The word “fire” sparks both awe and fear in humans. Fire is an element of nature, triggered by lightning strikes and essential to the propagation and health of many plant and animal species. For centuries, natural fires helped to thin competing species, recycle nutrients into the soil, aid wildlife by increasing forage and habitat, and by creating openings in forest canopy to allow sunlight to reach the ground. Flora and fauna adapt to the pattern of fires. Changing that pattern can be as ecologically disruptive as changing the pattern of rainfall.

However, fire is also cultural, since it is one of the earliest and most prolific tools of humans. As fire historian Stephen Pyne says, “Unlike floods, hurricanes, or windstorms, fire can be initiated by man; it can be combated hand to hand, dissipated, buried, or ‘herded’ in ways unthinkable for floods or tornadoes” (Pyne 1982: 3-4). Fire has played a major role in massive cultural changes: it helped hunter-gatherers entice and encircle big game; it helped early agriculturalists quickly clear the land; and it helped power the engines of the industrial revolution. Interacting with nature’s fires, human ignitions have long been a significant component of wildfire history and consequently have helped shape ecosystems. Still, not all fires are benign. Fire can be a dangerous and unpredictable threat to life and property.

Though the Grand Canyon is recognized for the geological forces that created its landscape, these natural changes took eons to unfurl. Fire and fire suppression has caused much more noticeable and dramatic changes to the landscape in the human time scale. For instance, much of the montane forests of the North and South rims in prehistoric times resembled a savannah, with large swaths of grasses dotted with mature ponderosa pine and other fire resistant species. Frequent lightning-caused and human-caused fires thinned the forest by killing many younger trees but usually sparing the large, thick-barked trees. Repeated fires also encouraged grasses to grow by recycling nutrients and stimulating new growth. However, as Euro Americans entered the area in large numbers, they changed the existing environment, including its fire regime. A combination of fire suppression, grazing, and other human uses impacted the landscape in profound ways. On the North Rim in the 20th century, fire suppression allowed the native conifer trees to proliferate, choking out other kinds of vegetation by forming a dense canopy above and by coating the ground with pine needles below. Heavy grazing reduced the dry grasses that could carry small fires close to the ground. As a result, young trees survived and grew close together while on the forest floor pine needles and dry branches accumulated into a thick flammable duff. When these forests burned, they burned hot and destructive.

These changing natural conditions along with a cultural fear of fire have posed a thorny problem for administrators at Grand Canyon National Park over the past century. The attempt to exclude fire ironically led to conditions that caused much more damaging burns, which only strengthened the policy of fire suppression. But where fires were kindled by lightning, this suppression policy seemed to violate the Park Service charge to preserve the natural order so far as possible. Accordingly, the National Park Service, as America’s premier preserver of both nature and culture, began to struggle with questions about the proper place of fires in “wilderness” areas: should fires be allowed to burn freely as they would in nature, should they be eliminated as quickly as possible, or should the NPS seek a middle path balancing the human desire to control fire with the desire to let fire to play its natural and beneficial role in shaping ecosystems?

The past century has thus witnessed changes in fire policy and practice. The Forest Service, the original federal managers of the Grand Canyon, was first charged with protecting the forests in the area. At the beginning of the 20th century, forest managers across the country viewed fires as destructive and embarked on an aggressive policy of suppression. The early Forest Service was driven by a desire to eradicate fire entirely from their forests.

By 1919 the Forest Service had established fire lookout towers at Hopi Point, Bright Angel Point, and Grandview. After Grand Canyon became a National Park, the NPS continued the Forest Service’s policy of fire suppression. In fact, the arid climate and vast wooded areas on the park rims has led its administrators to create one of the most active fire management programs in the national park system. The NPS saw forests as natural treasures that needed to be preserved; if fires were allowed to burn them, something irreplaceable would be lost forever, they believed. Therefore, until the 1960s the NPS and conservationists for the most part agreed that fire protection was imperative. Fire control took precedence over every other activity apart from protecting human life.

The North Rim Lookout tower. Originally constructed in 1928, the CCC moved this tower to its current location at the north rim entrance in 1933. Four Grand Canyon fire lookouts were added in 2009 to the national historic lookout register. To read about these historic lookout towers, see: http://www.nps.gov/grca/naturescience/cynsk-v13.htm

Photo: Dave Lorenz

The NPS made an agreement with the Forest Service to cooperate in keeping fire lookouts manned and operational, and to jointly fight fires regardless of jurisdiction. In 1919, the NPS built an additional fire lookout at Signal Hill. Every summer, park rangers would be assigned to these towers as part of their duties. If anyone spotted smoke they used the other towers to triangulate the location of fires, then report it to the park superintendent using single strand phone wires so that firefighters could be dispatched and burns contained as quickly as possible. Rangers conducted fire training for park residents, developing a formal fire control plan by 1929.

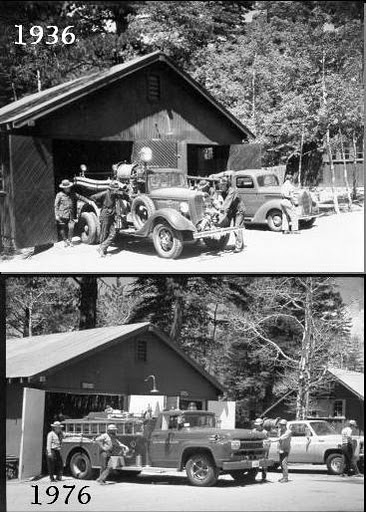

The arrival of Civilian Conservation Corps workers at the park changed the firefighting landscape but did not change the underlying philosophy of fire suppression. These CCC men took over the role of manning lookout towers, freeing rangers for other tasks. On the North Rim, CCC workers constructed residence houses, warehouses, maintenance shops, and a fire cache. They also improved and constructed miles of roads, making it easier for firefighters to reach remote sites. They constructed a permanent fire tower and moved another lookout to a better location, and in 1936 built a network of tree towers with scaling ladders to help more precisely pinpoint the location of fires along the densely forested rims. They erected telephone lines to help connect these towers to dispatchers who could send responders—many of whom were CCC workers—out much more quickly. They developed water holes for use in firefighting and cleaned up roadside fire hazards. Much of the firefighting infrastructure on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon for decades was a legacy of these CCC crews. Even into the 1980s, summer firefighting crews lived in the same houses, utilized the same cache, maintained the same remote roads, and manned the same towers.

Through the 1920s-1950s, firefighting efforts became more intense, scientific, expensive, and sophisticated. The NPS completed a “fire atlas” in 1935 and had telephones and field radios installed in 1937 for faster communication and more accurate pinpointing of fires. During WWII, the CCC left, and park rangers again took control of fire management. In the late 1940s “fire control aides” (or “smokechasers”) took over the duties of manning lookout towers and fighting fires, sometimes living in a tent cabin at the base of a watchtower to stay as vigilant as possible. Planes patrolled the Canyon for fires by 1949, and the NPS adopted a “central forest fire dispatching system” in 1951, with ground-to-air communications established in 1952. Superintendent Harold Bryant was pleased to record in the early 1950s that fires burned an average of less than one acre in a thousand annually, unaware that achieving the decades-long goal of near-total suppression had radically altered forest ecology and created conditions for subsequent catastrophic high-intensity fires.

Fire historian Stephen Pyne, who worked as a firefighter in the Grand Canyon for 15 summers starting in 1967, recalled that in his first years the fire crew, when supplemented by a squad of Southwest Forest Fire Fighters, was the largest collective entity on the North Rim—there were more firefighters than even NPS rangers and maintenance crews. When not actively fighting fires, crews were kept busy clearing and rebuilding roads, cutting wood for campgrounds, cleaning up hazardous trees along main roads, and maintaining equipment—in effect a seasonal replacement for the CCC. Fire crews experienced rapid turnover, with seasonal workers rarely coming back for more than four summers. Firefighters had to be in good enough physical shape to carry a firepack, tools, saw, and canteens up and down the steep ridges and ravines of the rim.

In the early 1970s, well-known environmental writer Edward Abbey worked in a fire lookout tower on the North Rim. As he described it: “One entered through a trap door in the bottom. Inside was the fire finder—an azimuth and sighting device—fixed to a cabinet bolted to the floor. There was a high swivel chair with glass insulators, like those on a telephone line, mounted on the lower tips of the chair’s four legs. In case of lightning. It was known as the electric chair” (Abbey, 1979: 177). He lived in an old CCC cabin near the entrance station with other fire crewmen, or sometimes in a trailer next to the cabin, near the tower. After Abbey’s final season, the NPS stopped manning the towers and instead began relying solely on aerial fire reporting.

By the late 1960s, environmentalists were beginning to embrace the idea that wildlife management meant protecting natural ecological processes, not just its individual components. Therefore, they argued, national parks should try to return fire to the ecosystem and attempt to restore the environment to the state it was in before the arrival of Euro Americans. At the same time, scientists began to take greater interest in the topic of fire ecology, with important environmental scientists such as Starker Leopold calling for a return of fires to the land, especially to national parks. Fire control slowly came to be seen as unnatural and counterproductive to the mission of the parks. Fire suppression declined in importance as a priority of park management, and firefighting crews decreased in numbers.

In the 1970s most scientists and environmentalists agreed that fire needed to be reintroduced to the landscape, but they were not sure how since forests had so much woody fuel buildup after a century of fire suppression. A consensus developed around the idea of intentionally igniting controlled burns (a “prescribed” fire) based on comprehensive fire management plans for each forest and park. NPS fire managers agreed that the judicious use of “prescribed” burning could begin to reduce fuel loads in the forests during times of year when moisture and humidity minimized the risk of a catastrophic fire. In 1978 Grand Canyon National Park officially adopted a policy supporting prescribed burns. It was easier said than done, though. As Stephen Pyne has observed: “As fire management is redefined by the Park Service, it becomes a compromised and ambiguous job. Emergent philosophies of fire management demand not only a retreat from traditional fire suppression, but a complicated program of fire reintroduction that will, until the system is mastered, involve difficult decisions and a quota of public relations fiascos” (Pyne 1989: 187).

In the 1980s, forest fires around the country, particularly the 1988 fires at Yellowstone National Park, brought awareness of the debate over western fires into the public eye like never before. Many Americans were aghast at the size and destructiveness of the Yellowstone fire. The fire community itself was divided over whether humans should be in charge of fire, or whether it should be left to nature as much as possible. Joining into the outcry were local citizens who watched with fear as fires licked at the doors of their homes and property.

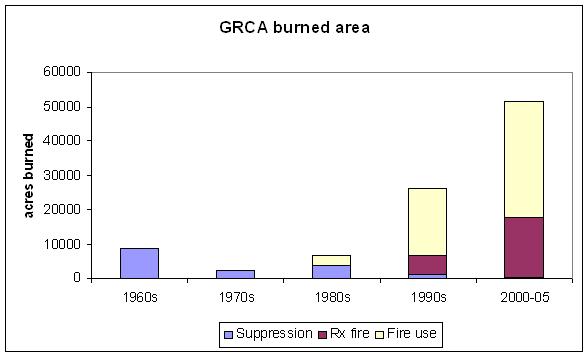

With the 1988 Yellowstone fires in mind, NPS managers at Grand Canyon adopted a new fire plan in 1992 and began more aggressively using fire as part of its management practices. Many prescribed burns were started across the park, though many of these proved difficult to control. As the adjacent graph shows, the NPS not only intentionally set many fires (called “Rx” in the graph) since the 1990s, but they also allowed many lightning-caused fires to burn relatively freely (called “Fire Use” burns in the graph). According to Pyne, “Probably 95% of the area burned since the park’s creation in 1919 burned in the 15 years that followed the 1992 plan” (Pyne, 2007: 8).

Since 1992, every few years park administrators develop and update a Fire Management Plan that helps define activities for the 1.2 million acres in the park to keep their policies in accordance with federal guidelines and local stewardship objectives. Today fires in Grand Canyon National Park are handled according to a 2005 Fire Management Plan. Staff in the Fire and Aviation Branch are responsible for managing fires in the park. Crews work to keep park buildings clear of brush and other flammable debris, and suppress dozens of wildfires every year. Aircraft patrols help rangers keep an eye on the Canyon’s forests and grasslands. Fire managers use prescribed burns to reduce dangerous accumulations of dry underbrush and other materials that could ignite in a flash, endangering natural and cultural resources. Managers carefully evaluate wind conditions, temperatures, weather patterns, and other variables before starting such burns to make sure that they will be able to control the situation as much as possible.

With the 1988 Yellowstone fires in mind, NPS managers at Grand Canyon adopted a new fire plan in 1992 and began more aggressively using fire as part of its management practices. Many prescribed burns were started across the park, though many of these proved difficult to control. As the adjacent graph shows, the NPS not only intentionally set many fires (called “Rx” in the graph) since the 1990s, but they also allowed many lightning-caused fires to burn relatively freely (called “Fire Use” burns in the graph). According to Pyne, “Probably 95% of the area burned since the park’s creation in 1919 burned in the 15 years that followed the 1992 plan” (Pyne, 2007: 8).

Though fire science has greatly advanced over the past century, the management of fire in national parks is still a complex issue. The long drought that has hovered over the Southwest in recent years—drying up water sources, desiccating plants and shrubs, and sparking more wildfires—adds yet another layer of difficulty. It will likely take many years to undo the disruption humans have caused to the fire ecology of the region over the past century, and some people question whether it will ever be righted.

Furthermore, even the most carefully watched fires can sometimes get out of hand, such as the 2000 Outlet Fire, a prescribed burn on the North Rim near Point Imperial that escaped control, blackening over 14,000 acres and forcing evacuations and closures of some park areas for weeks. In the meantime, scientists and managers continue to study the use and impact of fires in an attempt to balance the natural and cultural fire needs at Grand Canyon National Park.

With the 1988 Yellowstone fires in mind, NPS managers at Grand Canyon adopted a new fire plan in 1992 and began more aggressively using fire as part of its management practices. Many prescribed burns were started across the park, though many of these proved difficult to control. As the adjacent graph shows, the NPS not only intentionally set many fires (called “Rx” in the graph) since the 1990s, but they also allowed many lightning-caused fires to burn relatively freely (called “Fire Use” burns in the graph). According to Pyne, “Probably 95% of the area burned since the park’s creation in 1919 burned in the 15 years that followed the 1992 plan” (Pyne, 2007: 8).

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Abbey, Edward. Abbey’s Road. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979.

- Anderson, Michael F. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.

- Pyne, Stephen. “Friendly Fire,” 2007.

- Pyne, Stephen. Fire on the Rim: A Firefighter’s Season at the Grand Canyon. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995.

- Pyne, Stephen. Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Rothman, Hal. Blazing Heritage: A History of Wildland Fire in the National Parks. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Canyon Sketches Vol 13 – Sept. 2009: http://www.nps.gov/grca/naturescience/cynsk-v13.htm