“God made the Canyon, John Hance the trails. Without the other, neither would be complete.”

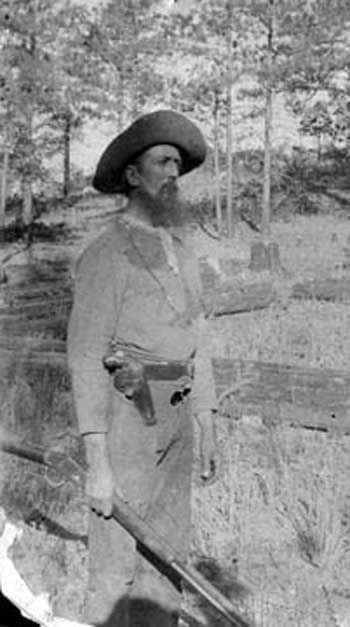

So claimed Bucky O’Neill, a famous early Grand Canyon resident and booster. Today Hance is remembered as an almost larger than life figure whose mining and tourism businesses shaped the course of Grand Canyon history and the use of its environment. Over the span of his 35-year stay at the canyon, Hance built a reputation as an explorer, prospector, entrepreneur, and storyteller for which he is still remembered today.

John Hance was born in 1838 in Tennessee. He fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War and was captured by Union forces and imprisoned briefly before heading west. Though he had been a private in the War, by the time he moved to Kansas in the late 1860s he had adopted the title of “Captain.” In late 1868 he and a brother moved to Arizona to work on a ranch. At some point over the next decade Hance moved to Williams, Arizona, and by 1883 had made his first visit to the Grand Canyon. He established a homestead between Grandview Point and Moran Point, where he built a cabin and water tank near a spring, one of the few water sources on the South Rim. Here he set to work improving a Havasupai trail into the canyon, which became known as the Old Hance Trail, so that he could prospect for ore and mine asbestos.

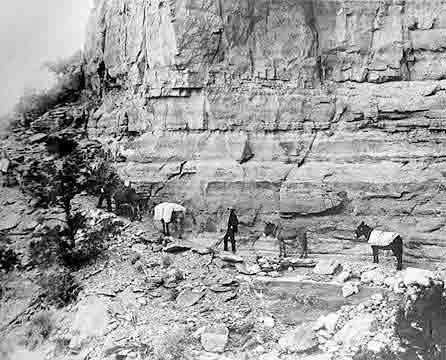

As most prospectors quickly found out, the costs to get any ore they might discover out of the Grand Canyon made mining far too expensive, and many either moved on or turned to other moneymaking ventures. Hance is often cited as the first tour guide at the canyon because he led a party down the Old Hance Trail in 1884. Seeing the money to be made off of curious travelers, he established tourist tents beside his cabin in 1885, making him the first “hotel” operator in the Grandview area of the canyon. Using this trail, he conveyed tourists down to his ranch at the bottom of Hance Canyon. It had steep switchbacks cutting through the more difficult terrain, and once the trail was improved he simply maintained it through use. This old trail was so rough that, as some recalled, he had to lower guests down one section of cliff using ropes.

Despite these difficulties, Hance attracted many famous people from around the country, including artist Thomas Moran, Arizona Senator Henry Ashurst, and Arizona Congressman Carl Hayden, because of his legendary storytelling abilities. Hance is probably the best-known and most beloved of the early storytellers/guides at the Grand Canyon. In some ways, Hance was as much an attraction as the Grand Canyon itself, drawing crowds of interested but wary tourists who wanted to see what tall tales he might concoct. As one visitor famously stated, “Any one who comes to the Grand Canyon, and fails to meet Captain John Hance, will miss half the show.”

By the mid-1890s several washouts and rockslides had nearly destroyed the Old Hance Trail so he abandoned it. In its place he constructed the New Hance Trail, sometimes known as the Red Canyon Trail, to reach his mines in Red Canyon. It served as an important eastern access route to the Tonto Platform for prospectors around the turn of the century. Though Hance alone is often credited with building the new trail around 1894, he may have had help from other miners, who claimed to have helped him build it as the south leg of a 27-mile trail they used in their prospecting activities, though there is no evidence to confirm either story.

Hance used the New Hance Trail to transport copper and asbestos out of his mines in the canyon as well as to entertain tourists. Upon finishing the New Hance Trail he helped build a wagon road from his homestead to the Canyon to help ship out ore and bring in tourists. Guests paid Captain Hance one dollar to walk and two dollars to ride one of his mules down the trail. For $10 he would provide pack animals and his services as a personal guide.

Although it was a new trail, visitors recalled it as just as hazardous and fearsome as the original. Travel writer Burton Holmes in 1904 described his experience after he dismounted his mule to travel the more “awful” sections by foot: “’On foot,’ however, does not express it, but on heels and toes, on hands and knees, and sometimes in the posture assumed by children when they come bumping down the stairs…The path down which we have turned appears impossible…The pitch for the first mile is frightful…and to our dismayed, unaccustomed minds the inclination apparently increases, as if the canyon walls were slowly toppling inwards.”

The trail, which is only one or two feet wide and made of earth and stone, begins about one mile west of Moran Point and descends steeply in a series of tight switchbacks through the Kaibab, Toroweap, and Coconino formations. After this it takes visitors through forest vegetation to the grassy Coronado Butte Saddle in the Hermit Shale formation. From here it drops into a drainage that leads to Red Canyon. Hikers will enjoy the colorful rock layers as the trail follows the east side of Red Canyon and descends through the Supai formation to the top of the Redwall Limestone. Red Canyon contains pockets of layers known as the Supergroup, including bright orange Hakatai Shale, a massive basalt dyke intrusion in this shale, and portions of Bass Limestone containing ancient bacterial mats, which are some of the oldest fossils in the world. At this point the trail drops through steep, short switchbacks through crumbly limestone to the Tonto Platform. The trail crosses the Tonto and then follows the Red Canyon creek bed a few miles to the Colorado River. Just before reaching the river, it intersects with the Tonto Trail at the base of a large sand dune.

In 1895 Hance either leased or sold his property and rights to the New Hance Trail to William Thurber and J.H. Tolfree, but continued to use the ranch and trail to entertain guests and lead tourists into the canyon. As a condition of the transaction, Hance agreed not to open another trail or act as a guide anywhere within 30 miles of that site. Either way, the property reverted back to Hance by 1900 after Thurber and Tolfree ended their tourist operation. Hance patented his homestead in 1907 and soon after this sold it all to Martin Buggeln. In the meantime, his storytelling skills had drawn the attention of the Fred Harvey Company, who convinced him to move to Grand Canyon Village in 1906 or 1907 to be the company’s official tourist greeter. In this role Hance could spin yarns and tell whoppers that entertained guests from around the country. In the meantime, the abandoned New Hance Trail quickly reverted back to wilderness condition since few people used it any longer. Hance died in Flagstaff in early 1919, and was buried at a site east of Grand Canyon Village that today is in the Pioneer Cemetery. Hance’s story in many ways resembles that of William Wallace Bass, a Euro-American entrepreneur in the western portion of the Grand Canyon.

In 1933 Park Naturalist Edwin McKee declared that the New Hance Trail was one of the two worst trails in the Grand Canyon, since in many places it was nearly impassable either by mule or on foot. By the mid-1950s, the NPS considered the trail virtually destroyed. Several sections were completely gone, other portions were barely visible, and some parts had been obscured by wild burro paths. The NPS therefore decided they would not restore it.

The trail might have faded into a distant memory except for a new generation of hiking enthusiasts that sprang up in the 1960s. These hikers used documents and intuition to recreate the trail. By the 1980s the trail had gained a reputation as one of the most challenging backcountry trails in the Grand Canyon and adventure hikers lobbied to keep it open. In 1988 the NPS decided to minimally maintain the trail in the future, but today warns that it should only be attempted by experienced canyon hikers.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Billingsley, George H., Earle E. Spamer, and Dove Menkes. Quest for the Pillar of Gold: The Mines and Miners of the Grand Canyon. GCA, 1997.

- “New Hance Trail.” Grand Canyon National Park. 2008.

- Schullery, Paul. The Grand Canyon: Early Impressions. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1981.

- Stampoulos, Linda L. Visiting the Grand Canyon: Views of Early Tourism. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.