This graphic representation of the Grand Canyon’s geological layers is part of a three-dimensional display in Yavapai Observation Center at Grand Canyon National Park.

Photo taken and modified by Daniel Mayer and posted at Wikimedia.

Key to illustration

6d – Kaibab Limestone

6c – Toroweap Formation

6b – Coconino Sandstone

6a – Hermit Shale

5 – Supai Group

4c – Surprise Canyon Formation

4b – Redwall Limestone

4a – Temple Butte Limestone

3c – Muav Limestone

3b – Bright Angel Shale

3a – Tapeats Sandstone

2 – Grand Canyon Supergroup

1b – Zoroaster Granite

1a – Vishnu Schist

Over the centuries, the Grand Canyon has been many things to many people, such as a shelter for Native American groups, an obstacle to Spanish explorers, and an opportunity for Euro-American miners. However, the Grand Canyon has been an especially important place for the study of geology. Considered one of the seven natural wonders of the world, and the planet’s foremost example of canyon-cutting erosion, geologists over the past century have worked hard to unravel its mysteries. Because the Canyon so clearly lays out many layers of the earth’s crust, geologists from around the world have been drawn here, many making important scientific discoveries and changing the way that people understand our planet, how it was formed and how it continues to change.

A Second Great Age of Discovery was launched in the 19th century from a growing interest in natural history, innovations in geography and biology, and the development of new scientific fields such as geology and anthropology. Science revolutionized our understanding of time, the universe, and human origins. This emphasis on studying the natural world became intertwined with American cultural values such as Manifest Destiny, a belief that it was the divine right and duty of the United States to spread its empire from Atlantic to Pacific. As a result, the U.S. government sent many famous scientific expeditions into the great expanses of the American West, and for a time, the Grand Canyon became one of the most important sources of geological study and understanding in the world. As geologist Clarence Dutton opined in 1882, “It would be difficult to find anywhere else in the world a spot yielding so much subject matter for the contemplation of the geologist; certainly there is none situated in the midst of such dramatic and inspiring surroundings” (quoted in Powell 2005: 4)

In 1858, just 10 years after Mexico ceded to the U.S. its northwestern territories that included the Grand Canyon, physician and scientist John S. Newberry conducted some of the first geologic studies of the park as part of Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives’ exploratory party for the Army Corps of Topographic Engineers. At this time, geology was just beginning to emerge as a field of study, and scientists lacked the vocabulary, methodology, and theory to analyze what they were seeing. Newberry drew the first geologic cross-section, identifying and naming many rock layers, and put forth his belief that erosion by water was responsible for creating the Canyon. This was something of a radical idea, since two centuries ago most European geologists believed the earth was less than ten thousand years old and that all features on the earth’s crust were formed by cataclysmic events such as volcanic eruptions or massive earthquakes.

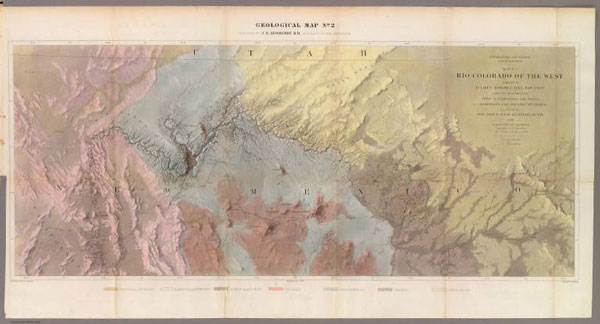

This 1858 hand-colored map, titled “Rio Colorado of the West,” is one of the earliest visual representations of the Grand Canyon area. It was prepared by John Strong Newberry, M.D., a geologist with the expedition led by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives. It was published in 1861 by the U.S. Government Printing Office in the Report Upon the Colorado River of the West, Explored in 1857 and 1858 by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives.

Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

The theory that water erosion formed the Grand Canyon forced geologists and literate members of society into mind-bending speculations about the age of the earth. A water-carved Grand Canyon would have required millions of years of slow, steady erosion. Moreover, Newberry and his successors judged the rock layers through which the Colorado River cut to be much older than the river, orders of magnitude older than the canyon itself. This intellectual revolution embedded the concept of deep time to the modern world and supported other revolutionary ideas such as Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

American scientists were the strongest supporters of the new geology. Scientific observations made at the Grand Canyon helped them overturn older, typically European, ideas about time and geological change. These ideas also brought about a cultural conflict between science and religion that exists even today. Newberry became known as one of the patriarchs of American geology and an important player on the national scientific scene. His student Grove Karl Gilbert first visited the Grand Canyon in 1871-72 and named several features, including the Colorado Plateau and the Redwall Limestone layer within the Canyon. This experience helped lay the foundation for his development of several basic principles of structural geology and geomorphology, so that today Gilbert remains recognized as one of America’s most prominent geologists.

More than anyone else, John Wesley Powell brought the Canyon and the Colorado River to a larger American popular and scientific imagination. As a child Powell had been interested in nature, and largely taught himself biology and geology through observation and collecting specimens.

After the Civil War, Powell became a professor of geology at Illinois Wesleyan University. In May of 1869 Powell and nine men began a 101-day journey down the Colorado River. Based on his observations, Powell theorized that the river existed first, then cut the Grand Canyon as the surrounding Colorado Plateau rose. Two years later, Powell commanded a second expedition that led to widely published maps and scientific findings of the Grand Canyon. In 1875, the federal government published Powell’s Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries. While his descriptions of the Canyon, supplemented with artwork by Thomas Moran, caught the public’s imagination, many still judged implausible his argument that slow, steady erosion created the Grand Canyon.

In 1881, partly because of his field work, Powell became the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, holding that position for the next 13 years. His ideas and experience at the Grand Canyon shaped the field of geology for decades. In particular, his observations from his Colorado River trips led him to establish a system of stream classification that today is considered a basic principle of geomorphology. He also was the first person to unravel one of the geological mysteries of the canyon, the so-called “non-conformities” where entire rock strata are missing or older rock layers appear above younger layers due to tilting and uplifting.

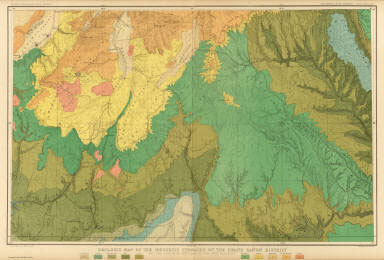

This “Geologic Map of the Mesozoic Terraces of the Grand Canyon District” comes from Clarence Dutton’s Atlas to Accompany the Monograph on the Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District, published by Julius Bien & Co. Lithographers in 1882.

Digital image courtesy of Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Another Civil War veteran also played an important role in understanding the geologic story told by the Grand Canyon. Clarence Dutton worked for the U.S. Geological Survey from 1875-1891, in the meantime publishing his Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, one of the definitive books on the geology of the Canyon. Dutton is known as one of the fathers of seismology, and many scientists regard his work as laying the foundation for modern geology, including the theories of plate tectonics and continental drift, which were based in part on Dutton’s research at the Grand Canyon (Powell 2005: ch. 8). Following Powell’s general hypotheses, Dutton explained how the formation of the Canyon required both the uplifting of the Colorado Plateau and the downcutting of the Colorado River. He elaborated many important principles of erosion and volcanic action that shaped the fantastic landforms of the Canyon. His work therefore contributed to the accepted consensus among geologists by the turn of the century that erosion was an essential force in creating the Canyon landscape. At the same time, he also christened many of the features in the canyon with names inspired by Asian religions or ancient Roman and Greek mythology.

Dutton’s evocative prose helped inspire appreciation of the aesthetic beauty of this unusual landscape, merging scientific understanding with cultural expression (Pyne 1999: 69-71). For instance, in the chapter “The Panorama from Point Sublime” from his Tertiary History, Dutton writes “The Grand Cañon of the Colorado is a great innovation in modern ideas of scenery, and in our conceptions of the grandeur, beauty, and power of nature. As with all great innovations it is not to be comprehended in a day or a week, nor even in a month. It must be dwelt upon and studied, and the study must comprise the slow acquisition of the meaning and spirit of that marvelous scenery which characterizes the Plateau Country, and of which the great chasm is the superlative manifestation.”

Other significant geologists refined the story of Grand Canyon’s deep past over the early 20th Century, including Charles Doolittle Walcott, William Morris Davis, and Francois Matthes. During this time, the Grand Canyon became a symbol of American geology and a medium through which to spread geological knowledge around the world. As Stephen Pyne states, “Science dominated Canyon culture, and geology ruled Canyon science” (Pyne 1999: 110). New generations of geologists continued to come to the Canyon to see what scientific understanding it might reveal. Perhaps most important among these was Edwin “Eddie” McKee. McKee came to the Grand Canyon as a summer intern in 1927, an experience that inspired him to enroll in Cornell University to study geology. Two years later, McKee became the second Chief Naturalist at the park and eventually wrote dozens of texts about the Canyon, including his 1931 Ancient Landscapes of the Grand Canyon Region which went through 30 revised printings until 1985. His discoveries at the Grand Canyon and diagrams he created even today constitute core materials in classes on sedimentology and stratigraphy. He later became the Chair of the Department of Geology at the University of Arizona and served as a research geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey.

Edwin “Eddie” McKee, a geologist who became Chief Naturalist at Grand Canyon Natural Park, wrote many articles and books on Grand Canyon geology. Here he is studying trilobite fossils in the park in 1936.

Photo: NAU.PH.95.48.1107. Barbara and Edwin McKee Collection. Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

By the 1940s, however, the Grand Canyon had become “more museum than laboratory” (Pyne 1999: 132). It was no longer generating paradigm-shifting knowledge as in earlier days, despite the work of important geologists like McKee. Instead, physics and genetics became the cutting edge in science and the Grand Canyon settled into its symbolic status. The Canyon’s scientific significance revived a bit when in the 1950s scientists began reliably dating rocks using radiometric dating techniques, which involve measuring the radioactive decay of radioisotopes in the rocks to calculate when they were formed. However, many of the rocks at Grand Canyon are sedimentary, which means they usually cannot be radiometrically dated. Instead, geologists must use a Geologic Time Scale that estimates the age of rocks based on the worldwide correlation of rock layers, fossils, and other scientific observations.

Not all people accept the geologists’ version of things, however. Miner and early tour guide William Wallace Bass firmly believed that the canyon was the result of a great earthquake that split the earth’s crust, leaving a gash that was later filled by the Colorado River. His son and son-in-law continued to tell the story well into the 20th century at any lectures or guided tours they gave. Some visitors to the Canyon have been overheard speculating that Walt Disney, Steven Spielberg, or some kind of magician must have created it as an optical illusion or special effect. Creationists claim that the Biblical flood during Noah’s time created the Canyon just 4500 years ago.

Most recent scientific studies at the Grand Canyon involve other fields like ecology, hydrology, and atmospheric studies. Yet the Grand Canyon offers geologists a face-to-face look at three of the four major eras of geological time, providing one of the most complete records of geological history anywhere in the world. The Canyon walls encompass a variety of geological features and rock types, with fossils embedded in many of the layers that also provide a look at how life has changed over the nearly two billion years since the foundational Vishnu Schist formed at what is today the basement of the Grand Canyon along the Colorado River. After 150 years the Grand Canyon is still a mystery even to the geologists who study it. As recently as the mid-1970s, scientists identified a new rock layer at the Canyon. Even today, geologists still debate just how old some rock layers are, and when and why the Colorado River began carving the Grand Canyon in the first place, leaving mysteries for future generations of Canyon explorers to ponder over and perhaps solve.

A new outdoor geological history exhibit opened at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in 2010 called the Trail of Time. Extending for several kilometers along the rim trail from the Yavapai Observation Station to Verkamps at Grand Canyon Village is a remarkable educational exhibition on the deep historical origins of the rock formations exposed at Grand Canyon. Wayside information plaques accompanied by cut and polished stone collected from every geological layer of the Canyon’s history are laid out chronologically along the rim trail allowing visitors to walk back in time from the present day at Yavapai Observation Station to several billion years ago at the end of the trail near Verkamps. The Trail of Time was conceived and coordinated by Dr. Karl Karlstrom at the University of New Mexico with the cooperation of the National Park Service. For information and a virtual tour of the trail, visit: http://trailoftime.org/home.html.

Written By Sarah Bohl Gerke and Paul Hirt

References:

- Blakey, Ron and Wayne Ranney. Ancient Landscapes of the Colorado Plateau. Grand Canyon Association, 2008.

- Mathis, Allyson and Carl Bowman. “The Grand Age of Rocks: The Numeric Ages for Rocks Exposed within Grand Canyon.” Available online: http://www.nature.nps.gov/geology/parks/grca/age/index.cfm

- Merten, Gretchen. “Geology in the American Southwest: New Processes, New Theories” in Anderson, Michael, ed. A Gathering of Grand Canyon Historians. Proceedings of the Inaugural Grand Canyon History Symposium, January 2002. Grand Canyon Association, 2005.

- Powell, James Lawrence. Grand Canyon: Solving Earth’s Greatest Puzzle. New York: P.I. Press, 2005.

- Price, L. Greer. An Introduction to Grand Canyon Geology. Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Association, 1999.

- Pyne, Stephen J. How the Canyon Became Grand: A Short History. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Ranney, Wayne. Carving Grand Canyon: Evidence, Theories, and Mystery. Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Association, 2005.

- Sadler, Christa. Life in Stone: Fossils of the Colorado Plateau. Grand Canyon Association, 2005.

- Spamer, Earle E. The Development of Geological Studies in the Grand Canyon. Philadelphia: Department of Malacology, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 1989.

- Stegner, Wallace. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954.

- Worster, Donald. A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Young, Richard A. and Earle E. Spamer. Colorado River: Origin and Evolution; Proceedings of a Symposium Held at Grand Canyon National Park in June 2000. Grand Canyon Association, 2004. Accessible free on-line at: http://www.grandcanyon.org/booksmore/booksmore_epublications.asp