The Hualapai Reservation consists of nearly one million acres in a portion of the Grand Canyon about 50 miles west of the Grand Canyon Village. The Reservation is bounded on the north by a 108-mile stretch of the Colorado River the Hualapai call Hakataya, or “the backbone of the river.” It shares a border to the east with the Havasupai Reservation and stretches to Pearce Ferry near the upper end of Lake Mead to the west. Today much of the reservation is accessible only by dusty, bumpy, unpaved roads, apart from those leading to Peach Springs and the tourist facilities at Grand Canyon West.

Hualapai means “People of the Tall Pines.” The Hualapai are one of numerous tribes in the Yuman language family. Archeological evidence shows ancient ancestors of the Hualapai lived near present-day Hoover Dam as early as 600 A.D. and later moved east along the river. The Hualapai have handed down many stories connecting their history and culture to the Grand Canyon landscape.

For centuries the plants, animals, and landscape of the Grand Canyon and Colorado River provided the Hualapai with food, medicine, and shelter. The Hualapai moved seasonally in small groups, following wild plants as they ripened and preserving some of them to use in the winter. They returned to their villages frequently to tend gardens, and also hunted antelope, mountain sheep, and smaller game. They built small rock diversion dams in creeks to irrigate their gardens. In winter they camped in familiar locations in larger groups.

The Hualapai were part of a vast trading network, and had a great deal of contact with other tribes in the area. They traded beads, horses, and shells with the Navajo and Hopi in exchange for blankets and with the Paiutes and Utes in exchange for guns and horses. They also traded agricultural goods with the Mohave for meat. Hualapai lands contained rich deposits of red pigment that they mined and traded across the region.

Although today they live on separate reservations and although the federal government recognizes them as two separate tribes, the Hualapai and Havasupai are ethnically one people and still intermingle. They also share a common ancestry with the Yavapai, who now live on reservations further south, though the Hualapai considered them enemies.

Spain, then Mexico, and finally the United States all staked imperial claims to the land the Hualapai inhabited. When gold was discovered near Prescott in 1863, it brought a flood of miners and army units to the area. The miners and their herds trampled, ate, and dispersed the wild plants and animals on which the Hualapai had depended. A period of escalating violence on both sides led to the outbreak of the Hualapai War in 1865. This vicious and bloody war lasted several years, during which the Hualapai gained a reputation as fierce fighters. After signing a peace treaty in 1868, some went on to scout for the U.S. Army against their enemies the Yavapai and later the Chiricahua Apache. Most other Hualapai withdrew to their homelands and tried to avoid contact with Euro Americans as much as possible, though miners and military men continued to tresspass into the area.

In 1874, the Office of Indian Affairs ordered the Army to remove the Hualapai south to the Colorado River Indian Reservation in a forced march of nearly 150 miles. Starvation and disease on the reservation drove many to flee and return to their homelands within the year. With their traditional semi-nomadic life no longer possible, many became laborers for Euro American mines and ranches that developed in the region. But at least the Hualapai were home.

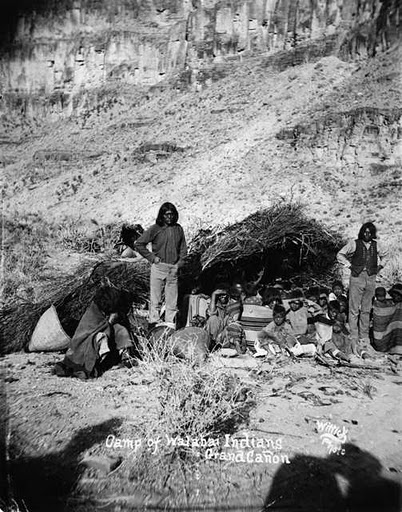

This photograph, taken in 1883, shows a camp of Hualapai near the Grand Canyon. Though they were forcibly removed to a distant reservation in 1874, the Hualapai refused to stay and did whatever they could to return to their homelands at the Grand Canyon.

Credit: Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library

In 1881 members of the tribe asked the US government for a reservation to help protect themselves and their lands. On January 4, 1883, President Chester A. Arthur signed an executive order creating the Hualapai Reservation. About the same time, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad completed tracks across Hualapai lands, tying them into a global trade network. The Railroad diverted Hualapai water sources in Peach Springs, built settlements on Indian land, and otherwise disrupted Hualapai life. However, it also provided employment for tribal members. Later historic Route 66 would follow the railroad’s path through town.

In 1938 the Hualapai approved a constitution and established a governing council, with Peach Springs as the tribal capital. In 1940, following a long fight by the Hualapai, Congress forced the Santa Fe Railway to relinquish their claims to reservation land. A Supreme Court decision the following year upheld this move, finally granting Hualapai clear title to all of their reservation. Principles from this Hualapai land claims case have been adopted around the country and globe to help support numerous other indigenous land claims.

In the 1940s, the Bureau of Reclamation proposed to build a hydropower dam at Bridge Canyon on the Colorado River. At that location the river divides the Hualapai Reservation on the south side of the river from Grand Canyon National Park (formerly the National Monument) on the north side of the river. In the late 1950s, this proposal gained momentum under the Arizona Power Authority. Although the reservoir behind Bridge Canyon Dam would flood Hualapai land along the river, tribal leaders supported it because of the revenue it would bring to the reservation. The Federal Power Commission authorized construction of the dam, which would have provided the Hualapai with one million dollars annually. The 1960s saw the rise of the modern environmental movement and growing opposition to dams on wild and scenic rivers. Protestors concerned about the impact of the dam on the river ecosystem and the Grand Canyon got the project halted. In 1968 Congress passed a law forbidding dam construction within Grand Canyon National Park.

The 1975 Grand Canyon Enlargement Act, which created today’s park boundaries, has led to some conflict between the Hualapai and the NPS, especially over the issue of the reservation’s northern border. The 1883 executive order establishing the Hualapai Reservation identified the Colorado River as the northern boundary of the reservation. The Hualapai interpret this to mean that their boundary is the midpoint of the river. However, in 1976 the federal government argued that the boundary line was the river’s high water mark on the southern shore. The NPS, in an attempt to gain more control over commercial uses of the Colorado River, supports the argument that the boundary is the historic high-water mark, which would eliminate Hualapai access to and use of the river without NPS consent.

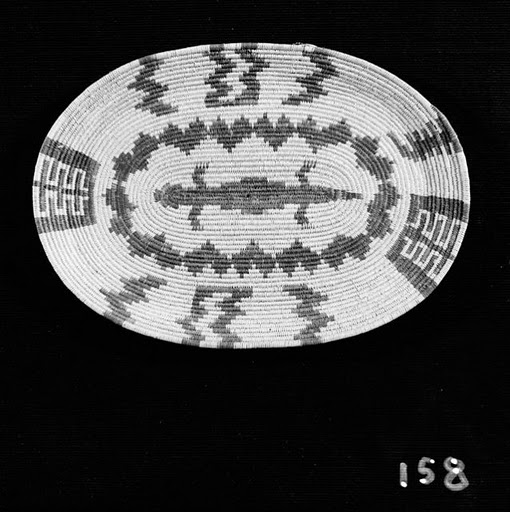

Dottie Crozier Watahomigie, a Hualapai woman who married a Havasupai man, designed and made this elaborate coiled basket in 1932. The sale of arts and crafts such as this helped support tribal members for many years, though now the tribal economy is mostly supported by commercial tourism at the tribe’s rimside development known as Grand Canyon West.

Credit: NAU Cline Library, NAU.PH.99.3.9.4.81

This issue is important to the tribe because of the growing importance of the tourism industry on the reservation. Today many of the approximately 1,500 tribal members rely on the tourism economy, though cattle ranching, timber sales, and arts and crafts still produce some income. In the 1960s a tribal game and fish management program began, which today offers licenses for hunting, fishing, and other recreation activities on the reservation. By the mid 1970s the tribe had established the Hualapai River Runners, the only Native American-owned river rafting company in the Grand Canyon. In recent years the tribe has invested in a number of other business ventures meant to draw tourists to their reservation, including Grand Canyon West—which includes a Native American village, arts and crafts market, song and dance performances, “cowboy entertainment,” and views of the canyon—and the Grand Canyon Skywalk.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

Suggested Reading:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000

- Anderson, Michael F., ed. A Gathering of Grand Canyon Historians. Grand Canyon Association, 2005

- Dobyns, Henry F. and Robert C. Euler. The Walapai People. Phoenix: Indian Tribal Series, 1976.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy. Native Peoples of the Southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000.

- McMillen, Christian W. Making Indian Law: The Hualapai Land Case and the Birth of Ethnohistory. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Shepherd, Jeffrey P. We Are an Indian Nation: A History of the Hualapai People. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010.