The Hopis are one of the oldest living cultures in documented history, with a past stretching back thousands of years. The Hopi trace their ancestry to the Ancient Puebloan and Basketmaker cultures, which built many stone structures and left many artifacts at the Grand Canyon and across the Southwest. For more than 2,000 years, the Hopi have lived in what is today known as the Four Corners region where Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado meet. Their reservation, located in northeastern Arizona, occupies about 1.5 million acres, comprising only a small portion of their traditional lands. Juniper and pinyon pine grow at high elevations on the mesas, while the valley floors are mostly grasslands and the lowest elevations support desert vegetation.

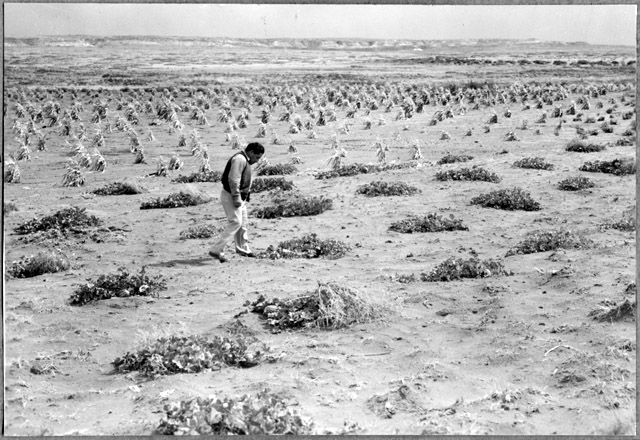

The Hopis live primarily in villages on high, arid mesas that receive only about 10 inches of rain and snow each year. This led them to develop the agricultural practice of dry farming. The Hopi do not plow their fields, but instead build “wind breakers” at intervals in the fields to help retain soil and moisture. They also garden on irrigated terraces along the mesa walls below their villages. They are therefore able to produce corn, beans, squash, melons, and other crops in an unforgiving landscape.

The Hopis began raising livestock introduced by the Spanish who came to the area in the 16th century, especially sheep and cattle, though the size of their herds is limited by the amount of browse and water available. The Hopis also make extensive use of natural resources on their Reservation; for instance, they utilize 134 local plant species for food, grooming, basketry, and housekeeping.

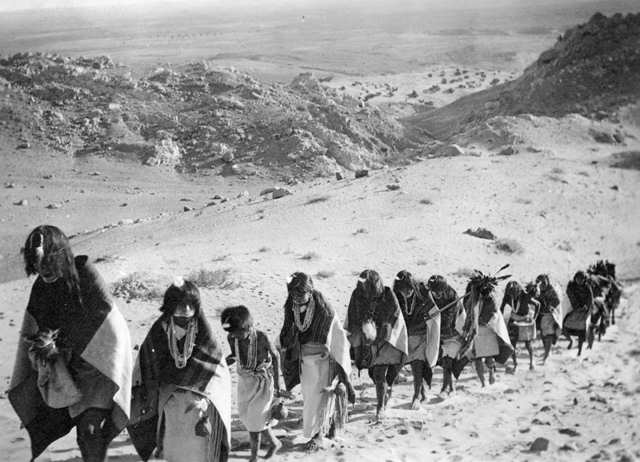

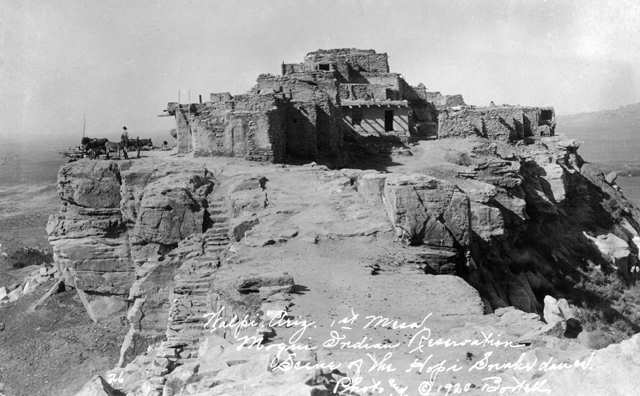

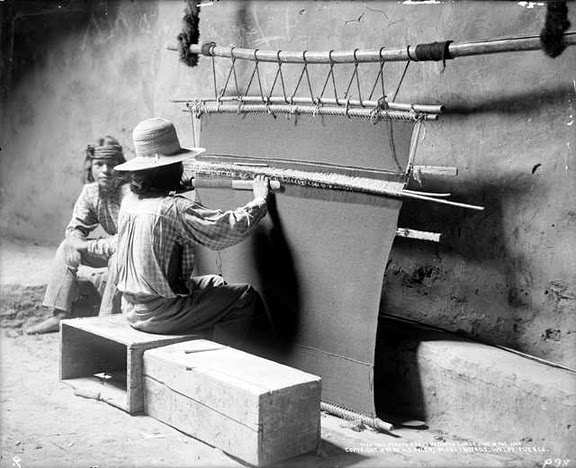

Each of the twelve Hopi villages has an autonomous government, though a tribal council makes laws and oversees business policies for the entire tribe. The village of Old Oraibi on Third Mesa, settled in the 11th Century, is considered the oldest continuously inhabited village in North America. Each village also has a plaza where Hopis perform ceremonial dances passed down through the centuries. Hopi arts and crafts are often influenced by their mesa of origin, with First Mesa famous for pottery, Second Mesa for coiled basketry, and Third Mesa for wicker basketry, weaving, kachina doll carvings and silversmithing.

When migrating tribes entered Hopi territory on the Colorado Plateau, the Hopis retreated to the tops of the mesas and enlisted the help of Tewa Indians from the Rio Grande for protection. The Tewas helped the Hopis drive out the Spanish missionaries during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and eventually became part of the Hopi Tribe. However, today there is still a distinction among the villages, and some Tewas still speak their own native language.

Among the migrating newcomers were the Navajos, semi-nomadic hunters and gatherers who probably traveled south from Canada over many generations along the eastern flank of the Rocky Mountains. Over the centuries, Hopis and Navajos have had a complex relationship, intermingling yet retaining separate identities.

Hopi lands came under control of the U.S. government with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848. When the Navajos returned to the area in 1868 after their forced exile to Bosque Redondo, a treaty with the federal government granted them 3.5 million acres that included their homeland of Canyon de Chelly, about 90 miles east of the Hopi mesas.

Also in the late nineteenth century, Mormon settlers entered the area and once the Santa Fe Railroad arrived towns began springing up uncomfortably near Hopi villages.

The Hopis never fought the cavalry and never signed a treaty. For the most part, they avoided interaction with US government officials. By the late 1800s, US Indian agents wanted to send the Hopi children to boarding schools, but realized they had no jurisdiction because the Hopi villages were not on established Indian reservation land. On December 16, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur established the Hopi Reservation by Executive Order. In a handwritten document, he set an arbitrary boundary between the lines of 110 to 111 degrees longitude west and 35 degrees 30 minutes to 36 degrees 30 minutes latitude north. The 2.5 million acre reservation did not encompass much of their traditional land, important ceremonial shrines, or their village of Moencopi.

From 1868 to 1934, as the Navajo Reservation grew from 3.5 million to 16 million acres, it encircled and diminished the Hopi Reservation. Today, the Hopi Reservation occupies only 1.5 million acres.

The arrival of the Santa Fe Railway in northern Arizona the early 1880s had a profound impact on the Hopi. The Railway and the Fred Harvey Company realized the lucrative tourism potential of the Hopi Reservation, especially since it was so near to the Grand Canyon. Euro Americans had long admired the Hopis for their peaceful attitudes and for their arts and crafts. The company brought Hopis to the tourist facilities it built at the South Rim’s Grand Canyon Village, employing people from the reservation to work at Hopi House and perform dances for visitors, but they also took visitors to the Hopi villages. The companies offered a variety of excursions that took tourists over the Navahopi Road (built in 1924) to the Hopi Reservation, where they could mingle amongst tribal members, shop for souvenirs, and witness cultural events.

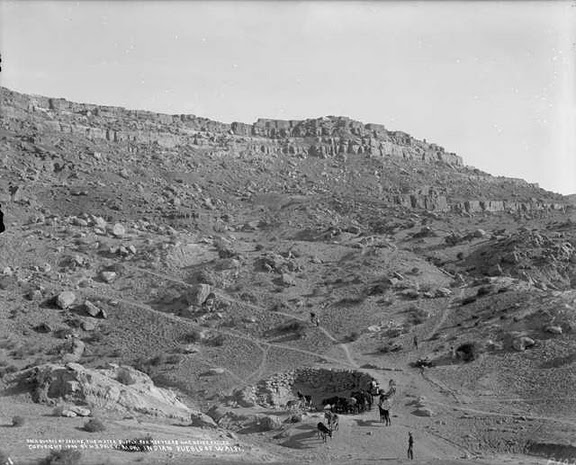

Hopi mesas have relied for centuries on springs that bring water from a large underground reservoir. Here pack mules are being prepared to carry filled water vessels up to the mesas above. Coal mining in recent years has threatened this water source.

Credit: Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library

The Hopis adopted a constitution and created a tribal council in 1936. The federal government disbanded the council in 1943 because it was not enforcing a mandate for livestock reduction to deal with the problem of overgrazing. However, the council was reformed in 1951, mainly in order to create an official governing body to deal with mineral and water rights. Although most of Black Mesa with its large coal deposits was on the Navajo Nation, both tribes shared mineral and water rights there. By 1963 the Hopis had approved oil and gas exploration leases for non-Indian corporations worth several million dollars. In 1966, the Hopi and Navajo tribes signed leases with Peabody Western Coal Company for mineral rights on 64,858 acres of Black Mesa. Peabody also gained rights to pump water from the underlying aquifer. The company had 35-year contracts to supply coal to the 1,580-megawatt Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, and the Navajo Generating Station soon to open near Page, Arizona. In 1970 the Peabody Coal Company began strip mining on Black Mesa. This electricity helps power cities and industry in southern California, Phoenix, Tucson, and Las Vegas. While revenue from these operations brings in much needed money and jobs, the tribes also suffer from air pollution, environmental degradation, and the decline of their precious aquifer and springs caused by the mines and powerplants.

The Hopis still consider themselves primarily farmers, but today almost half of all households have some livestock and most have income from wage labor or arts and crafts sales. The vibrant Hopi culture still draws thousands of tourists to the reservation every year. The Hopis allow visitors to attend some public ceremonies and observe dances, although photographing, sketching, or otherwise recording villages and ceremonies is prohibited. Not all villages are open to the public or allow public viewing of their ceremonies. For information on visiting Hopi land, and for instructions on proper etiquette, visit the web site of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office.

The Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute

One of the most contentious issues among both the Navajos and Hopis has to do with reservation borders and land use. Disputes between the Hopis and Navajos over reservation lands have been going on for decades and continues into the present day. Both tribes are deeply tied to the land, and both have compelling claims to the disputed area.

This dispute stretches back to the creation of the Hopi reservation by President Chester A. Arthur in 1882. The president issued an executive order granting 2.4 million acres “for the use and occupancy of the Moqui (Hopi) and other such Indians as the Secretary of the Interior may see fit to settle thereon.” This vague wording is the basis for the land dispute. There were around 300 Navajos (and Paiutes) living in the area who believed they were the “other such Indians” who were entitled to stay, especially since the Hopi towns were located on their mesas and the Hopis did not use all of the reservation for settlement, only for religious ceremonies. The Hopis argue that the presidential order did not specifically mention the Navajos, and that its intent therefore was to grant the Hopis primary control.

The hostility between the Navajos and Hopis over this land led the Secretary of the Interior in 1891 to designate 300,000 acres of the 2.4 million granted in the 1882 act exclusively to the Hopis. This exclusive Hopi reservation was more than doubled in size in 1943, forcing around 100 Navajo families living in this area to relocate. Still, by 1960 there were about 8,500 Navajo living on land within the 1882 Hopi Reservation boundaries.

The matter was further complicated by a 1934 bill to establish new Navajo Reservation boundaries and eliminate private landholdings within them. This granted about 1 million acres in Arizona to the Navajos. However, it also stated that the lands were set aside for the Navajos and “such other Indians as are already settled thereon,” which included the Hopi village of Moencopi.

In 1962, the Hopi Council sued the Navajo Tribe in Arizona District Court to reinforce the Hopis’ claim on the land allocated exclusively to them in 1943. The court found that each side had valid claims, which did little to appease either side. In 1970 the U.S. government decreed some lands fought over by the Hopis and Navajos as a Joint Use Area. Five years later, a Congressional Act divided the Joint Use Area into exclusive Hopi and Navajo areas, though the tribes must still equally share all subsurface mineral rights.

During the 1960s and 70s, negotiating committees from both tribes met several times to try to resolve their differences, with no success. Finally in 1974 Congress passed the Navajo-Hopi Bill into law. It paid the costs of relocating Navajos currently living on exclusive Hopi lands, and authorized the Secretary of the Interior to sell them BLM land on which to resettle. All non-Hopis living in the exclusive Hopi area were supposed to move by 1986 and vice versa.

Many Navajos eventually moved, but some refused, and as the removal deadline approached, they appealed to Congress for help. In 1980 Congress passed an act that allowed certain Navajos to stay on the land in life estates, despite protests by the Hopis that their legally established rights were being violated.

By 1999, most of the Navajo families who were supposed to relocate had moved, though several still refused to leave. The Hopis and Navajos finally reached a compromise to allow these Navajos to stay on Hopi land by signing a 75 year lease. In 2000, the Navajos and Hopis agreed to a settlement of $29 million for land use and damages on Hopi land that they claimed was caused by Navajo overgrazing. However, there are still lingering issues and tensions on both sides, and many fear the conflict will never be fully resolved.

To learn more about the Hopi, visit their official tribal website at www.hopi-nsn.gov

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke

Suggested Reading:

- Anderson, Michael. Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon Association, 2000.

- Clemmer, Richard. Roads in the Sky: Hopi Culture and History in a Century of Change. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995.

- Dobyns, Henry and Robert Euler. The Hopi People. Phoenix: Indian Tribal Series, 1971.

- Ferguson, T.J. “Ongtupqa Niqw Pisisvayu (Salt Canyon and the Colorado River): The Hopi People and the Grand Canyon.” Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, 1998.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy. Native Peoples of the Southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000.

- Kabotie, Fred and Bill Belknap. Fred Kabotie: Hopi Indian Artist. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona Press, 1977.

- Laird, David. Hopi Bibliography. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1977.

- Malotki, Ekkehart. Hopi-tutuwutsi/Hopi Tales.Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1978.

- Rushforth, Scott and Steadman Upham. A Hopi Social History. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.

- Silas, Anna. Journey to Hopi Land. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2006.