm. The earliest sightseers came via wagon or stagecoach, staying for days or weeks at a time in their own canvas tents or primitive commercial hotels, cabins, and tents. However, when the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway finished a spur line that allowed travelers to take a train almost directly to the rim of the Grand Canyon in 1901, these early tourism enterprises underwent a major transformation.

Most railroad passengers at this time were wealthy, and expected to travel in style and comfort. The train brought many more people than wagons and stagecoaches, creating a shortage of adequate accommodations at the rim. To provide the luxury that their well-heeled customers expected, the Santa Fe Railway in 1902 commissioned construction of El Tovar, a four-story hotel just a few dozen feet from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. When construction finished in 1905, El Tovar dwarfed nearby hotels and tents. With almost 100 rooms and a capacity for nearly 200 visitors, it doubled the number of guest rooms at the South Rim. As a first-class hotel, it helped the Santa Fe Railway draw more affluent visitors to the Grand Canyon. However, it also helped drive many pioneer entrepreneurs out of business because they could not compete with this big national corporation.

The hotel cost $250,000 to build, and many considered it the most elegant hotel west of the Mississippi River. Santa Fe Railway planners originally thought of naming the hotel “Bright Angel Tavern,” but instead they christened it “El Tovar” in honor of Pedro de Tovar of the Coronado Expedition. Although Pedro de Tovar had never actually set eyes on the Grand Canyon, he was the one who reported the existence of the Canyon to the Spanish. Early famous guests to El Tovar included Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, playwright George Bernard Shaw, western author Zane Grey, and telegraph inventor Guglielmo Marconi.

Chicago architect Charles Whittlesey envisioned the hotel as a cross between a Swiss chalet and a Norwegian villa, in an effort to appeal to the tastes of the elite at the time who considered European culture the epitome of refinement and class. Unlike later buildings, El Tovar was not meant to blend into the surrounding environment and did not utilize local construction techniques or materials. However, the architect did use natural building materials to complement the hotel’s rustic setting.

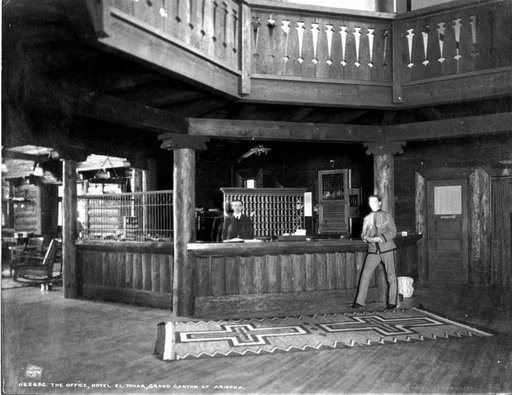

Concrete and rubble masonry supported a wooden frame made of Oregon pine. The first floor had log-slab siding with notched corners to give it the appearance of solid logs, while upper stories had rough weatherboards. The lobby area displayed a peeled log framework, and copper chandeliers decorated the area, paying homage to the importance of that metal in Arizona’s history. Hunting trophies and Native American arts and crafts from surrounding tribes helped give the building some local flair.

Despite its rustic features, the hotel offered many of the era’s most modern refinements. It featured a coal-fired generator that powered electric lights. Furnishing in the guest rooms included sleigh beds and tasteful decorations. Steam heat, hot and cold running water, and indoor plumbing were other luxuries that early visitors enjoyed. However, none of the guest rooms had a private bath in those early years. Instead there was a public bath on each of the four floors that guests could reserve for a small fee.

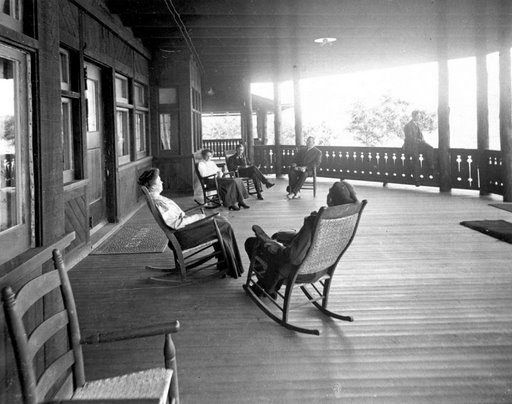

To provide guests with the best meals, the hotel also had a greenhouse to grow fresh fruits and vegetables. A chicken house supplied fresh eggs for hotel guests, and a dairy herd provided fresh milk for the kitchen. Other attractions at the hotel included a barbershop, solarium, roof-top garden, billiard room, and art and music rooms. Guests could purchase works by landscape artists such as Thomas Moran, whom the Santa Fe Railway hired to paint the canyon as a way to advertise it to the nation. Western Union provided telegraph service to the lobby.

In 1922, National Park Service Ranger Michael Harrison began holding a daily lecture illustrated with slides, marking the beginning of Park Service interpretive programs at the Grand Canyon. The dining room featured large picture windows overlooking the Canyon. Harvey Girls, in plain black dresses with white aprons and collars, would welcome guests to dine and treat them with prompt and attentive service.

In 1931 the Santa Fe Railway remodeled the rooms in El Tovar and installed bathrooms in twenty-five of them. Not until 1983 did each room get its own private bath. The concessionaire added a second dining room in 1940 and converted the music room into additional guest rooms. El Tovar was one of the few sites at Grand Canyon to stay open during the years of World War II. The porch on the north side probably dates to the 1950s when the dining room was enlarged and a cocktail lounge was added.

In architectural terms, on a national level El Tovar reflected a transition from constructing ornate Victorian country lodges toward a more naturalistic rustic style that would become the norm at all western National Parks by the 1920s. At the Grand Canyon, construction of El Tovar helped set an informal standard that encouraged visually pleasing and planned development rather than haphazard construction with no uniform appearance. Along with many other buildings in the Grand Canyon Village area, El Tovar today is recognized as a National Historic Landmark.