Horses may be icons of the American West, but the equine of choice at Grand Canyon has long been its hybrid relative, the mule. These animals combine the sure-footedness of a burro with the larger size and strength of a horse, and have been carrying tourists into the canyon since the late 1800s.

Early prospectors at the Grand Canyon soon realized there was more money to be made from tourism than from mineral deposits. John Hance seems to have been the first to take tourists into the Canyon on mule. On Jan. 1, 1887, he ran an ad in the Flagstaff Arizona Champion offering accommodations on the rim and a mule trip into the gorge. He took tourists down a trail from Grandview Point, about 15 miles east of today’s Grand Canyon Village. He also opened the first hotel at the Canyon’s rim.

In the early part of the 20th Century, wranglers took tourists in horse-drawn buggy rides along the Canyon rim. In those earlier days, the wranglers would string up several mules, lead them to El Tovar and Bright Angel Lodge, put tourists astride and lead them down into the Canyon. In more recent times, tourists meet the wranglers (and their mule for the day) at the corral near the Bright Angel Trailhead.

The daily talk by a mule wrangler, giving the riders instructions for the day, is entertainment in itself. Tourists with no intention of riding the animals often show up just to listen to the wrangle give his spiel.

Today, wranglers lead mule trips down Bright Angel Trail for either overnight stays at Phantom Ranch or for day trips to Plateau Point, where it’s a straight shot down to see the Colorado River. Although the trail these days is open and free for public use that was not always the case. Like so many other early claims at Grand Canyon, Bright Angel Trail sparked competition in the late 1800s.

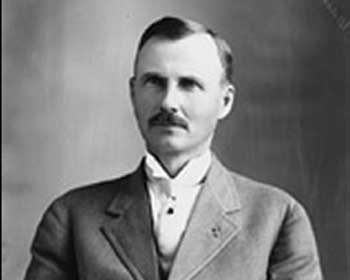

Decades before the Canyon became a National Park, prospectors arrived seeking their fortunes. One of the men who came to Grand Canyon to mine was Ralph Cameron, who arrived from Maine in 1883 and spent the winter of 1889 prospecting near Indian Garden halfway down the gorge.

In 1890 and 1891, Ralph Cameron and two partners widened an old Havasupai Indian trail to Indian Garden. Cameron staked mining claims to about 13,000 acres of Grand Canyon land, including the Bright Angel Trail and Indian Garden areas. As more would-be miners discovered that the true treasure lay in tourism, several groups maneuvered for their share of the business. Cameron’s mining claims gave him control of Bright Angel Trail and from 1903 to 1924, mule riders had to pay Cameron a dollar toll.

To avoid paying the toll, mule trips went down Hermit Trail (west of Bright Angel Trail) to Hermit Camp on the Tonto Plateau from 1913 to 1930.

Not too many years after the mule trips began, a pair of brothers figured out a way to make money photographing the riders. In 1903, Emery and Ellsworth Kolb began taking photographs of the mule riders as they started into the Canyon. Emery Kolb would run four and a half miles down to Indian Gardens to develop the prints, then run back up to have the photos for the tourists as they came back out on the mules.

Among the more than 3 million mule riders that the Kolbs photographed over the decades were Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft; famed journalist Ida M. Tarbell; naturalist John Muir; landscape painter Thomas Moran; and painter/sculptor Frederic Remington.

Tourists can take a seven-hour mule ride to Plateau Point, with a view of the Colorado River, or take an overnight ride to Phantom Ranch at the bottom of Grand Canyon.

The mules are not only put in service to carry tourists. Just about everything that goes in and out of the Canyon to Phantom Ranch travels on the back of a mule. When Fred Harvey Co. built Phantom Ranch in 1922 as an overnight stop for the mule riders, everything except the native stone had to be carried in on mules. Today, supplies to Phantom Ranch are carried in by mules; all trash and U.S. mail loads are carried out by the animals.

The mule and horse barns can be seen across the railroad tracks from Bright Angel Lodge. Those structures, built around 1907, are among the few remain early buildings away from the rim. The blacksmith shop nearby was built around 1908.

In the blacksmith shop, a farrier uses a hammer and anvil to shape metal shoes for the mules’ hooves. In the winter, chunks of tungsten carbide are brazed to the shoes, acting as miniature ice picks to dig into the icy trail for better footing.

Hikers going to Phantom Ranch usually go down South Kaibab Trail and out Bright Angel Trail because there is no water and very little shade on the South Kaibab. The mule trains go the opposite route, taking the less steep Bright Angel Trail down because it is easier on the mules’ legs. They come out the South Kaibab Trail, a faster and more direct route for the mules.

The saddles used by Grand Canyon mules are specially designed and made at the Canyon. They have a flatter underside than a normal horse saddle to better fit the longer, flatter back of a mule and more evenly distribute the rider’s weight. A high cantle at the rear helps support the rider’s back and keeps the rider from sliding backward on the uphill part of the ride. High swells under the saddle horn keep the rider in place for the downhill leg. The horn is useful for slinging a water bottle or for hanging on when the rider feels nervous.

Although some potential riders are afraid of trusting their lives to mules, there’s really no reason for fear. The mules have a great safety record and are chosen for their gentleness and steady nerves. And, they have the right of way on a trail, whether they are walking or resting.

Mules are used for the Canyon trek because they are more efficient than horses and, mule wranglers will tell you, have a smoother gait. Mules are hybrids, a cross between a male burro and female horse. They usually are sterile, but some have reproduced.

Written By Patricia Biggs

References:

- Hughes, J. Donald. In the House of Stone and Light: A Human History of the Grand Canyon, Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1978

- Taylor, Karen L. Grand Canyon’s Long-eared Taxi, Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1992