Crystal Rapid is one of the most feared and respected rapids on the entire Colorado River. Located at river mile 98, Crystal is a highlight of most modern river rafting trips in Grand Canyon. It is created by Crystal Creek, named for its clear water, which enters here on the north side of the Colorado River, and by Slate Creek which enters the river from the south. It is one of only a few places within the Grand Canyon where two side canyons converge at the same point on the river. This type of natural setting tends to create some of the most technically difficult rapids for river runners, and Crystal is no exception. Here, two debris fans enter the river at the same spot, and constrict its natural flow into a roiling rapid. This rapid presents many obstacles to river runners, and the consequences of any mistakes could be deadly.

In 1915, Crystal Rapid dealt some unexpected trouble. Charles Russell, a mine promoter from Prescott, Arizona, ran the Grand Canyon in 1908 to look for mineral deposits. Unsuccessful, but not defeated, Russell again attempted the canyon in 1914, but for a different purpose. The Kolb Brothers produced a movie of their 1911-1912 river trip through Grand Canyon, and turned a good profit showing it at venues across the country. Russell saw it and dismissed it as amateur. He did not have any prior filmmaking experience, but he thought he could produce a better film. He spent $5000 on camera equipment, and hired an expert river man, Bert Loper, to help him run the river. They set off from Green River, Utah on June 19, 1914, and what followed became a comedic disaster.

The trip went downhill fast. Russell sunk one of their two boats at Rapid 14 in Cataract Canyon. They stored their surviving boat and camera gear on the bank and hiked out. Loper quit. Unfazed, Russell stole one of Loper’s new boats, the Ross Wheeler, and managed to hire two more men, Bill Reeder, a local man from Green River, and August Tadje, an amateur filmmaker, each with even less experience than Russell at running rivers. They started anew back at Green River, and once they recovered the boat Loper and Russell stored, they quickly managed to sink it in the exact same spot as the first boat. Once again they hiked out. Reeder quit, and Russell went to Salt Lake City to order a new boat, aptly named, the Titanic II. This third boat fared no better. They managed to make it to the Upper Granite Gorge in Grand Canyon before it broke loose in an eddy and drifted away. For a third time Russell hiked to the top of the canyon, this time by means of the Bright Angel Trail. Russell phoned Saint Louis for yet another steel boat. Without the luxury of the Green River launch point, all sixteen feet of this new boat needed to be rolled down the Bright Angel Trail on a makeshift wooden dolly. It took one week to roll the cart eight miles to the river.

Finally reaching Crystal Rapid, seven months after the beginning of their initial trip, Russell felt good. He successfully lined and portaged some major rapids just before his arrival and had regained some confidence. He wanted to get a good shot of the Ross Wheeler coming through Crystal, so he took the oars of his new boat in hand and set off down the rapid with his camera equipment. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, Charles Russell’s bad luck held. He lodged the boat in between two huge boulders at the lower left end of the rapid. The boat did not sink. The weight of the water pinned the boat against the rocks. Back to the rim, and they did not have the luxury of a trail this time. Nearly dying from his trek, Russell managed to stumble west to William Bass’s hotel. He rented a windlass, ropes, and grappling hooks to remove his boat from the boulders. Back at the river they freed the boat, and Russell at the oars again got it stuck between more boulders in the same rapid! Thankfully they had yet to return the equipment. The second retrieval finally broke Russell’s spirit. The hooks tore right through the side of the boat, and it, along with all the camera gear, sank to the bottom. Charles Russell had enough. He took whatever dignity and money he had left, rowed to the foot of the South Bass Trail and hiked out for good. He left his one surviving boat, the Ross Wheeler, tied to shore.

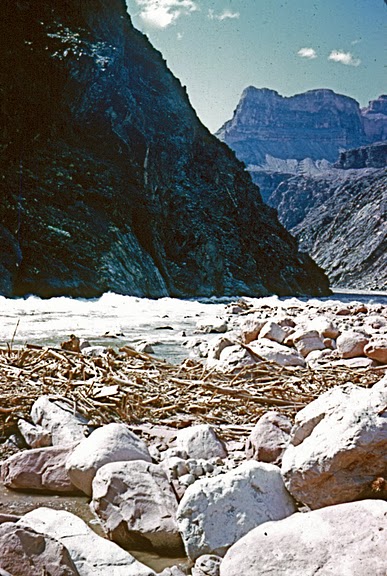

Surprisingly, the Crystal Rapid that Russell faced was a riffle compared to the raging stretch of whitewater it is today. The canyon is an ever-changing place, and Crystal Rapid happens to be the site of the largest geomorphic channel change along the Colorado River in the last several hundred years. In December 1966 a storm unlike any witnessed before, dropped over 14 inches of rain in some places along the north rim. All this water sent debris flows crashing down side canyons. Prospect, Nankoweap, Bright Angel, and Lava-Chuar Canyons all experienced them, but none as large as the one that came down Crystal Canyon. During that December storm Clear Creek flowed at a rate of 10,000 cubic feet per second! An impressive statistic considering the average annual flow for the Colorado River is around 11,400 cubic feet per second. A river of mud literally blocked the Colorado River. When the storm had passed, the debris fan constricted the Colorado to less than a quarter of its original width, and a large boulder at the top created one of the largest holes on the river.

In June of 1980 Lake Powell filled for the first time. For the Bureau of Reclamation a full reservoir was an ideal reservoir, so they kept it that way. In the spring of 1983, officials left enough room in the reservoir for the average annual runoff to completely fill it, but that year proved anything but average. A cool spring, combined with a heavy snowpack, meant the bureau had to deal with the king of all floods by late June. They had so much water coming into Lake Powell that the operations manager at Glen Canyon Dam, Tom Gamble, needed to place plywood across the top of the spillway gates to keep the water from overtopping them. The Bureau’s nightmare translated into one wild ride downstream. At Crystal Rapid a flow of 70,000 cubic feet per second birthed a standing hydraulic wave that ran across the river. The three-story behemoth flipped boats left and right, and many people died. For the first time the Park Superintendent was forced to close a stretch of the Colorado River, and did not allow passengers to run Crystal Rapid.

The rapid changed after the flood, and so did management at Glen Canyon Dam. At Crystal Rapid a large amount of debris had washed downstream of the newly formed delta, and created the rapid’s latest obstacle, the “rock garden.” The rapid is still changing, but will likely remain the greatest challenge to river runners at Grand Canyon. It is said that Crystal Rapid has caused more damage and death than any other rapid in Grand Canyon, and yet for some reason boatmen still dream of the chance to test their skills at Crystal. It is truly an amazing place, and one that most river runners never forget.

Written By Mark Buchanan

References:

- Lavender, David. River Runners of the Grand Canyon. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1985.

- Magirl, Chris, Bob Webb. “The Changing Rapid of Grand Canyon – Crystal Rapid,” boatman’s quarterly review volume 15, no. 2 (Summer 2002).

- Martin, T. and Whitis, D. Guide to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon: Lees Ferry to South Cove. Fourth Edition. Flagstaff, Arizona: Vishnu Temple Press, 2008.

- Murphy, Shane, Gaylord Staveley. Ammo Can Interp: Talking Points For a Grand Canyon River Trip. Flagstaff, Arizona: Canyoneers, Inc., 2007.

- Steiger, Lewis. “Speed,” in There’s This River… Grand Canyon Boatman Stories, edited by Christa Sadler. Flagstaff, Arizona: This Earth Press, 2006, 155-180.

- United States Department of the Interior, Operation of Glen Canyon Dam: Final Environmental Impact Statement, Record of Decision, Appendix G. Approved by Sec. of Int. Bruce Babbit, October, 1996. pp. Appendix G-6