Christa Sings

River Running in the Grand Canyon has always been a mixture of daring, good luck, and stamina. Such was the case for one of the earliest and most celebrated river runners, geologists, and ethnographers—John Wesley Powell. Powell was only 35 years old when he led this monumental trip down almost 1,000 river miles but he made up for his youth in determination to explore the river. Powell was a curious man, intrigued by all aspects of natural science and the opportunity to explore the river beckoned him during his field trips to the region.

He was also a daring man. He had served in the military during the Civil War and lost his right arm during battle. He returned to battle several times after this loss but eventually left the service in 1865 to accept a position as Professor of Geology and the Museum Curator at the Illinois Wesleyan University. Not one to remain stationary for long, Powell soon began plans for a river expedition. In 1869, Powell embarked on the first of two journeys down the Colorado River to explore its watery course and document his findings. Before his trip, few Euro-Americans knew of the canyon and rumors of its existence remained undocumented. That soon changed.

On May 24, 1869, Powell’s small group launched their trip from Green River, Wyoming, destined for a river wilder than anyone could have guessed.

On May 24, 1869, Powell’s small group launched their trip from Green River, Wyoming, destined for a river wilder than anyone could have guessed.

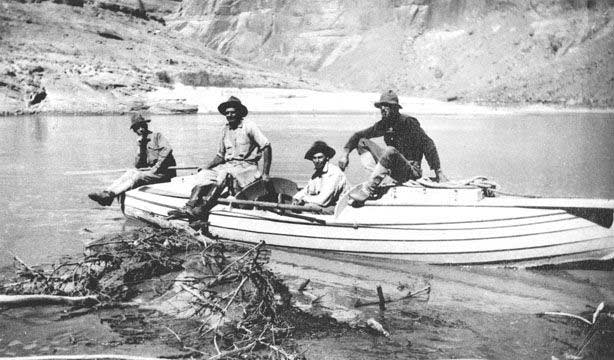

Powell (shown in photo at age 35) assembled ten men and four wooden boats stocked with enough provisions for several months of travel. The trip was full of danger as well as adventure. Part of their challenges came from the extent and size of the rapids along the Colorado River. The men encountered rapids larger than their boats could manage so Powell instructed the men to portage their boats around the turbulent waves – a process that took many hours and tremendous effort. The group also faced diminishing provisions, the challenge of rowing through uncharted waters, and their own fears of what lay around the next bend in the river. However, they persevered and two months later emerged from the canyon at the Virgin River almost 1,000 miles from their starting location. Powell, at once satiated from the trip but also spurred to return to the canyon once again, began to prepare for a second trip down the frothy waters of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in 1871.

Powell was better prepared to handle the Canyon’s challenges on his second trip down the Colorado River. His first trip in 1869, barely three-and-a-half months, had been more ordeal than exploration. For his second trip, which was sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, Powell arranged to have supplies brought down to the river at various points to avoid the privations of the first expedition. The second trip began at Green River, WY, on May 22, 1871. The party descended more than 700 miles of river, to Lees Ferry (the beginning of the Grand Canyon) where Powell halted for the season on October 26. For the next nine months, Powell and his crew surveyed the Kaibab Plateau and made extensive contacts with the indigenous peoples of the region. The party resumed their river trip on August 1, 1872, and ended the expedition at Kanab Creek five weeks later.

Whereas Powell’s 1869 expedition was high adventure full of danger, the second trip was organized to focus on scientific and ethnographic study of the river, canyons, plateaus, and peoples. Powell engaged a succession of photographers: E. O. Beaman, who stayed with the party until January 1872, James Fennemore, who worked with Powell on the Kaibab Plateau surveys, and John K. (Jack) Hillers who was the photographer of the last leg of the journey through the Grand Canyon. Powell also hired 17-year-old Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh as a boatman and as the artist for the expedition.

When Powell published his accounts of the exploration of the Grand Canyon, beginning in 1875, he deliberately blurred the two trips into one–writing as if there had been a single trip in 1869. He never wrote about the second trip separately or mentioned the men who accompanied him on that expedition. No one wrote an account of the second Powell expedition until Powell’s artist Frederick Dellenbaugh penned The Romance of the Colorado River in 1902 and A Canyon Voyage in 1908. Dellenbaugh’s books, with extensive discussion of the river and its rapids, became the bibles for the next generation of river runners; they also provide excellent information on the men who made the trip and their contributions to Powell’s success. Although Powell never used any of Dellenbaugh’s art in his publications (preferring the better-known Thomas Moran and the photographs of Jack Hillers), Dellenbaugh’s art speaks for itself in his books.

Powell’s own writings began with a series in Scribner’s Monthly in 1875, and followed in that same year with his Report of the Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and its Tributaries (Smithsonian Institution). Two decades later it was revised and re-published as The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons, available today online by the Gutenberg Project under the title Canyons of the Colorado: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8082

It was through this account—in pictures, maps, and words—that knowledge of the vast extent, geological complexity, and massive proportions of the Grand Canyon gained popularity throughout America and internationally.

Although Powell popularized knowledge and sparked curiosity about the Grand Canyon with publications, maps, and photographs from his expeditions, the Colorado River remained an area traversed by Native Peoples and Euro-American trappers and miners more than tourists in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Emery Kolb (left) and Frederick Dellenbaugh (right) at the John Wesley Powell memorial at Powell Point on the South Rim, taken in 1921 at an event to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Powell’s second expedition down the Colorado River. The flag is from Powell’s boat, the Emma Dean, and the book sitting on the flag is a copy of Dellenbaugh’s A Canyon Voyage—the very same book that the Kolb Brothers used on their 1911-1912 river trip through the Grand Canyon.

Photo: National Park Service, Grand Canyon Museum Collection, GRCA-5533.

Nathan Galloway was a hardy soul who quite literally turned river running in the Grand Canyon around. He revolutionized early river running by piloting a lightweight, flat-bottomed boat down the Colorado River—backwards.

The common practice of the day for river runners involved rowing heavy, wooden boats forward into the churning rapids. Galloway realized that if he entered the rapids with the back of his boat, or the stern, first and rowed upstream he would have greater control of the craft—and hopefully his fate—in the rapids. His boat and new “stern first” technique soon caught on as miners and trappers adopted it for their travels along the river.

In 1909, Galloway’s boat and technique caught the eye of mining financier Julius Stone who proposed a trip starting at Green River, Wyoming down the Colorado River. Starting in September of that year, they emerged three months later at Needles, California as the first group to float the river for pleasure.

Ellsworth and Emery Kolb were no strangers to feats of daring. The two brothers were pioneer photographers in the Grand Canyon and some of the earliest year-round Euro-American residents on the South Rim. They ran a successful photo studio on the South Rim of the Canyon and often made forays along the trails and recesses of the canyons pursuing new views to sell to canyon tourists.

Hearing of the success of Nathaniel Galloway’s boats on the river and inspired to film the same stretch of the Colorado that John Wesley Powell had floated, the brothers built Galloway-inspired boats of white cedar and oak. They named their crafts Edith (after Emery’s daughter) and Defiance. In the winter of 1911-1912, the two brothers floated down the river for 101 days and became the first river runners to record their exploits on film. The brothers showed the film daily in their studio. Although Ellsworth left the Canyon for Los Angeles in 1913, Emery continued showing the film in Kolb Studio until his death in 1976.

The original film is hosted by Northern Arizona University’s Cline Library with the recorded narration given by Emery Kolb.

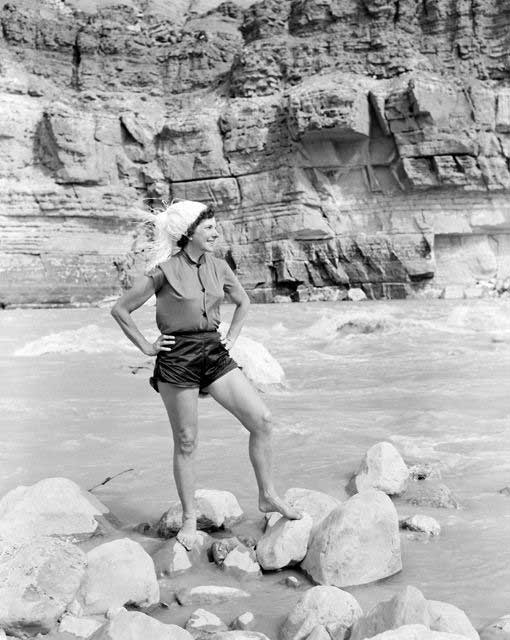

Described in a 1961 Life magazine article as a “new kind of iron-nerve mermaid” Georgie White embraced a new kind of river running that included playful costumes and hats as well as innovative boat designs. Date unknown.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, Special Collections and Archives, Colorado River Plateau Digital Archives. Photo by Josef Muench. Call # NAU.PH.2003.11.4.3.H3828A

By the 1950s, a new era of river rafting had begun. This new era was marked by changes in boat technology and design, the rise of commercial river trips, and the first woman commercial river guide and company owner.

Indeed, Georgie White Clark had the distinction of holding many “firsts” to her record. Georgie was the first woman to swim the Grand Canyon with a single companion. She was the first woman to row a boat through the Grand Canyon. In 1955, she began taking paying customers in “share the expense” trips down the Grand Canyon—this made her the first professional woman outfitter.

She also was the first person to design and use a large rubber raft (early predecessor to today’s modern river craft) capable of taking paying customers, in mass, down the river. She worked to introduce the rapids to any and all paying customers. A major advantage in this goal was the use of an innovative boat design that Georgie crafted. Enterprising on the availability of rubber rafts as army surplus, she devised the “triple rig” or “G rig” with the “G” for Georgie. These rigs were 37 feet long, 27 feet wide and consisted of strapping three large inflatable boats together, then mounting a 10 horsepower outboard motor on the rear of the middle boat. These large boats could safely handle the large flows on the Colorado and carry many more passengers than the standard wooden dory.

Georgie’s river-running career made her witness to and participant in sweeping changes to recreation policies on the Colorado River. In the days ahead, the controversial Glen Canyon Dam would be built (1963), river running would grow into a national sport favored by tourists from New York to Los Angeles, and the National Park Service would begin to regulate this popular sport through permits and user fees.

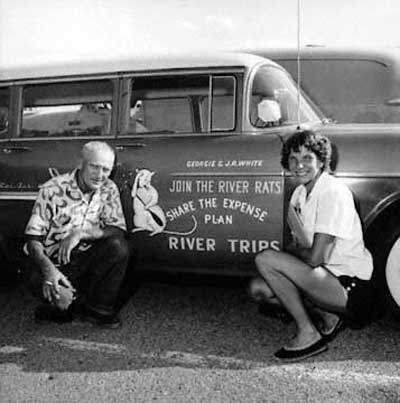

Georgie White helped usher in a new age of river rafting on the Colorado River. Never one to shy from self-publicity, Georgie spent many of her winters touring around the country publicizing the Grand Canyon and her Colorado River trips with films and lectures depicting her river adventures.

A biographer of Georgie White recounts a promotional brochure that Georgie released stating that she was “one of the nation’s foremost woman adventurers, she has done more in a few short years to make this country’s most dangerous rivers and canyons accessible to the average citizen than any other person living, man or woman” (Westwood 1997: 77).

Georgie and her husband help promote commercial river trips through the Grand Canyon on the Colorado River by providing inexpensive no-frills trips. Georgie’s Royal River Rats was the proud moniker for those who had braved the rapids and Georgie’s fresh from the can cooking on the trips. 1955.

Photo: NAU Cline Library, Special Collections and Archives, Colorado River Plateau Digital Archives NAU.PH.96.4.190.218

Although Georgie’s head-strong method of running rapids was controversial from the start, she left a permanent mark on river running. With her large-capacity rubber boats, Georgie could bring more tourists down the river in one trip than any other river runners could in multiple launches on the river. By 1961, Georgie had taken more commercial passengers through the Grand Canyon than anyone else.

Her effect on river use can be seen in the historical counts for river users. In 1955, about 70 users floated down the Colorado River. By 1972, those numbers swelled to over 16,400 people (Westwood 1977: 189). Increasing demands on the river meant more demands on the limited campsites, heavy traffic on the sand beaches, more congestion on the river, and problems with human and kitchen waste on the river.

These challenges spurred the National Park Service to initiate restrictions and a permit system for the river in an effort to lessen these impacts while preserving the scenic qualities of a river trip through one of America’s premier national parks. River trips are still a popular and much sought-after way to see the river, although most who run the river must use the services of a commercial guide and book trips a year in advance.

Written By Yolonda Youngs

References:

- Dellenbaugh, Frederick Samuel. A Canyon Voyage: The Narrative of the Second Powell Expedition. Free e-book from Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20667

- Dellenbaugh, Frederick Samuel. The Romance of the Colorado River. Free e-book from Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4316

- Ghiglieri, Michael P. First Through the Grand Canyon: The Secret Journals and Letters of the 1869 Crew Who Explored the Green and Colorado Rivers, rev ed. Puma Press, 2010.

- Powell, John Wesley. Canyons of the Colorado. Free e-book from Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/8082

- Stevens, Larry. The Colorado River in Grand Canyon: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Natural and Human History. Red Lake Books, 1998.

- Westwood, Richard E. Woman of the River: Georgie White Clark, White-water pioneer. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1997.