There are only a few natural places where the Canyons of the Colorado River surrender their height and allow travelers to pass. On the Colorado Plateau of northern Arizona, where the Echo and Vermillion cliffs converge, sits one of these sites, Lees Ferry. It is here that the foot of Glen Canyon terminates abruptly and the rim drops back down to river level, but the river, ever unyielding, quickly starts to incise Marble Canyon and it disappears back below the rim. This setting — and good fly fishing — attracts people to the area even today.

Through this narrowing in the cliffs, near the confluence of the Paria River and the Colorado River, a parade of Grand Canyon historic characters passed through on their ways to their fortunes, families, churches, missions, and tourism pilgrimages. Lees Ferry has also seen its fair share of those trying to make a living in this high desert – settlers, outlaws, cattlemen, sheep men, prospectors and miners.

Lees Ferry on the Colorado River near the Paria River confluence speaks to the Grand Canyon’s cultural influences and importance as a site deeply entrenched in Mormon culture and regional travel routes. But its link with humans goes back much further. Ancient Puebloan ruins in the area date to around 1125 A.D.

The first Europeans to stumble upon the site were a pair of Spanish priests seeking a northern route from Santa Fe to the mission at Monterey in present day California. Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Fray Silvestre Velez de Escalante attempted the journey in 1776, but running low on food they were forced to turn back in early October. A band of Paiutes had spoken to them of a river crossing in the south which could take them back to Santa Fe.

When they arrived at Pahreah Crossing (present day Lees Ferry), they were not enthused. The river was swift. Two men in the party tried to swim across, and barely made it back to shore with their lives. They were forced to head 40 miles upstream to find safer passage, and crossed the river in Glen Canyon at a site that came to be known as Crossing of the Fathers or Ute Ford. That site is now submerged beneath Lake Powell.

The Echo Cliffs Monocline, a huge fold in Colorado Plateau brings the easily eroded Chinle and Moenkopi formations to the surface, allowing for the rapid end of Glen Canyon and easy access to the Colorado River.

Photo: Emery Kolb. Courtesy of NAU Cline Library, Emery Kolb Collection. Call No. NAU.PH.568.5828

Early boating near Lees Ferry was a precarious business. Many boats washed downstream and were difficult to control.This photo was taken in 1910.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, P. T. Reilly Collection, NAU.PH.97.46.119.41

Read more about the trial of John D. Lee at University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law website, Mountain Meadows Massacre Trial

The first successful recording of a ferry at Pahreah Crossing was in March 1864, when Mormon pioneer Jacob Hamblin and his crew built a raft sturdy enough to carry fifteen men, their supplies and horses across the river. Hamblin and his men made the trip to warn Navajos in what is now eastern Arizona to stop making raids into Utah. However, tensions between the Navajos and Mormons continued to rise. Paiutes also began making raids on Mormon settlements.

Hamblin realized that this crossing, a rare place on the Colorado River that could be crossed, would be the key to Mormon expansion from Utah into northeastern Arizona. He suggested that Mormon church President Brigham Young set up a permanent crossing at this site. The man Young chose to do the job was John Doyle Lee.

Lee was born on September 6, 1812 in Kaskaskia, Illinois. He had followed his church west in 1846, and was a firm believer in his faith. That belief, according to his confession years later, was partly the reason he had participated in the Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857 in which Mormons and Paiute Indians killed 120 Arkansas migrants – men, women, and children – headed for California.

Although tensions between the Navajos and Mormon pioneers making a push into the region from the north in Utah were escalating, Mormon authorities and pioneers continued to move into the territory. During the winter of 1869-70 the Mormons built Fort Meeks near Pahreah Crossing to protect their claimed lands and settlers. In 1874, Mormons built Lees Ferry Fort, at the confluence of the Colorado and Paria Rivers. Lees Ferry Fort, later used as a trading post and school, still stands today.

In 1870, Lee traveled to Pahreah Crossing with an expedition that included Hamblin, John Wesley Powell, and Young. Lee, excommunicated and hiding from the law, was quick to accept an offer to establish a permanent ferry at the site. Lee and his wives Emma Batchelor and Rachel Woolsey and their families moved to the site, building stone and wooden frame homes and a small farm known as Lonely Dell. It was so remote that Lee and his family needed to grow their own foodstuffs to survive.

In January 1873 Lee launched his first barge, the Colorado. When occasional travelers wished to cross the river, they would signal their wishes to Lee by shooting their pistols in the air—a sure way to get someone’s attention. Like many other boats that later would tackle the rapids of the Colorado River, the Colorado was lost later that year as floodwaters pushed it downstream.

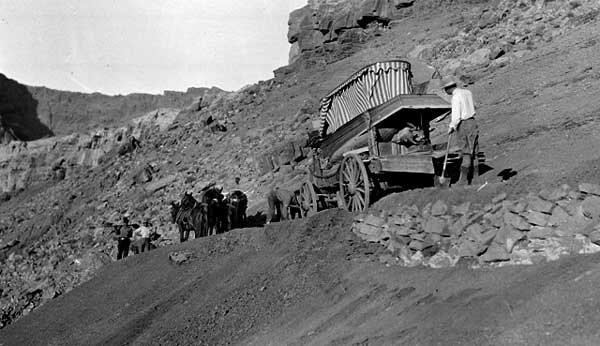

Mormon pioneers poured through Lees Ferry from 1873 to 1875 on their way to settle areas to the south along the Little Colorado River, Salt River, and eventually into Mexico. Perhaps the most common migrant through this area were Mormon couples who were making the long and strenuous wagon trip north along what became known as the Honeymoon Trail to seal their marriages at the Mormon temple in Salt Lake City. Stress between Mormon colonists and Navajos continued to build. The Mormon Church fortified its claim to this important choke point on the Colorado River by building Lees Ferry Fort (still standing near Lees Ferry).

Lee’s past caught up with him in 1874. After 17 years on the run he was captured by Sheriff William Stokes of Beaver, Utah. Lee’s first trial resulted in a hung jury, but his second trial found him guilty of murder in the first degree.

In a published confession to his attorney, Lee wrote,

“I cannot describe my feelings. I knew that I was acting a cruel part and doing a damnable deed. Yet my faith in the godliness of my leaders was such that it forced me to think that I was not sufficiently spiritual to act the important part I was commanded to perform. My hesitation was only momentary. Then feeling that duty compelled obedience to orders, I laid aside my weakness and my humanity, and became an instrument in the hands of my superiors and my leaders.”

Lee was the only man to stand trial for what Brevet Major J.H. Carleton called a “great and fearful crime.” Carleton visited Mountain Meadows in 1859 and described the three burial heaps:

“The wolves had dug open the heaps, dragged out the bodies, and were then tearing the flesh from them. I counted 19 wolves at one of these places. I have since learned from the people who assisted in burying the bodies that there were 107 men, women and children found dead upon the ground. I am satisfied that all were not found. The most of the bodies were stripped of all their clothing, were then in a state of putrefaction, and presented a horrible sight. There was no property left upon the ground except one white ox, which is still at my ranch.”

Lee was sentenced to death, and on March 23, 1877, authorities took him to Mountain Meadows, the site of the killings 20 years earlier. Lee sat on his coffin while the marshal read the death warrant. The condemned man stood, gave his last words, then resumed his perch on the coffin. He was executed by a firing squad of men inside wagons. (Click on photo at leftt for view that includes wagon)

Widow Emma continued to operate the ferry until 1879 when the Mormon Church took over operations and bought her out for $3,000. A succession of families ran the ferry until 1928 when construction of the nearby Navajo Bridge made the ferry obsolete.

Ferrying was not the only means of business at this river crossing. The gold rush that began with Cass Hite in Glen Canyon during the late 1880s had trickled its way south to the crossing at Lees Ferry. Here the American Placer Company, headed by Charles H. Spencer, set down roots in 1910. Spencer was hot for gold, and the Chinle Shale was where he planned to get it. Spencer brought in large boilers, dredges, pumps, flumes, and an amalgamator by early 1911 but met with no success. He needed coal to run his equipment, but the nearest coal seam was 28 miles upstream in Warm Creek. He built a burro trail to haul the coal, but it proved too inefficient.

Investors decided a 92-foot steamboat would improve coal transport and gold production; it was ordered and assembled by late February 1912. Dubbed the Charles H. Spencer, the steamboat performed the way it was supposed to, but it burned most of the coal it transported in the process. Spencer also had trouble with his amalgamator and by 1912 his investors had seen enough and shut the project down. Spencer left, and his boat sank to the bottom of the Colorado River. The Charles H. Spencer is now on the National Register of Historic Places as a shipwreck in Arizona. Spencer returned to the area in the 1960s to mine the element rhenium, which had caused the problem with his amalgamator in the first place, but once again Spencer failed at his endeavor. Lees Ferry was sold to Coconino County in 1910, and was operated by them until 1928.

Today, Lees Ferry is part of the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, approximately one mile upstream from the Grand Canyon National Park boundary. It is the launching point for most river trips within the Grand Canyon. Visitors to the park can decide to take a commercial or noncommercial river trip and can even choose the type of craft and duration of their trip. Visitor usage is highly regulated by the park service, and commercial use for river trips in Grand Canyon is currently capped at 115,500 user days per year. A user day is when one person spends any part of a day on the river. The creation of Glen Canyon Dam has also provided one of the best trout fisheries in the world just upstream from Lees Ferry. It is safe to say that even with the advent of modern technology and engineering, the nature of Lees Ferry still presents one of the best places to witness and view the Colorado River.

Written By Mark Buchanan, Yolonda Youngs, and Patricia Biggs

References:

- Anderson, Michael F. Living at the Edge: Explorers, Exploiters and Settlers of the Grand Canyon Region. Grand Canyon Association, 1998.

- Bradford, James and W.L. Rusho. Submerged Cultural Resources Site Report: Charles H. Spencer Mining Operation and Paddle Wheel Steamboat: Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Edited by Toni Carrel. Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers, no. 13. Santa Fe, New Mexico: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1987.

- Brooks, Juanita. John Doyle Lee: Zealot, Pioneer Builder, Scapegoat. Logan, Utah: Utah State UP, 1992.

- Farmer, Jared. Glen Canyon Dammed. Tucson, Arizona: UP of Arizona, 1999.Grand Canyon: Colorado River Management Plan. Office of Planning and Compliance. United States Department of the Interior, 2006.

- Murphy, Shane, Gaylord Staveley. Ammo Can Interp: Talking Points For a Grand Canyon River Trip. Flagstaff, Arizona: Canyoneers, Inc., 2007.

Website References:

- Carleton, J.H. “Special Report on the Mountain Meadows Massacre.” May 25, 1859. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law, http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mountainmeadows/carletonreport.html

- Lee, John Doyle. “Last Confession and Statement of John D. Lee: Written at his dictation and delivered to William W. Bishop, attorney for Lee, with a request that the same be published.” University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law, http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/FTRIALS/mountainmeadows/leeconfession.html