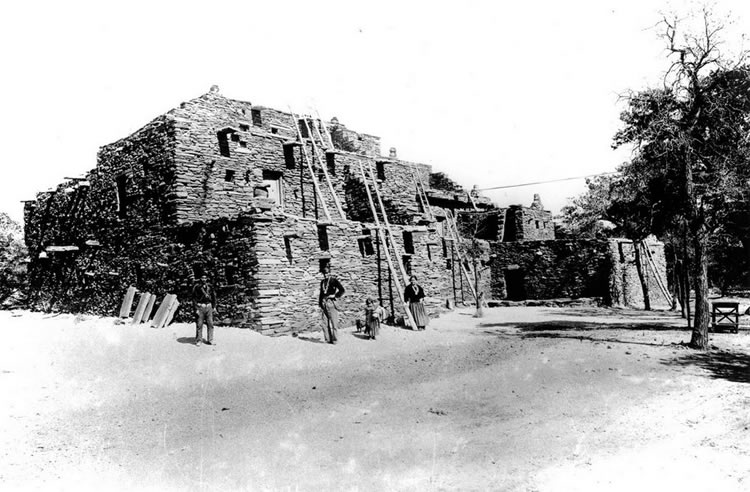

Around the turn of the 19th century, as the United States pushed westward forcing Native American tribes onto reservations, many Americans believed that Native Americans were a “dying race.” They thought that soon Native Americans would vanish due to war, disease, or assimilation into mainstream white American society. Some tourism enterprises, especially in the American Southwest, began encouraging wealthy travelers to come see these tribes while they were still somewhat intact. In particular, the Hopi were a popular tribe to visit, because they were peaceful and, by 19th century standards, were considered more civilized because they lived in permanent pueblos built of multi-level stone structures and created sophisticated arts and crafts. The Hopi and their ancestors typically referred to as Ancestral Puebloans, have inhabited the Grand Canyon area for millennia. To capitalize on this tourist interest, the Santa Fe Railway built Hopi House on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon near its luxurious El Tovar Hotel as a place where visitors could observe Hopi artisans at work and purchase their goods.

Construction of Hopi House finished January 1, 1905, just a few weeks before El Tovar was completed. Unlike El Tovar, Hopi House was designed to blend into the neighboring environment, as it was modeled after Hopi pueblo dwellings at Old Oraibi that used local natural materials such as sandstone and juniper in their construction. While El Tovar catered to upscale tastes, Hopi House represented easterners’ emerging interest in Southwestern Indian arts and crafts, an interest that the Santa Fe Railway and its partner the Fred Harvey Company actively promoted.

Mary Jane Elizabeth Colter designed the structure for the Fred Harvey Company, starting an association with the company and the National Park Service that lasted over 40 years. She helped revolutionize the field of architecture, not only as one of the first women to become prominent in the profession, but also because she created designs that blended into the natural landscape and utilized local building material.

Mostly Hopi workers built the three-story structure out of local stone and adobe masonry just as they might have done for their own homes. The ceilings were thatched with layers of saplings and timbers taken from the nearby forest. These details illustrate the unmistakable interaction between nature and culture. The types of natural resources available determined what types of buildings were feasible, while human creativity shaped the form and function of those natural materials. The result is a building that is both a product of nature and an expression of culture.

Colter made sure that the interior of Hopi House also reflected local Puebloan building styles. Small windows and low ceilings minimized the harsh desert sunlight and lent a cool and cozy feel to the interior. Wall niches, corner fireplaces, and adobe walls contributed to the atmosphere. The building included a Hopi sand painting and ceremonial altar. Chimneys were made from broken pottery jars stacked and mortared together.

For early visitors, Hopi House was a radically new experience because it was part of a new movement in architecture in which designers looked to their own country, even Native American influences, for inspiration instead of to European ideals. Of course, some accommodations to European tastes had to be made; while a true Hopi home would have had an entrance on the roof accessed by a wooden ladder, this structure had a front door for easier tourist access.

When the building opened, the second floor exhibited a collection of old Navajo blankets, which had won the grand prize at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. This display eventually became the Fred Harvey Fine Arts Collection, which included nearly 5000 pieces of Native American art. The Harvey collection toured the United States, including prestigious venues such as the Field Museum in Chicago and the Carnegie Museum in Pennsylvania, as well as international venues such as the Berlin Museum.

Hopi House, then and now, offers a wide range of Native American arts and crafts for sale: pottery and woodcarvings arranged on counters draped in hand-woven Navajo blankets and rugs, baskets hung from peeled-log beams, katsina dolls, ceremonial masks, and woodcarvings illuminated by the suffuse light of the structure’s tiny windows. Hopi murals decorated the stairway walls, and religious artifacts were part of a shrine room.

Many of the Hopi who were involved in the construction of Hopi House lived and worked there afterwards. At least one family lived there for three generations. The multi-story building features many terraces with stone steps and ladders made from tree trunks connecting the rooftops. Each rooftop was the porch for the apartment above it, so that after their day’s work Hopi could relax in the open air and enjoy the company of their fellow artisans and the beautiful vistas of the Grand Canyon. Dean Tillotson, son of former park superintendent Miner Tillotson, remembered that his parents were often invited to the house for dinner, where they would sit on the floor and eat from the communal cooking pot. Nearby, Navajo rug weavers and silversmiths also lived and worked in traditional dwellings called hogans.

The Fred Harvey Company invited Hopi artisans to demonstrate how they made jewelry, pottery, blankets, and other items that would then be put up for sale. In exchange, they received wages and lodging at Hopi House, but they never had any ownership of Hopi House and were rarely allowed to sell their own goods directly to tourists. In the late 1920s the Fred Harvey Company began allowing some Hopi into positions of responsibility in the business. Porter Timeche was hired to demonstrate blanket weaving but was so fond of chatting with visitors that he tried to quit because he could never finish a blanket to sell, at which point he was offered a job as a salesman in the Hopi House gift shop; he later served as a buyer for Fred Harvey concessions at the Grand Canyon. Fred Kabotie, the famed artist who painted the Hopi Snake Legend mural inside Desert View Watchtower, managed the gift shop at Hopi House in the mid-1930s. If they were not working as artisans, Hopi living at Hopi House historically tended to be hired for menial jobs at the canyon, reflecting racial hierarchies that were so commonplace in work and society. Superintendents and other park officials often hired them to help them with housework or other tasks, and the Fred Harvey Company employed them as shoeshine boys, porters, maids, or waitresses.

In the evening, the Hopi (and sometimes Navajo or members of other tribes) sang traditional songs and performed ceremonial dances on the patio of Hopi House. Their dancing every evening at 5:00 became a daily event that both the Santa Fe Railway and the National Park Service promoted in their advertising. The Harvey Company even built a dance platform to accommodate the show around 1930. In this way, Native Americans became almost as much of a tourist attraction as the canyon itself. The Santa Fe Railway and the Fred Harvey Company often used indigenous people in their advertising and promotional materials. However, many Hopi resented having their culture and religion commercialized for display to tourists, and these nightly dances ended in the early 1970s.

Eminent photographer Henry G. Peabody took this photograph circa 1930 of the so-called Hopi Victory Dance or War Dance on the Hopi House dance platform. Note that the performers are dressed in garb characteristic of Plains Indian tribes rather than traditional Hopi styles.

Photo: National Park Service.

From the prominence of Hopi House and the Hopi presence there, many visitors may assume that the Hopi were the only tribe native to the Grand Canyon, but this is far from the truth. In fact, today 12 different tribes are recognized as having cultural ties to the Canyon, and the National Park Service has been working to accommodate the cultural needs of these other groups as well. For more information on other Native American tribes with connections to the Grand Canyon, visit the Native Cultures page.

Hopi House was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987. During a complete renovation in 1995, Hopi consultants participated in the restoration effort and helped ensure that none of the original architectural or design elements were altered.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

References:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. GCA, 2000.

- Anderson, Michael. Along the Rim: A Guide to Grand Canyon’s South Rim from Hermit’s Rest to Desert View. GCA, 2001.

- Barnes, Christine. Hopi House: Celebrating 100 Years. Bend, OR: W.W.West, Inc., 2005.

- Ferguson, T.J. “Ongtupqa Niqw Pisisvayu (Salt Canyon and the Colorado River): The Hopi People and the Grand Canyon.” Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, 1998.

- Grattan, Virginia L. Mary Colter: Builder Upon the Red Earth. Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1992.

- Shields, Kenneth Jr. The Grand Canyon: Native People and Early Visitors. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

- Stampoulos, Linda L. Visiting the Grand Canyon: Views of Early Tourism. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.