Though Grand Canyon National Park contains one of the seven wonders of the natural world, crafted over millions of years of erosion and other natural forces, it is capped on either end by huge artificial landscapes that took humans less than two decades to create.

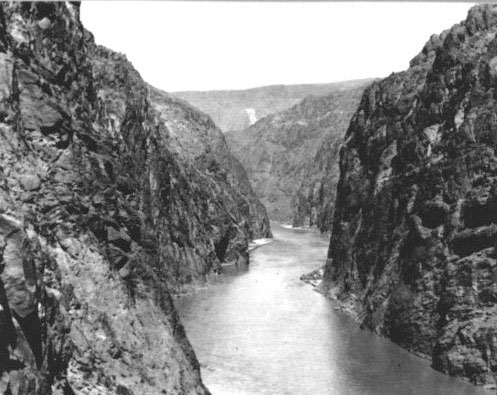

At the southwestern edge of Grand Canyon National Park, on the Arizona-Nevada line, the Colorado River flows into Lake Mead, one of the largest manmade lakes in North America. It began filling upon the completion of Hoover Dam (previously known as Boulder Dam) in 1935. The largest hydroelectric dam in the world at the time of its construction, Hoover Dam was completed in less than five years. It stretches across the Colorado River at Black Canyon, about 30 miles east of Las Vegas. Today Hoover Dam is a National Historic Landmark, and remains the highest concrete arch dam in the United States. The lake that formed behind it is named for Elwood Mead, the head of the Bureau of Reclamation from 1924-1936, who left a major imprint on the water policy and landscape of the West.

Before the dam was constructed, outsiders rarely visited this area because of its extreme temperatures, harsh landscapes, and lack of roads. Still, it was a landscape with significant natural and cultural resources.

The first inhabitants of the area lived between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago, when the environment was wetter and cooler. Over the centuries many different Native American cultures made their homes in the area, some hunting and gathering, others farming. In the 19th century, Euro-American explorers such as Jedediah Smith, Joseph Christmas Ives, and John Wesley Powell traveled through the area.

Once Hoover Dam was completed and the lake filled, however, thousands of tourists suddenly flocked to enjoy the refreshing waters and bask in the steady sun. The Bureau of Reclamation, which built the dam, knew that the lake it created could be turned into a major recreation site, but its focus was on developing water storage projects. Therefore, the Bureau joined forces with the National Park Service, which had experience in recreation management, to develop the area.

In 1936, these two agencies cooperatively created the Boulder Dam Recreation Area, the first national recreation area established in the United States. It included the Hoover Dam itself as well as 25 miles of the Colorado River. Eleven years later, the agencies changed the name to Lake Mead National Recreation Area. In 1950 Davis Dam was completed near Bullhead City, Arizona. This dam and the lake it created, Lake Mohave, were incorporated into Lake Mead National Recreation Area as well.

In 1963 President John F. Kennedy initiated the policy that Congress must establish all future National Recreation Areas (NRAs), and the next year Lake Mead National Recreation Area became the first such area established by Congressional statute. Today, out of 43 NRAs, the Park Service administers 20, most of which are centered on large reservoirs that emphasize water-based recreation. Other agencies, including the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, administer the 23 other NRAs.

Lake Mead NRA contains 1.5 million acres, making it twice the size of Rhode Island. It has about 550 miles of shoreline, though the area covered by water comprises less than 13 percent of the total area of the NRA. It also includes nine designated wilderness areas, as shown in the NPS diagram at right.

Part of the NRA overlaps with portions of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, created in 2001, on the Arizona Strip. Although most of the eight million visitors it attracts every year see it purely as a recreation spot, the lake is actually a giant reservoir, storing water that is delivered to farms, homes, and businesses in Nevada, Arizona, California, and Mexico.

The Mojave, Great Basin, and Sonoran Deserts, three of the four American desert ecosystems, all intersect at Lake Mead Recreation Area. Elevations within Lake Mead NRA range from about 500 feet to nearly 7000 feet above sea level. Temperatures in the summer can easily reach over 110 degrees, though winters are mild.

Even though the land is arid and hot, it is home to a surprising array of birds, mammals, fish, and reptiles. These include bighorn sheep, kit fox, ringtail cats, desert tortoise, chuckwalla lizards, Gila monsters, and several kinds of rattlesnakes. Though the cacti and creosote that dot the landscape may make it seem barren, in the springtime it comes alive as rain showers spur the growth of colorful wildflowers.

The history of Lake Mead NRA intersects with that of Grand Canyon National Park just as its ecosystem does. For instance, in 1953 Lake Mead NRA was the site of the first concessionaire-operated trailer park within the National Park System. The NPS in the 1950s was looking for a way to serve the growing number of tourists coming to visit sites within the national park system, and kept an eye on this site to see whether a similar system could be implemented in other parks. The experiment was successful, and in 1961 Grand Canyon National Park became the first park to open this type of facility.

Lake Mead NRA offers many year-round activities for visitors. Its lakes provide opportunities for boating, swimming, and fishing, while wilderness areas appeal to hikers, photographers, and sightseers just passing through. Most of the water activities take place along 20 miles of the southwestern shore, the strip most accessible from Las Vegas. Because it was artificially formed in a desert and canyon landscape, the sapphire blue waters of the lake tend to lap up against steep red and white cliffs, making most of the lake area accessible only by boat. Most of the land elsewhere in the NRA is a typical desert landscape of dry washes and low barren hills.

Though Lake Mead NRA provides water and recreational resources for millions of people, this enjoyment came at the expense of many important cultural and natural resources. With the creation of Lake Mead, plants were washed away, animals lost their habitat, and people were driven from their homes. When Lake Mead filled, it covered a significant salt mine in the valley of the Virgin River that had been utilized for centuries by Native Americans in the Grand Canyon region.

The town of St. Thomas, founded in 1865, was inundated by the lake waters. When construction on Hoover Dam began, the government posted evacuation notices for five years to give residents ample warning that their community would soon be under water, but few left until they actually saw water rising in the canyon. In 1938, the last citizen rowed away from his house. Occasionally when lake waters get low, people can still see buildings and rusted machinery from this underwater ghost town. Lake Mohave similarly flooded a large segment of the Mohave Desert, submerging many canyons, settlements, and archeological resources.

More than 90 percent of the water in Lake Mead comes from rain and snowmelt that travels down the Colorado River and its tributaries from Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming. The area comprising Lake Mead NRA itself usually gets less than five inches of rain each year. With many parts of the West suffering from a protracted drought since 1998, the water level in the lake has been steadily decreasing except for a small spike in 2005.

Currently, the water level in Lake Mead is at its lowest point in over 40 years. The Bureau of Reclamation claims that this is the way the reservoir is designed to function—in a cyclical pattern with periodic wet years filling it to capacity followed by a series of dry years and declining levels, then another wet spell that fills it again. Global climate change, however, is resulting in less snow and less water in the Colorado River than at any time in recorded history. This reduction in supply coupled with greater demands and diversions for cities and farms is posing unprecedented challenges for Lake Mead and for water managers throughout the Colorado River Basin. Scientists Tim Barnett and David Pierce of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography have suggested that Lake Mead could run dry as early as 2021. As of April 2009, the Bureau of Reclamation reported that the lake is at 46 percent capacity.

Low reservoir levels threaten not only the water available for humans, but also the ecosystem that has developed within and around the vast Lake Mead National Recreation Area. As with all public lands, it is the responsibility of the American people who own them to use them wisely and sustainably so that future generations will be able to enjoy these natural and cultural resources.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.

- Barnett, Tim P. and David W. Pierce. “When Will Lake Mead Go Dry?” Water Resources Research 44 (29 March 2008).

- Billingsley, George H., Earle E. Spamer, and Dove Menkes. Quest for the Pillar of Gold: The Mines and Miners of the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon Association, 1997.

- Bureau of Reclamation Hoover Dam website: http://www.usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/index.html

- Lake Mead National Recreation Area website: http://www.nps.gov/lame